In the second semester of 1965, I was visiting writer in residence at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. My chief duty consisted of teaching a narrative writing course and making myself available to any student who might choose to drop in at the office I shared with the great Jessie Rehder. When the class commenced in early January, I made a brief and hardly strenuous assignment for our second meeting — I forget the subject — and was fairly amazed by the response: maybe five students out of fifteen brought me literally nothing. When I expressed my surprise, and trusted these refusals would not occur again, one of the empty-handed students said, more or less, “Relax, Mr. Price, this is Chapel Hill, not Duke. We’re a little more laid back over here.”

Brownie Harris

I was not amused, but I kept my own counsel; and as January lagged on through one of the grim winters we expected four decades ago, more and more of the students conceded that I was unfortunately but irredeemably from Duke — those eight miles away that often seemed like a thousand — and their papers grew steadily regular. Given the fact that, today, I’ve taught nearly fifty years — and some three thousand students — it’s remarkable that I recall at least two stories from that one course, both autobiographical and eloquently powerful.

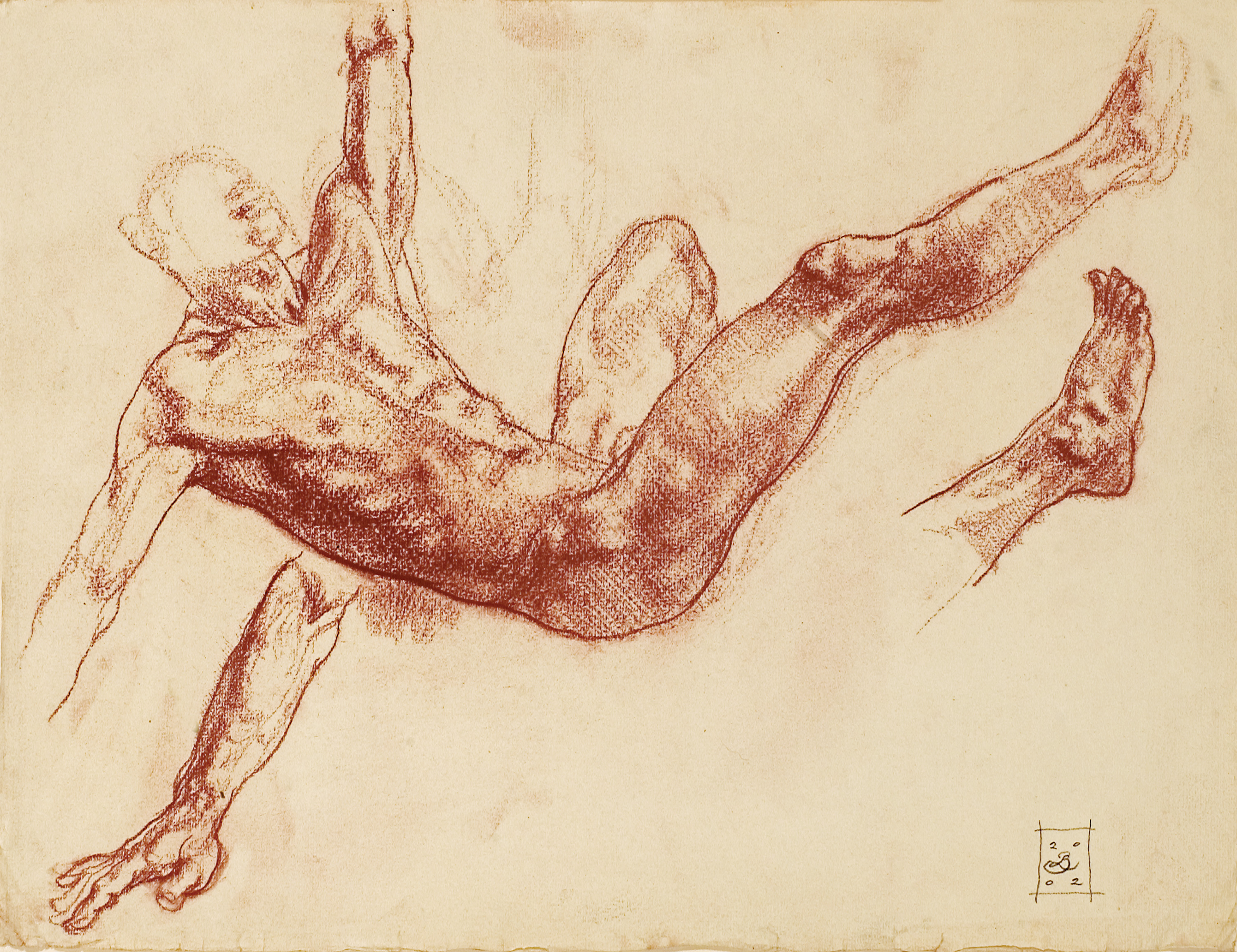

Art Courtesy of Ann Long Fine Art

Neither of those highly original stories, however, was by a young man who sat near the back and seldom spoke, though his striking face and eyes were plainly not missing a word. When I’d ask for his response to the story of the day, he tended to blush before speaking up memorably. His name was Ben Long; he’d grown up in Statesville, and though he never told me that year, I’d eventually learn of his gifted and fascinating grandfather who painted large pictures with biblical imagery at least as arresting as that of any short story we discussed in our class. It’s odd to record, more than forty years later, that I don’t recall the writing Ben submitted in that course (but what did all the other stories do to his growing imagination?).

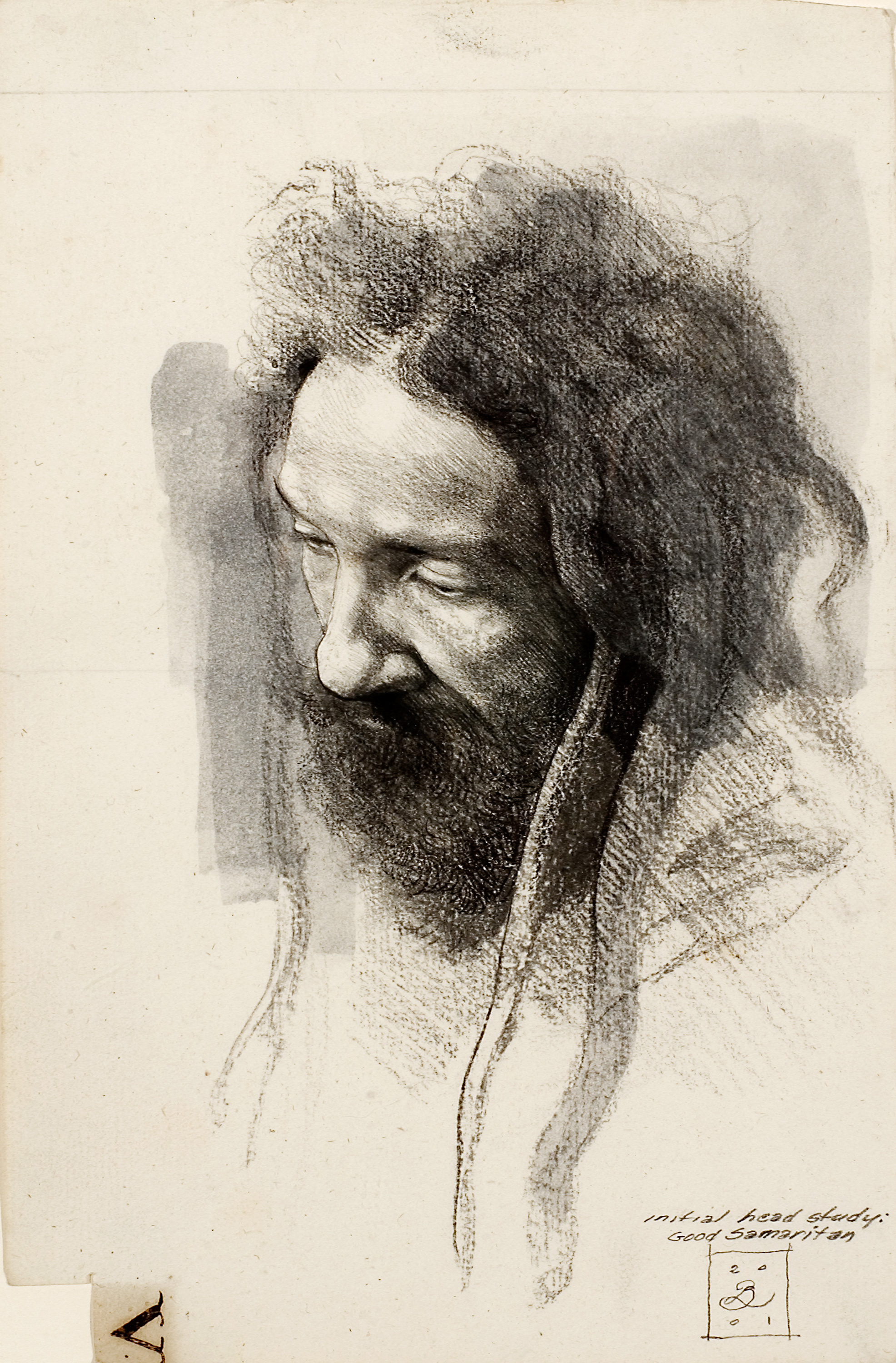

This all-but-silent boy … had laid down page after page of drawings of a calmly assured and already enormous skill.

