One Thursday night a couple of decades ago, I stopped with a good friend at a restaurant in the panhandle of Florida. That panhandle holds places that, culturally, seem kin to some parts of southern Georgia. The owner wrestled alligators on the side, and there was live music out back. The mostly retired people in attendance sat in folding chairs beneath the roof of a large half-finished cinder-block garage. I wanted to write about that place, those people, but I couldn’t get my nouns and verbs around the norms and customs of that panhandle pocket and its citizens. I didn’t know it right.

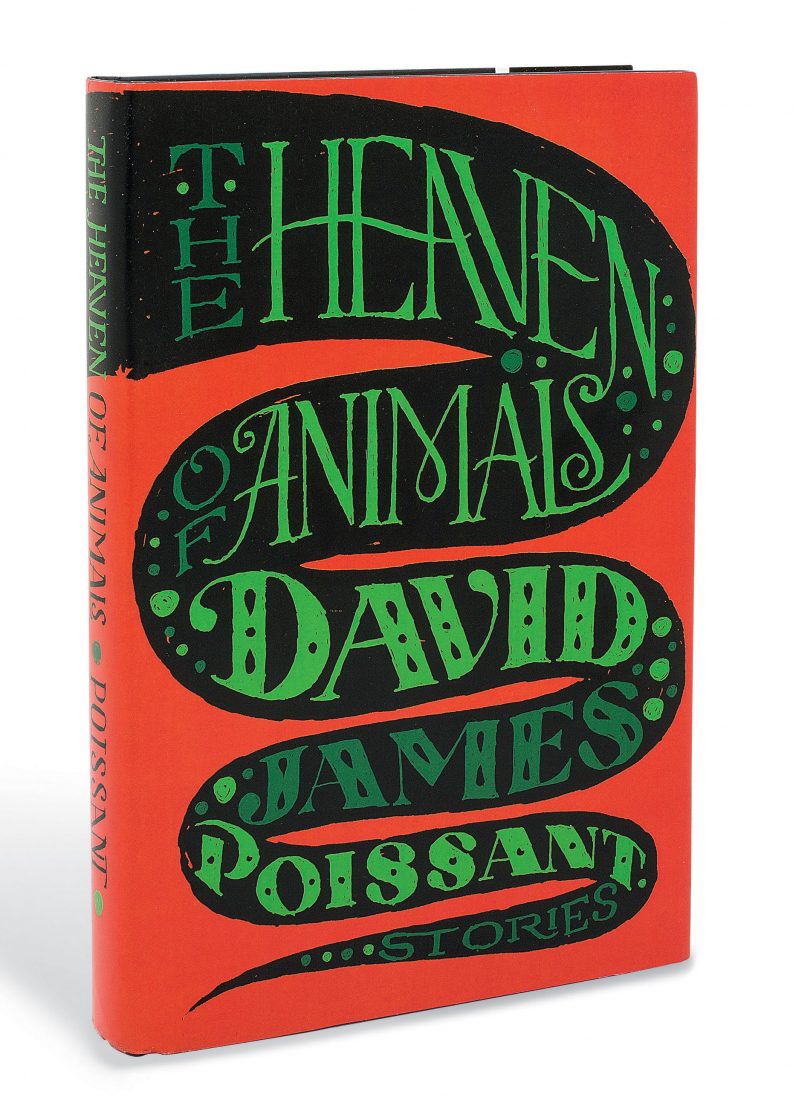

David James Poissant, in his first book, a collection of stories, The Heaven of Animals, writes about these people so well—many are from Florida and Georgia—that you feel you’ve gained access to their world through his gift of fiction writing.

A great big gift. So big that it stretches the short story form a bit; he turns typical short story writing pitfalls into strengths—lengthy flashbacks, two stories made into one. He gets away with using two points of view (a perspective usually reserved for novels), with writing a story that is bigger in the middle than at the end, with bringing in information that in another writer’s hands would feel way too late, with writing the right facts coming from the “wrong” person.

The stories travel across the South and beyond—to Kentucky, Arizona, California. We find and follow out-of-luck people, some in the same dire straits you’ve watched yourself navigate in nightmares.

“Lizard Man,” the first story, is told from inside the head of a maladjusted, dysfunctional, angry, flawed, fearful father. You can move among William Faulkner, Harry Crews, and Flannery O’Connor to find the muscle that is in this story (and many of the others here), and among Eudora Welty, Lee Smith, and Jill McCorkle for the tenderness. A masterful piece of short fiction, “Lizard Man” will show you how much in common you might have with a person you could never admire.

And therein lies a great strength of this collection: Though many of the characters are not like us readers one bit (some are), Poissant shows us how much alike we all are—as fathers, mothers, friends, children, liars, and lovers—no matter our pedigree. “Refund” and “The Geometry of Despair” will resonate with young parents worried about their children before as well as after they arrive, and “Me and James Dean” speaks to the bonds between people and pets. Poissant allows his art to become moral in the best way: It takes us to new places where we find that we must, in order to be kind to our own selves, throttle judgment.

The last story in the book, “The Heaven of Animals,” is a continuation of the first, “Lizard Man.” The structure of this book thus becomes a new form—a novella split by stories. As to the animals of the title, they pop up throughout: a stubborn twelve-foot alligator, an imaginary wolf, an unpredictable herd of bison, all serving as counterpoints to our “human condition.” Poissant’s use of animals in his stories also reminded me of the naturalism of his literary uncles and aunts—those Southern writers with agrarian backgrounds.

You’ll find plenty of humor in these pages, wonderful metaphors (“like a drawer flung open to an intimacy of spoons”), and a clarity that makes for a smooth ride. Above all plots, a human chord will be heard. And Poissant can do the seemingly impossible: render a wordless state of mind that’s very much like a dream, something you’ve felt but never said. One example:

“Maybe I’ll catch one of your swim meets sometime,” he said.

“Maybe,” she said.

They nodded the way people do when they agree to something both know will never happen and, in agreeing, know the other knows.

The writer as magician.

Poissant is young—already pulling live rabbits from a tall hat. And I hear a novel is on the way.

Look out.

Garden & Gun has affiliate partnerships and may receive a portion of sales when a reader clicks to buy a product. All products are independently selected by the G&G editorial team.