Only in the South can the past be woven so passionately into the present. That salient bit of time bending inhabits every form of expression, be it food, architecture, business, music, art, or politics. It’s what Faulkner meant in Requiem for a Nun with his much-lauded epigram: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Which is why, one crisp late-fall Saturday night many years back, it seemed I had something like an eternity to mull the many profound whorls in the sediments of Southern time that had brought me to my—I hoped temporary—stay in the Ardmore, Alabama, jail.

Jail, or the close prospect of it, has a way of focusing the mind on immediate options and on larger cosmic issues at once. Specifically, I waited for Ardmore’s jolly desk sergeant, beleaguered with a raft of other Saturday-night miscreants, to be briefed by my arresting officers so he could decide whether my offense—the possession of one six-pack of (unopened) beer—merited an invitation to enjoy a night in his facilities, or whether the many bigger fish he had to fry in his rowdy little town might just allow me some bootlegger’s version of a hall pass.

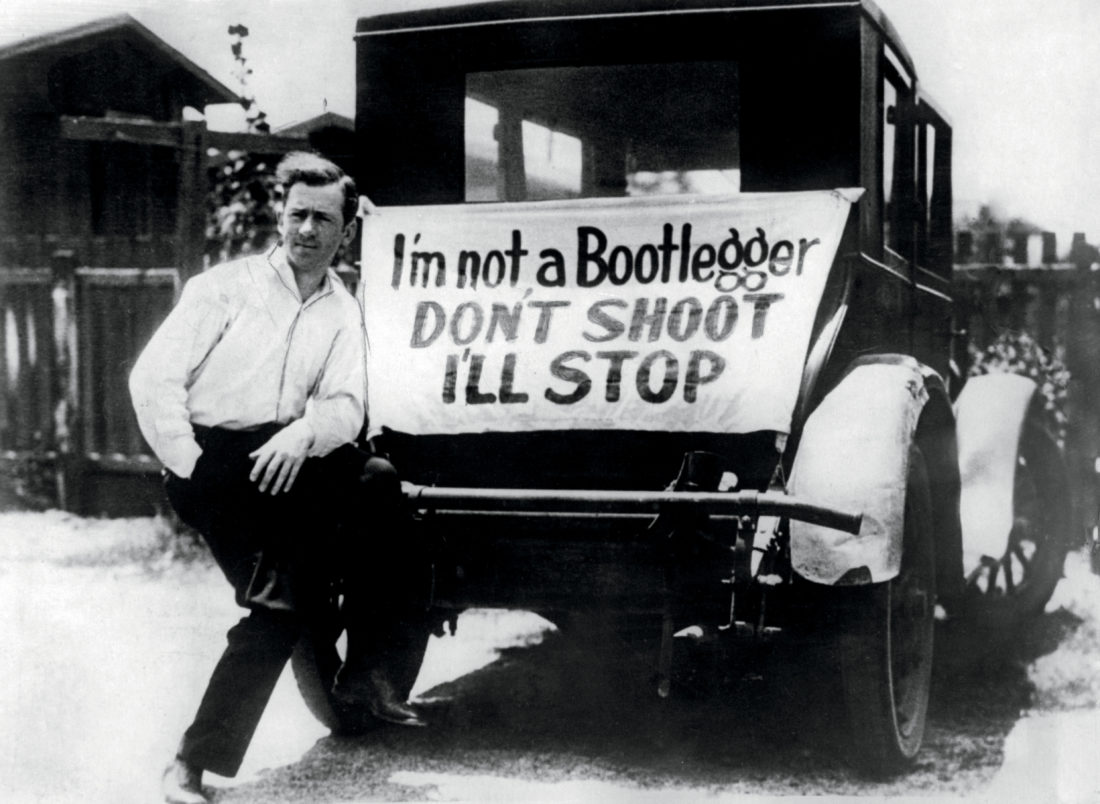

My bench in the anteroom to the holding cells provided an excellent vantage point from which to ponder the South’s apparently endless love of Prohibition. Technically the Eighteenth Amendment was repealed in 1933, but in the Deep South, in evocation of our wise Nobel laureate Faulkner, that disastrous piece of law got snapped right back up and re-legislated in a mad patchwork fashion across Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, Texas, and even in the South’s reputed no-holds-barred repository of “sin,” a.k.a. Louisiana.

The backstory: My home county, Limestone, in which the main part of Ardmore lies, is dry and has been for the almost nine decades since Prohibition’s repeal. Though in Alabama, the legal implementation of Prohibition in 1920 came less as a shock and more as a comfort and confirmation: Fifty-eight of the state’s sixty-seven counties had already voted themselves bone-dry by 1908. That means whole generations have been brought up in a liquor-running paradox. No matter how law-abiding a citizen might be, if he or she drank, that person lived on the far side of the law.

But in Ardmore, there is a sharper legal cutting blade at work, because the Alabama-Tennessee state line splits Main Street. Bluntly put, the liquor laws in Ardmore are those of the two-faced god Janus. The northern sister city of Ardmore, Tennessee, is wet. Hence the package store on the north side of Main, where I bought my “illegal” six-pack, and the police on the south side of Main, to whose custody I was remanded. In the language of our more gifted Limestone County hellfire-and-brimstone preachers, north of Ardmore’s Main Street lay eternal damnation. South of Main lay a possibility of salvation. But if you sinned north of Main in Ardmore, Tennessee, and then strayed back a few feet south to Ardmore, Alabama, your transgression might well be absolved with the help of the police.

