Drawn to bright colors, beer drinkers, deodorant, perfume, and sweat, mosquitoes are one of the South’s more unpleasant facts of life. But a fascinating new book by Timothy C. Winegard, a professor of history and political science at Colorado Mesa University, reveals just how much the little beasts have influenced the world—to the tune of claiming some 52 billion human lives. The Mosquito: A Human History of Our Deadliest Predator traces the defeat of armies, birth of nations, and shaping of culture all at the hand—or wings—of the mosquito. And as you might expect, the South, in all its humid, sticky glory, makes a number of appearances. From playing key roles in major conflicts to fueling our coffee habit, here are five ways the mosquito has left an indelible mark on the region.

1. Mosquitoes gave chrysanthemums a bad reputation in the South

Before people gave chrysanthemums as tokens of love, they mashed them up and used them as insecticide, a practice that dates back to ancient China. That’s because the flowers contain pyrethrins, chemicals that attack the nervous systems of insects, including mosquitoes. While in the Northern United States, chrysanthemums generally enjoyed a reputation as positive symbols of vitality and joy, their link to the mosquito connected them to death and disease in the South, specifically in the mosquito-ridden city of New Orleans, where they were often used to decorate the gravestones of yellow fever and malaria victims until the early twentieth century.

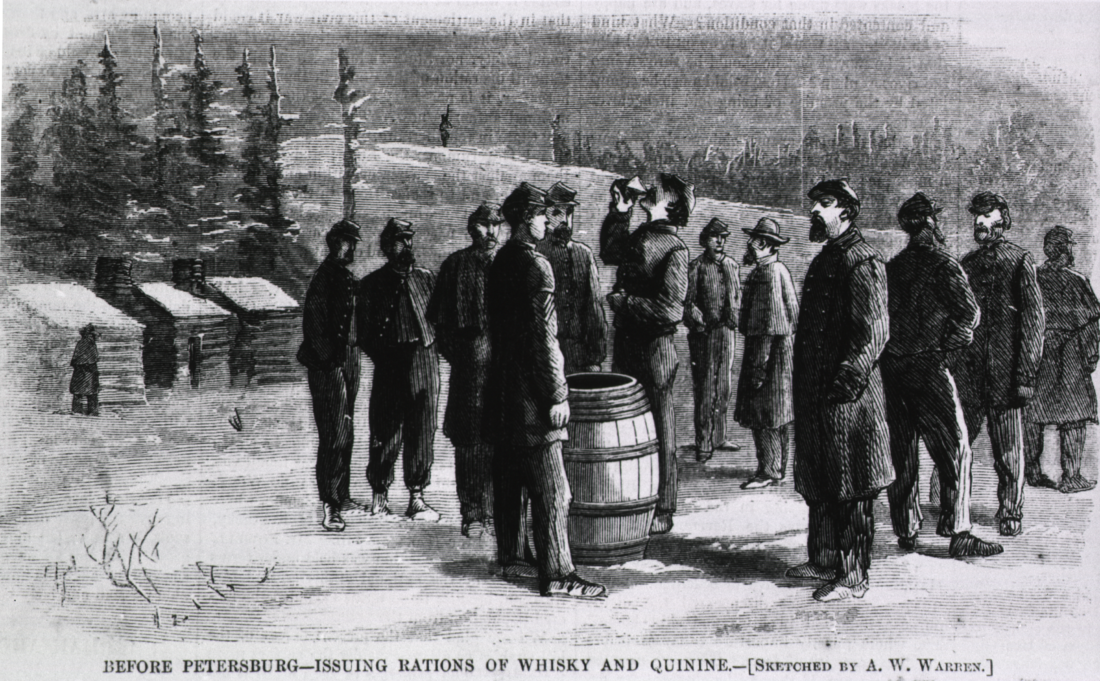

2. Mosquitoes helped win the Civil War

Not only did the Union have the upper hand when it came to weapons, manpower, and food, it was also rich in another valuable resource: quinine. A strategic naval blockade by the North choked the supply of the malaria medication to the Confederacy. While Union soldiers took daily preventative doses, malaria festered within the Confederate army, leaving sunken eyes and hollow cheeks. Smugglers attempted to sneak quinine past the blockade, stuffed in children’s dolls or the skirts of women disguised as nuns, but it barely made a dent in the number of soldiers falling to the disease. “Abundantly supplied Union troops and allied malarious mosquitoes had tapped and bled dry the fighting strength and spirit of the Confederacy,” Winegard writes.

Photo: U.S. National Library of Medicine

A drawing for Harper’s Weekly shows a Union “Quinine Parade,” as soldiers receive rations of the anti-malaria medication.

3. A Kentucky physician tried to kill Lincoln with yellow fever… and then became the governor

Before Dr. Luke Blackburn was elected governor of Kentucky in 1879, he was dabbling in biological warfare. An ardent Confederate supporter and supposed yellow fever expert, Blackburn secretly devised a plan to assassinate Lincoln by collecting bedsheets from yellow fever victims and selling them to a trade store near the White House. Convinced that the infected linens could kill a man from sixty yards, Blackburn expected the disease to sink its teeth into all of Washington, D.C., and Lincoln in the process. (It wasn’t until the 1890s that scientists firmly established mosquito bites as the culprit.) Yellow fever consumed the already war-torn South, and Blackburn himself traveled around the region to tend to victims. His devotion to the sick made him a likeable candidate for Kentucky governor, and he won in a landslide.

4. Mosquitoes almost wiped out Memphis

In the aftermath of the Civil War, “The mosquito…literally sucked the life out of Memphis and turned it into a city of crypts and corpses,” Winegard writes. The sudden growth in trade made the port city a hotbed for yellow fever, which decimated the population. By the summer of 1878, Memphis became a ghost town. More than half of its residents fled, and of the 20,000 people that stayed, 17,000 contracted yellow fever. That September saw an average of 200 people die each day before the chill of October curbed the disease’s winged perpetrators.

5. We can thank mosquitoes for our coffee habit

As you might recall from that Boston Tea Party in 1773, we were initially a colony of tea drinkers. But by the late 1700s, shunning tea in favor of coffee became as much a medical practice as an act of patriotism. As malaria festered in the South, doctors peddled coffee as an anti-malarial wonder drug. (It didn’t hurt that many Southern plantations were growing the beans at the time.) Coffee consumption increased dramatically as people hoped their morning cup of Joe would cure them of “agues and fevers.” Today, Americans drink 25 percent of the world’s coffee. As Winegard writes, “Starbucks ought to raise a toasting glass to the tiny mosquito.”

Garden & Gun has affiliate partnerships and may receive a portion of sales when a reader clicks to buy a product. All products are independently selected by the G&G editorial team.