Wondering: Home more and acreage aplenty, so wouldn’t it be fun to bring in some pigs and chickens?

While we admire the impulse to set up the Southern homestead circa 1925, with the chickens out back and the hogs quartered in Great-granddaddy’s barn, could you please prune your vision of agrarian bliss to one species? Farming’s most deceptive axiom is that any animal you allegedly “own” requires you to work for it, not the other way around. As future employers go, chickens are nominally the beginner’s easier choice. Your goal is to create a setup that will give you a break from your 24/7 imitation of Sisyphus, say in February, when a freak gale drops the temp to ten below and you have to wonder whether the ventilation you cut in the coop last summer will cause the combs and wattles on your Barred Rocks and Buff Orpingtons to freeze, or whether you need to gather some one-bys, your hammer, saw, sawhorse, insulation, and a pocketful of sixpenny nails before heading out at 3:00 a.m. to warm those birds up. But before we get into what kind of long underwear you prefer, let me back up: Do you have enough permethrin on hand for that roost-mite infestation, or are you betting diatomaceous earth and wood ash will do the trick? Is the flock pecking that one hen to death because the timer broke on your coop light and you took a week to notice, or is she looking ragged because she’s molting? Get the picture? It’s why they call it animal husbandry—you’re married to each and every one of ’em, and you’re in it for better and for worse.

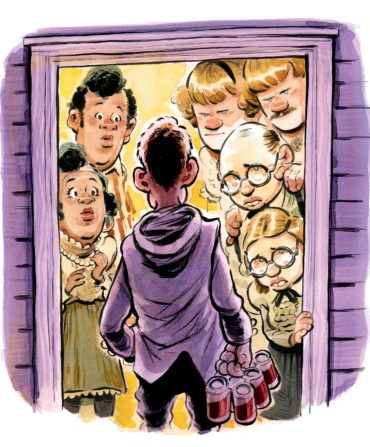

Is issuing zero invitations for the holidays, not even to Aunt Mabel, whom we always have up from the coast, the best tactic this year?

The year carries many long tons of mortal freight, hurting us in every endeavor, those crucial to the fight against SARS-CoV-2, such as PPE for frontline health-care workers, and in the tangential features of social life, such as concerts and dinners. As huge swaths of the South led the nation in infection rates this past summer, it seemed clear that the spike would rough up T’giving/Xmas 2020. Southerners are more instinctive hosts than guests, so that, as Dr. Fauci admirably keeps hammering home, it’s a long war in which we’re obliged to err on the side of prudence, dialing back the most gregarious telephone-book weddings and just-us family dos alike. Your example extends to every family. Show the Aunt Mabels of the South that you care in every other possible way, sending along some good books and fine chocolates. And bombard them with a more sustaining level of care, an element of contact that often falls by the wayside at a boisterous holiday table, namely, with a few plainspoken words from the heart.

I love Louis Armstrong. But, artistically speaking, there’s the creator phase, then the pop phase, right?

Armstrong’s brilliant profile in American music might seem divided: The blistering burst of songwriting and musical creativity of the 1925 to 1928 Chicago sessions with his Hot Five and Hot Seven doesn’t quite square with the full-blown “entertainer” racking up performances of “Mack the Knife” and “What a Wonderful World” on stages from Paris to Vegas to Accra. Don’t belittle the later Armstrong; he could make it all swing. His “Hello, Dolly!” shoved the Beatles from the top of the chart in 1964. Then sixty-two, he remains the oldest musician to have a number one. Armstrong was protean, and never stopped being that, in his deft musical assembly of the grand African American narrative traditions of his native New Orleans, his diamond-hard transposition of those skills into the soaring jazz solo as we know it, and his unapologetic vocal innovations, not the least of them his popularization of scat. Any single such accomplishment would make him a founding father of the American songbook; Armstrong did all three to the end of his life. His embouchure was so ferocious and his ability to hit a high C so athletic that his lip would bleed down his shirt. He pared the calluses with a razor, as a boxer’s cutman would cut a swollen eyelid. Louis Armstrong was beyond tough, and he had the innate grace to make it all seem easy.

Have a burning question? Email editorial@gardenandgun.com