If the priests were correct for once and I were to ever go blind, if my world went to shadow and black and I couldn’t see a solitary thing, I submit for your consideration that I could still drive from Yazoo City to Greenwood, Mississippi. I know this journey cold. Surely you’ve got a road like that. A drive you can make without thinking, each turn and straight carefully wrapped and stored in the closets of your memory. I’ve ridden this road hundreds of times. The first was when I was just weeks old. The last time was a week ago.

The first left took me down a wooded hill away from my uncle Will’s house, where he lay in a bed dying. His room overlooked those same woods. I’d come here to say goodbye and in his familiar house, where we’d gathered so many times, I couldn’t shake the strangeness of his shrinking world. His entire life now consisted of one room. He was never again to walk down his hall, past his fireplace, through his bright yellow kitchen and into his pantry, where so many memorable meals began. There was something beautiful about this winnowing. His and my aunt Becky’s room was the center of the home and their family. It felt like the house itself was alive and in triage, shutting down unnecessary extremities.

Uncle Will loved that Delta drive, too, often taking it instead of the quicker route down the highway. Every mile held another memory, so in a metaphysical way, his moving along the road was the story of his life. That he liked that road was an unsurprising but new fact about him, and the realization that there were things still to learn, and with time rushing away, things that I would never learn, left me feeling unmoored. Aunt Becky told me that detail with a smile, in an accent suggesting a fragility that I can testify does not exist. A crisis reveals her backbone and strength. She is unbreakable and was in charge of these precious days. There’s a saying my dad had about his mother-in-law that applies to my aunt, too: When Becky says it’s Easter, it’s time to start dying your eggs.

The next right pointed me toward the Yazoo Country Club, which always evokes a half-remembered story about my grandfather being made to feel less than by polite society folks and how his superior golf game was the way a country boy told city people to go to hell.

I took a right on U.S. 49.