For the record, my takedown went like this: As I opened the back door of my car to put the beer (in its regulation unmarked brown paper sack) behind the seat, a pair of beat patrolmen, clearly in the habit of fishing this productive Saturday-night revenue stream from their stakeout, nabbed me. One of them reached around me to confiscate the six, and in an eyeblink I was in the back of their patrol car en route to my booking.

Did I mention I was on a date? To spare her any embarrassment—not at the circumstance, an ordinary one in Ardmore, but at having dated me—I’ll keep the detail sparse. Suffice it to say she was whip smart and quite lovely, and she waited with a champion’s grit in our car as the police took me in. She had invited me up to a dance in Pulaski, Tennessee, where her grandmother lived in a fine old high-ceilinged Victorian perched on one of the hills. We had no notion of getting drunk; we just wanted a couple of sociable beers to take to the dance and had stopped in Ardmore. My bad. I made a mental note to drive much farther into Tennessee before buying beer the next time.

That was a bootlegger’s thought, and a natural one at the time. Because: As they do in any dry county from Texas to Georgia, Limestone County’s dry ordinances had wholly deformed the social matrix. Alabamians grew up watching parents and friends’ parents bootleg. We learned the architecture of the trade early.

It was a classic Newtonian reaction, equal and opposite to the law. First, the dry law created a busy little community of professional bootleggers. For decades, they tried their level best to supply my hometown of Athens and Limestone County, and they gave the municipal police and county sheriff’s deputies a great chase. But whether it was the people with the big icebox on Coleman Hill, with whom I had no dealings, or the well-known David Kirby, who between bouts of jail did supply my brothers, me, and many other thirsty Athenians, none of the bootleggers could handle the market volume. Our mother’s dinner and cocktail parties alone would have broken the supply chain.

Instead, having to drive great distances to get alcohol became a feature of ordinary civic life. This is a genteel way of saying that, in the largely dry Alabama counties of the Tennessee River valley, the twin crimes of possessing and hauling were made universal. Each drinking-age member of a family—including many scions of staunch dry-law supporters—became what I’ll call a “citizen bootlegger.” Doing the run entered the vocabulary. We all memorized the county roads through the cotton and the various cuts and feints. Naturally, the sheriff’s deputies had long known every turn in those roads, and better than we.

In Limestone County, the political geography confronting a citizen bootlegger was, and is, key to one’s encounter with the law. The direction of your drive mattered. From Athens, back then, you could drive the eighteen miles to (wet) Madison County, Alabama, home of Huntsville’s NASA installation at the Marshall Space Flight Center, which made for a sophisticated municipal voter base. It was a thirty-six-mile round trip. Or, you could drive nineteen miles north to Ardmore to the state line, a thirty-eight-mile round trip.

From a citizen bootlegger’s perspective, the real problem with buying in Ardmore was not that the police would watch from across the street as you loaded up, though that would happen. Your larger problem was that, since you bought the alcohol in Tennessee, you had paid no Alabama state tax on that alcohol, which—depending on what you’d been caught with—launched your legal liability into the stratosphere. In Alabama today, transporting more than five gallons of alcohol is, still, a felony punishable by a year in jail—a risk citizen bootleggers routinely ignore. Home from college one summer, my brothers and I cohosted a hundred-strong party for which we hauled at least twice that, not counting the beer and wine.

Bootlegging culture and the weaponly tapestry of dry jurisdictions engineered one other highly fraught habit in us. To be able to visit a restaurant and order a drink with dinner or to have a beer at a bar as we watched a football game, we drove the bootlegging routes to Madison County or to Tennessee. In short, Alabama’s wet-dry legal tangle made getting, having, and drinking alcohol a furtive, de facto criminal enterprise from the get-go. The road was made a place for alcohol. You had to drive to get it, and if you drank it on the spot, you still had to drive back, a deadly endeavor for people of any age, but most egregiously and tragically so for the young. We all had close friends and former classmates get hurt or die out on the county roads.

The politics of bootlegging in Athens underwent a slightly hobbled sea change toward reasonableness in the early aughts, when the town approved the legal sale of alcoholic beverages. As a small college town and a bedroom community to the academic and industrial center of Huntsville, Athens had slowly been secularized beyond its cotton-town roots. Despite the change creating a pleasant several-hundred-thousand-dollar bulge in the tax base that goes to schools and city services, referenda to repeal the decision still happen every few years; the latest failed in 2015. Outside the city limits, Limestone County remains dry.

In the end, the Ardmore desk sergeant found a measure of mercy and let me off with a fine. Relieved of our beer and most every penny of my cash, but relieved in a larger way to have gotten some of the evening back, we even made the dance in Pulaski. By the fire at my date’s grandmother’s house, the last thing I wanted to think about was the Ardmore jail, but it was still with us. Safe in her grandmother’s living room, I remember thinking how lucky we were to have made it out of the scramble. But outside the windows, just south of town, Saturday night on the state line still raged and the mighty current of Prohibition rolled on, the hordes of thirsty youth, the sheriff’s men, the run down the two-lane blacktop. The game had been going on for so long it had become part of us. Deep down, we both knew it never should have been that way.