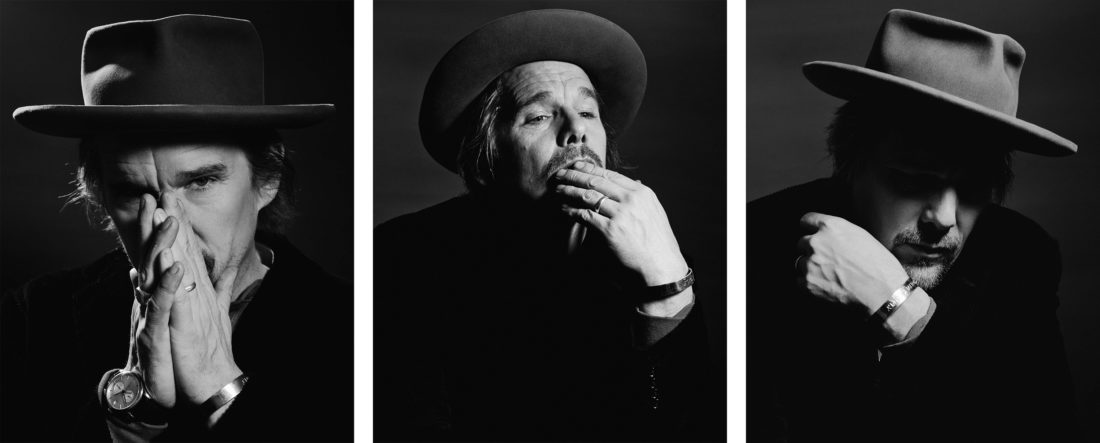

If you stand for the Lord, the Lord will stand for you!” So bellows the abolitionist John Brown, as played by the Texas native Ethan Hawke in his starring role in the spirited Showtime miniseries The Good Lord Bird, which begins airing October 4. Hawke, the forty-nine-year-old four-time Oscar nominee, also executive produced the miniseries—which is based on the 2013 National Book Award–winning novel by James McBride—with, among others, his wife, Ryan, and Jason Blum (Get Out).

The Good Lord Bird tells the story of Brown—played in a winning, full-throated manner by Hawke—as told by a fictional, formerly enslaved child named Onion. Freed by Brown, Onion joins him and his crew of abolitionists during the Bleeding Kansas confrontations in the late 1850s and follows him to the famous raid on the Harpers Ferry armory, after which Brown was captured, tried, and hanged, becoming the first U.S. citizen to be executed for treason. The tale is funny, thought-provoking, and, of course, very much pertinent to our historical moment. Here, Hawke shares his thoughts on why Brown’s story resonates, the role of an artist, and how the South stays with him in everything he does.

What a time for this miniseries to air.

It’s been intense. As I was doing research on John Brown, I came across a letter he wrote just before he was hanged. Someone had written him and told him he was sorry he was going to be hanged. And Brown wrote back, telling the man that it takes between six and nine minutes to die from hanging, and that he would do more for the abolitionist cause in those final minutes than he did in his entire life. If you think about that in the light of what happened to George Floyd and what the final minutes of Floyd’s life have meant, it sends shivers down your spine. We’re still reacting to events that happened so long ago. It’s still going on. We filmed this in Virginia, and I stayed in Richmond and would walk along Monument Avenue and see the statues of Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, and I was getting into character and thinking, What would John Brown want to do to these statues?

The statue situation is so interesting.

I’m a lover of history and prone to want our history to be respected, but it really is fascinating to see what and who we have chosen to honor. On the set of The Good Lord Bird, we wanted to get into the period mindset, so Christy Coleman, who ran the American Civil War Museum, came and spoke to us. Someone asked her about the Confederate statues, and she had a fascinating answer. She said that after the Civil War, the South suffered a great and terrible loss, not just lives and money, but a loss of pride and self-esteem, and that these statues represent a society caught in the first stage of grief, which is denial. This is where I think John Brown comes in. When I was growing up, my parents divorced, and I went back and forth between homes. My mom was in Vermont, where they taught kids about John Brown, and my dad was in Texas, where they didn’t. I found it really confusing. This country hasn’t really looked at the truth of the Civil War and why it happened, and it’s why race issues are on the front pages now.