What I do remember, very clearly, is the fact that when I invited the class to my home — where dozens of paintings and drawings were hung about all the available walls — I noticed that Ben was immediately engaged in an activity that almost no student — and almost no other visitor of any sort — had performed. He was intently moving slowly from one picture to the next and consuming them with his large eyes. He said nothing, then and there; but when I returned to my Chapel Hill office a day or so later, Ben turned up with a light tap on the doorframe. Was I free to talk a little while? I told him I was free to talk as long as he liked; so he crossed the door sill, and as he advanced toward the empty chair by my desk, I noticed that he was carrying a spiral bound sketchbook in his left hand. What was I about to see?

Art Courtesy of Ann Long Fine Art

First, though, he wanted to talk about my house and its wide array of pictures. What was the history of my interest in art? Did I myself draw and paint? How did I acquire most of my pictures? And on and on. I told him the truth — that from about the age of five or six onward, I’d been obsessed with the idea of reproducing with crayons, pencil, and, eventually, oil paints, objects I loved in the external world. By the time I was in the sixth grade, I’d very much decided on art as a lifelong career; but as I aged a little more — and saw more and more pictures by famous professional artists — I began to suspect that my own gifts were insufficient. If I pursued a career in art, I was likely to be nothing better than a competent copyist. I began then to buy the pictures of other and far better painters. Luckily, the realization of my insufficiency coincided with my having superb English teachers in the eighth and eleventh grades — women who liked my drawings but liked my prose and poetry better. Always eager for praise, by the time I left high school I’d turned toward writing as my lifetime’s work.

Brownie Harris

By then I couldn’t resist asking Ben about his sketchbook. Was there anything in it that he’d let me see? Of course he blushed, but he handed me the pad and I slowly leafed through it. My clear memory still is chiefly one of pleased amazement. This all-but-silent boy from the Carolina foothills had recently laid down page after page of drawings — mainly portrait drawings — of a calmly assured and already enormous skill. I’ve never been a teacher who withholds praise when praise has been earned, though I’ve always tried not to insult the obviously talented student with over-praise (six years before I taught Ben, I’d taught Anne Tyler). Once more, then, I had the big privilege of telling an extraordinarily young artist — and telling him at length — that he was dead right to be forging on with his new main hope (he’d also thought of being a poet). He told me that he was hoping to visit Andrew Wyeth in the coming summer of ’65, and maybe to volunteer his services as the man who swept the studio floor — any free service if only he could silently inhabit the same working space as a painter he much admired.

Photo: Charles Gilbert Kapsner

Ben Long working on the Resurrection fresco at St. Peter’s Episcopal Church.

We parted happily that afternoon; the semester moved onward toward its close in May, and my excellent covey of remarkable students scattered like starlings; and — almost as always — I lost all of them (but for one who became a steady friend). I’ve never tried to pursue gifted students. If they wish to maintain contact with me, all the better; I’ll return the serve. But I’m fearful of pressing my own hopes for them in some unwanted fashion: So very few artistically talented students — writers, painters, whatever — wind up actually accepting the immensely hard labor and potentially devastating solitude of a life in the arts, ferocious mistresses that all of them are.

