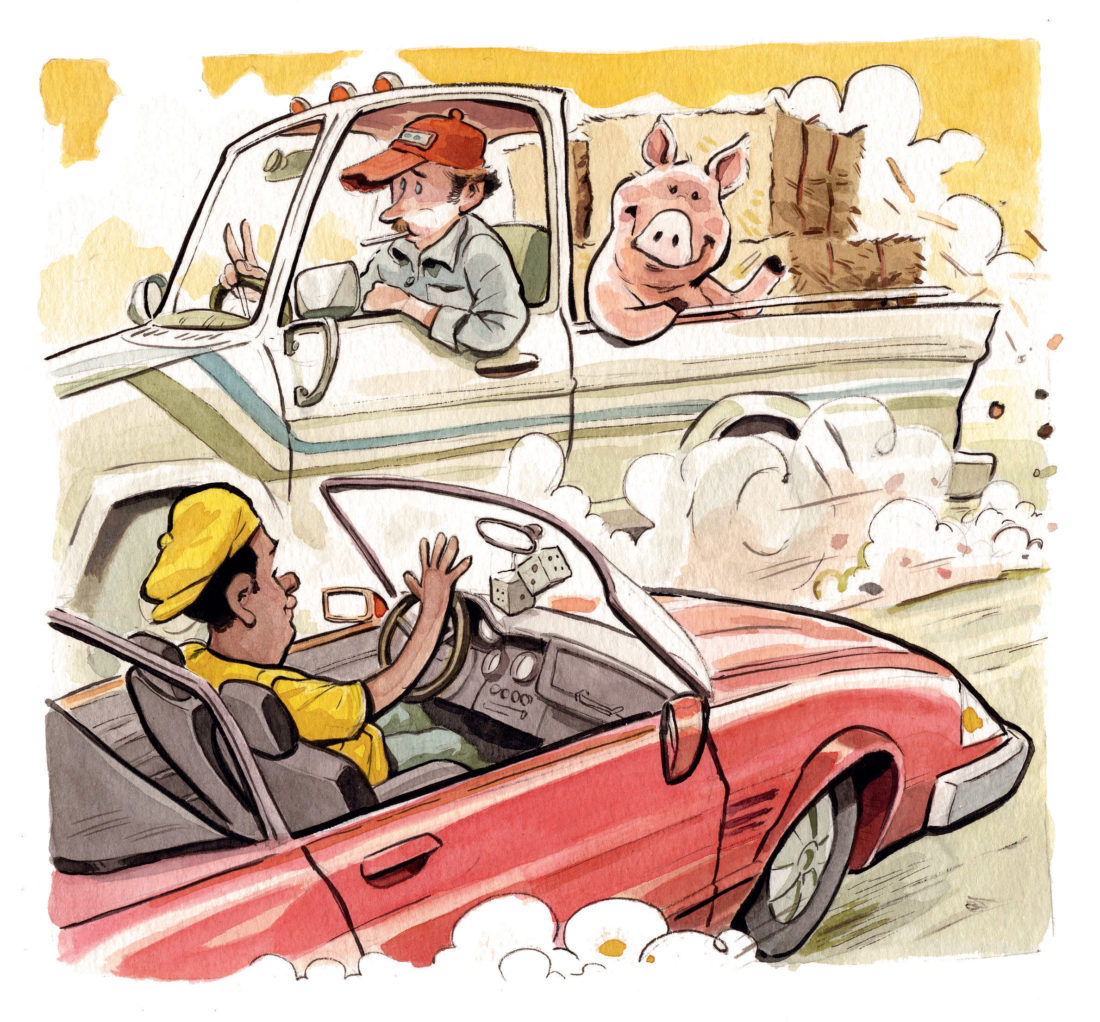

Q. A city friend I brought home was surprised by the way folks wave in the country. Where did this start?

Like good hunting dogs, Southerners have a curlicued agrarian etiquette that has, over generations, seeped into the DNA. So, whether it’s delivered car-to-tractor, pickup-to-car, or pickup-to-pickup, the South’s nearly universal, quirky back-road salutation carries tons of vocabulary. But let’s define the action: We’re talking about locals like you, in a car or pickup, coming at each other on a two-lane blacktop. In August, if it’s dusk, expect the driver’s window to be down and the driver to have assumed the classic left-elbow-taking-the-air/right-hand-on-the-wheel driving posture. At fifty yards and closing, the ritual is, both of you raise a few fingers without your hands, God forbid, leaving your steering wheels. A twilight whoosh, and vaya con Dios. Despite the tiny gesture, the moment can telegraph all manner of text and subtext, from a simple “Safe home, boy” to specific observations or interrogations, as in, “Nice load a hawgs,” or “Didja git them soybeans in?” A salutation of this fraternal order reaches back in the millennia to Greek battlefield etiquette—it’s about the recognition of an ally, a laying down of arms. It carries the profound message that the world may be a place of siege, but between countrymen, no battle is foreseen.

Q. Making a Southern party playlist. Is there an unsung artist I should include?

With a tip of the hat and an apology to Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart for the mangling, all party music mixes should bewitch, bother, and bewilder. As your guests power up with martinis, there’s a grand, sly surprise to be found in Tuscaloosa, Alabama’s own Dinah Washington. Born Ruth Lee Jones in 1924, she landed her first steady club gig as a teenager in Chicago. But her 1948 take on Fats Waller’s “Ain’t Misbehavin’” kicked off a blazing run of top-ten R&B hits, including “Baby Get Lost,” “Trouble in Mind,” and “What a Diff’rence a Day Makes.” Her dulcet mezzo-soprano carried great power, but she could also twist the knife in

a ballad or deliver the hot sauce on an up-tempo romp with heart-stopping finesse. She busted genres, recording blues, jazz, and pop, along with R&B; she even covered Hank Williams’s “Cold, Cold Heart.” She lived as hard as she sang, running through seven husbands and dying, at age thirty-nine, from a toxic mix of barbiturates. Washington made the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame because she could climb inside the skin of any song and ring down the most sublime forms of hurt. She’ll do that for your playlist.

Q. New to the South, but one thing seems clear: Women run the show around here—right?

Correct! We’ll put a rush on your permanent-resident visa. That the South is run by its women is a narrative that’s been under construction since Bienville wrote King Louis XIV from Mobile to send some women over, and fast, to bring his troops to heel. Louis’s good ship Le Pélican arrived at Dauphin Island with the first twenty-three women in 1704, so there’s been plenty of time to hone the subtle and not-so-subtle means of control. But let’s fast-forward three hundred years so you can ask me why the hell I’m pulling off the road to negotiate with a man to bring me two heavy-vinyl white tents, fifteen tables, and 150 chairs? Noon sharp? Tomorrow? Not to mention the half-dozen parking valets I’m stealing from the restaurant down the hill? Or the iceman’s bafflement when I call him with the ice calculation? All of it architected, so to speak, by my sainted South Alabama mother for a party. And she’s not alone. Generally, the women of the South can put men running—it’s not their main work, but an awe-inspiring and at times terrifying skill set. With the exception of the putatively determined-by-men SEC football schedule, no Southern gathering is without the female guiding hand. Know it. And love that we’re better for it.