Onion has a great line about Brown: “Whatever he believed, he believed. It didn’t matter to him whether it was really true or not.” Brown is such a complicated figure, messianic or demonic, depending upon whom you ask, who believed that “the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood,” as he wrote in his final letter.

I had a driver who took me to the set. One day he kind of whispered to me: “You’re not doing a positive picture of John Brown, are you?” I said, “I don’t know. Why do you ask?” And in truth, McBride’s portrait of Brown is very human, nuanced, and complicated, not positive or negative. The driver then said, “Brown was a terrorist. He killed people.” Well, Lee did, too, and so did all of those guys on Monument Avenue in what was, essentially, an insurrection against the United States. The genius of McBride’s book is that he knows that individuals are not to blame for what happened 150 years ago. He’s not pointing fingers. But we’re still caught in the web created by these old crimes. They’re in our country’s DNA. And [the hurts they caused] need to be healed. The trouble with telling stories about slavery is it can make people feel guilty and upset, and those two things usually turn to anger and rage, so many people turn away. McBride looks at it with wit and love and makes you laugh. It’s like the story of John Brown as told by Richard Pryor and Redd Foxx. And when you start laughing, you see humanness in everyone—the enslaved, Frederick Douglass, J. E. B. Stuart, Brown. McBride asked that we cast people we liked in real life as the racists in the show because, he said, if the racists have horns, then the Black suffering isn’t real. Some think John Brown was insane, but he believed that a society that supported the enslavement of humans was insane, that the disease was violence, and the cure was going to be violence, and that he’d be that violence.

How did you prepare for the role?

I visited Brown’s grave site, I read everything I could—biographies and his letters. But I had to remind myself that I wasn’t playing John Brown, I was playing McBride’s John Brown, which is Brown as viewed by a fourteen-year-old boy. In the book, McBride manages to walk a razor’s edge and honor the reality while making you laugh. He makes fun of everybody. No one is spared. It’s Twain-esque. He pulls it off through the voice of Onion, who just wants to live, and will be a slave or a freedom fighter, or wear a dress to do so, and who, in the end, figures out who he really is, finding something worth fighting and dying for.

Along with your eighty-three movie and television acting credits, you’re a stage director and actor, a screenwriter and movie director, a documentarian and producer. You’re also a musician, and you have published three novels and one graphic novel. What drives you?

I’m not sure I know. I realized during quarantine that there are some positive manifestations of being a restless soul and there are some negative ones. I’ve had time to ask myself, What are you running away from? But I’ve always been doing two things at once since I started acting at age fourteen, like writing a book while filming a movie, or preparing to play Macbeth while acting in an action movie. One domino would always hit another. It makes me happy, I guess.

What does being an artist mean to you?

It’s like a family Thanksgiving. Some people cook, some make the fire, and somebody has to sit at the table and say, “Hey, guys, what are you thinking about, what do you want to talk about?” Someone has to push the conversation. An artist’s job is to make time fun and valuable on a deeper level, to be entertaining and thought-provoking. I see it as part of our collective mental health. A society that’s rich with ideas and able to handle complicated conversations and open dialogue is a healthy one.

You were born in Texas but moved away as a child. Is the South still a part of you?

It never leaves you. I moved around a lot, living with my mom all over the place. But my dad was always in Texas. I went there in the summers, which were filled with heat and love and joy. When I sit down to write, it always ends up being about Texas. It’s where my imagination lives. My first two novels were about Texas, to some degree. Blaze [Hawke’s film about the Austin musician Blaze Foley] was about Texas. I’ve done films in South Carolina and Louisiana and Virginia. My friendship with [the director and Texan] Richard Linklater is rooted in a love of the South. And, to put it simply, I don’t think you ever get those black-eyed peas and cornbread out of your system.