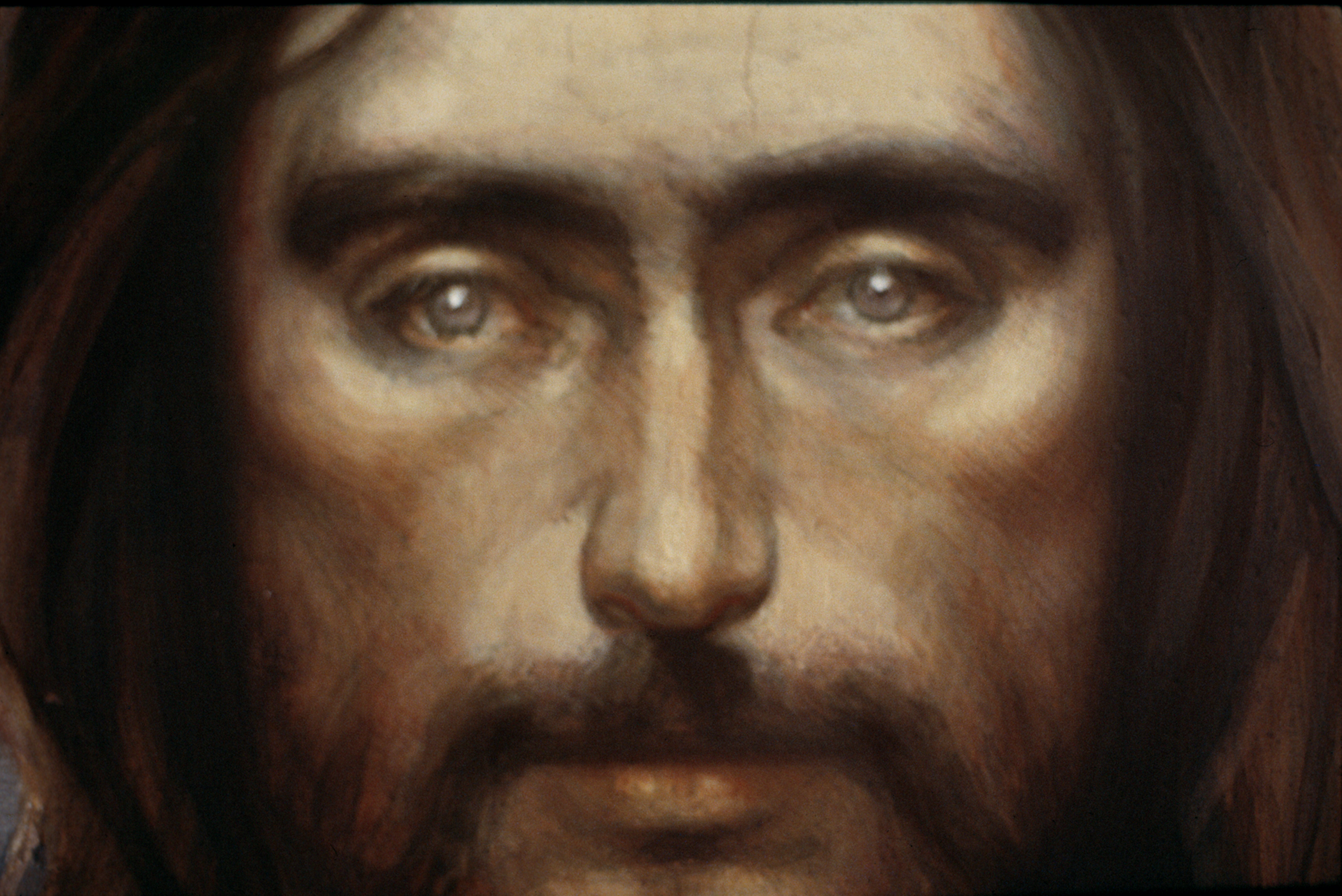

Photo: Charles Gilbert Kapsner

Detail of the resurrected Christ.

I lost all touch with young Ben Long for maybe ten years. I didn’t know of his early marriage, his years in Vietnam, his return to the States, and then Italy, to plunge head foremost into serious study of drawing and painting. Then, in the early 1970s, a Duke colleague of mine sent me a postcard from the Abbey of Montecassino, in Italy. The handwritten message said, in effect, “Your old student Ben Long is working here and sends you good wishes.” Only then did I realize that the color image on the other side of the card was a reproduction of one of the frescoes Ben had added to a newly restored building that had been destroyed by Allied bombing in 1944. How could I have failed to detect — even in a postcard’s cramped size and untrue colors — the hand I’d admired nearly ten years earlier in Chapel Hill?

Photo: Art Courtesy of Ann Long Fine Art

Girl in a Red Hat (Katie), oil on panel

Despite my failure, in the early 1980s I slowly rediscovered Benjamin Long. We met again — in Blowing Rock and Glendale Springs — and have gone on meeting, far too seldom but always memorably, ever since. We even, in the mid ‘80s, spent many dozen hours intently together as Ben drew and painted me. Those hours deepened not only my admiration for all he can do — and his unnerving comprehension of my face — but also, I think, our mutual affection, the unique bonds that only fellow artists seem able to establish: bonds of unstinting admiration, yes, but also of the will to help one another in a kind of work at least as lonely as the prayerful life of a desert monk.

Art Courtesy of Ann Long Fine Art

I haven’t seen Ben now for maybe four years, but writing these few words about him makes me long to hear his fine baritone voice and join him in another main skill we share: the gift of laughter, and of finding life itself mainly comic — however tragic, too — wherever our solitary trades may lead us the moment we part.

Art Courtesy of Ann Long Fine Art