At the end of a muddy lane on Johns Island, South Carolina, past a crashed airplane in the vines, Leigh Magar is kneeling inside a broken-down horse trailer. She has just set down a cane—adorned with rusted cowbells to scare off snakes—and is dipping a cotton bag into a large, pungent vat of fermenting indigo, which she keeps in the trailer to contain the odor, a stench something like a dirty wet dog. When Magar removes the bag, it’s green and dripping dye, then slowly—like a photograph developing—turns blue before our eyes.

Hanging it on a fence to dry, she says, “I gotta get some things sent out to Brooklyn.”

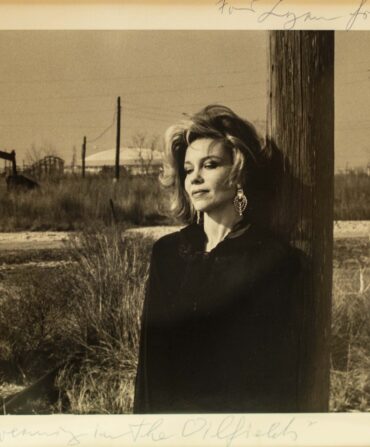

Photo: Olivia Rae James

Magar in a dress and apron from her line

The globe’s most cosmopolitan zip codes have long been interested in dispatches from the singular world of Leigh Magar. For twenty years she made her name as a celebrated milliner, her hats seen from the pages of Vogue to the windows of Barneys. But three years ago Magar sold her Charleston atelier and moved with her husband to a house hidden within the Spanish-moss-draped oaks on nearby Johns Island.

“We wanted to make life easier,” Magar says. “So we decided to sell everything.”

Soon, though, she was making life complicated again. Inspired by the story of Eliza Lucas Pinckney, who introduced indigo to South Carolina in the 1700s, Magar began to grow indigo at her new home. Once one of South Carolina’s foremost plantation cash crops, second only to rice in the years before the Revolutionary War, natural indigo has long been abandoned in favor of modern dyeing techniques. Magar is determined to bring it back. She now uses the plant to dye an array of small-batch handmade garments and home goods that make up her Madame Magar line.

“The process is an act of intuition,” Magar says of extracting indigo dye, which comes from the leaf, not the flower, and is brought out via a method of fermentation that Magar says resembles the making of yogurt. “It’s a lost art, which is part of why I do it.”

Photo: Olivia Rae James

Magic Brew

A batch of Magar’s fresh-leaf indigo dye

Magar’s dye recipes vary—“It’s been years of me developing my own stew,” she says—from batches of freshly picked leaves that develop over a couple of days to vats that ferment for months at a time. She also employs other foraged pigments in her work, such as dandelion, hickory nuts, and black walnuts, which steep in a rainbow of jars on the shelves of her studio. Like a scientist, she tests different dyes to see how they react to swatches of cotton and silk; indigo yields a spectrum from pale sapphire to midnight blue, black walnut makes “the darkest dye of the natural world,” loquat a rich peachy hue, camellia a yellow ocher.

Magar draws additional inspiration from other Lowcountry traditions, like Gullah rag quilting, which she recently worked into the design of a jacket made from indigo-dyed cotton swatches sewn together in a bouquet of cloth.

In addition to making everything from shift dresses to tea towels, Magar leads workshops and produces textile art. Most of her items are available in limited runs through pop-up shops, in boutiques in Charleston and New York, and on her website. Whatever she makes, though, Magar’s designs are elegant and pared down because the process demands everything remain small-scale and one-of-a-kind. This is exactly how she likes it. “I’m just going to make things that I love,” she says, “and utilize nature.”