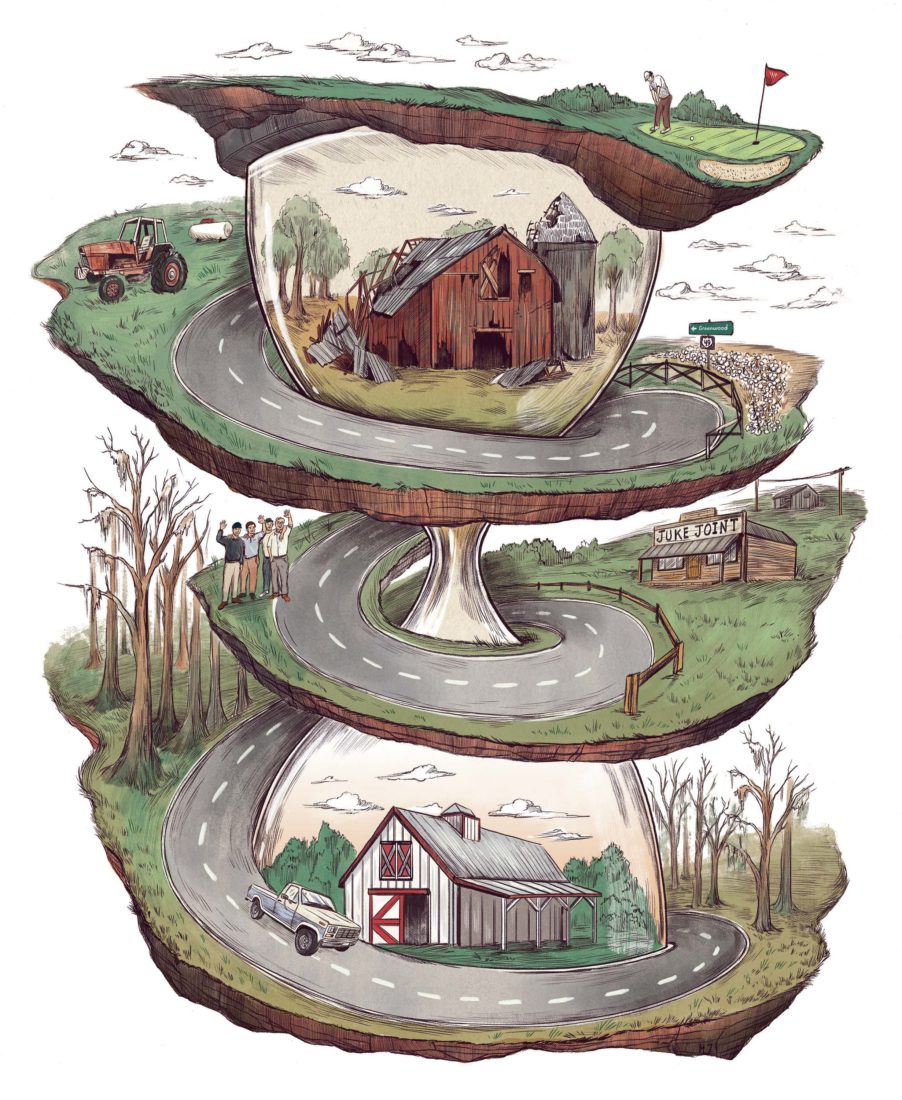

The road turned country fast. Little farm towns like Renshaw. Abandoned cotton gins. New metal barns erected next to collapsing rotten wooden ones—a juxtaposition that toys with the structure of time and reality; a philosopher’s dream, as if to say: You might be new and shiny now, but one day you will be like me. American Ozymandias. Look on my works and despair, rushing past the Eden Midway Road. A big sweeping loop at Bee Lake, and the juke joint in Thornton, where I imagined the guitars moaning and ringing like lone and level sands. Maybe they just have a stereo now. A closed country store that once served bologna and hoop cheese sandwiches. Where did all those people go? Who raises money for them with a counter jar whenever their kids need an operation down in Jackson?

I tried to find a spot on the left side of the road that my dad always talked about, but I couldn’t find the landmark. Old propane tanks, I think. Or maybe a power facility? Without that visual trigger, the story floated just beyond my ability to recall. I could see the shore but couldn’t reach it. A panic set in. My dad used to narrate this stretch of road with stories of his childhood and young adulthood. I remember my mom and I laughing and rolling our eyes as he told the same story at the same place, a story I now couldn’t remember. It was about some old football game, I think? Maybe baseball. My whole job as a son is to remember his stories so he doesn’t die again and again. What a betrayal then to lose this part of his life that I’d been entrusted to remember. Did it happen in Thornton? Mileston? I looked out at the skeletal trees of Delta winter thick on the banks of bayous and creeks, like even the land knew there was a great man dying behind me. Uncle Will is my dad’s older brother.

There were four boys altogether, and they grew up on a farm outside Bentonia: Frazier, Will, Walter, and Michael. Now only Will and Michael are left. Yesterday was Michael’s seventy-second birthday, and Will is dying in his bedroom. The hospice nurses said a month. Then a week. My cousin, Will’s son, told me to come quick. I sat in the wooden chair by his bed and wept. I told him I understood I’d never see him again, and how much I appreciated the love he’d shown me, and how I hoped he’d tell my daddy hello in heaven. He gripped my hand and said, “Thank you for caring for me,” and with those words in my head, I walked out of the room and let his grandson take my place in the chair. Minutes were as precious then as fine sandy loam. People were generous with each other in that unspoken way.

Everything else at the house was a blur, and now I was on this familiar road, looking at the barren trees and the silver blanket of winter coming down. I didn’t turn on the radio and tried for miles to remember. The roadside played its own music. Tchula snuck up fast, the Triple S grocery buzzing with pickup truck crossroads energy across the highway from a prehistoric-looking cypress swamp, the same color as the collapsing houses up and down the road. I thought about my uncle Michael, who would soon be the only Thompson brother left. A terrible responsibility will be his alone to shoulder. No one will share his memories of his parents and of their parents, of life on that farm in the years they called it home—both a place and a time endangered and vulnerable. The unwinding road felt familiar but also foreign, like a thing breaking into pieces and slipping through my fingers. There are Indian mounds all around this road, and it occurred to me that we don’t know a single thing about the men and women buried in them. We don’t even know what language they spoke, or their hopes, dreams, and fears. The land shows they existed but nothing more. The Northern Irish poet Seamus Heaney wrote, “History says, Don’t hope,” and this is what he meant, I think. That memory is a half-hearted matador wave at unstoppable forces we can barely name, much less understand.

A sign outside Greenwood had a faded, worn cotton plant on it. That felt about right. As a child, I’d want to go to a fast-food chain when we got here, but my dad always insisted we stop at Malouf’s deli. Now I understand why. I don’t remember what we ordered, but when we finished, we’d make the turn toward Clarksdale, where we lived when I was growing up. Now I go the other way and head to Oxford (where I live with my wife and daughters), through Teoc, near the overgrown grave of the Choctaw chief who signed the treaty that gave this dirt to the United States. Mississippi is made from the broken pieces of things that used to be, by memories preserved and vanished, by myths and traumas, and by the roads and roadsides where all those things live.

I got back home just as a winter storm started, and as the land turned cold and bleak, my uncle Will died. He left this world just after midnight, fourteen hours after I said goodbye, surrounded by his children and by their children, who prayed with him and sang him hymns. His body lay in a bed that looks out over a forest of trees, which looks out over a highway, which follows a railroad that follows an old forest path, which follows rivers and streams and bayous. I wondered what his spirit saw when it rose out of this place. Did he only stare upward in wonder at a kingdom where nothing and no one is ever lost to time? Or maybe, just once, he looked over his shoulder to see for a final time the dominion of frail humans who are forever trying and failing to hold safe the people and places we love.