I have been trying really hard to think of something new to say about Southern food, a subject that I (along with a host of other people) have written a whole lot about. I have written about funeral food and pimento cheese factions and George Jones versus Jimmy Dean sausage. I have attempted to prove the superiority of Southern cuisine with the all too easy comparison of our Junior League cookbooks with those from the North (Talk about Good! versus Posh Pantry; Aunt Margie’s Better than Sex Layered Cookies versus Grape Nuts Pudding). And I am still trying to prove the existence of the lone Mexican who introduced the hot tamale to the Mississippi Delta, where I grew up.

Whether or not this mythic figure ever actually roamed these parts is immaterial. The existence of the Delta tamale itself proves what I have long known, that Southern food is the Great Leveler. Hot tamales are beloved by rich and poor, black and white, and they are easily accessible at roadside stands, cafés, and restaurants. A dozen hots wrapped in shucks at either Scott’s in Greenville or the White Front Café in Rosedale sell for $8. The ones wrapped in paper at Greenville’s Doe’s Eat Place (the first solid food I ever ate) sell for a little more than $10. But then, pretty much all great Southern food is cheap. Wyatt Cooper, the late Mississippi-born husband of Gloria Vanderbilt and father of Anderson Cooper, once wrote, “The best French restaurants in the world are wasted on me. All I want is a few ham hocks fried in bacon grease, a little mess of turnips with sowbelly, and a hunk of cornbread and I’m happy.”

If this was Cooper’s menu of choice, then he was not only happy, but also rich—even without Gloria. I myself just returned from France, where I dined at two of “the best French restaurants,” L’Oustau de Baumanière in Les Baux and the Grand Vefour in Paris, and the bill for four people at each place put me in mind of what my father once said about a particularly pricey family ski trip to Aspen: “Next year, we don’t have to go—I can get the same effect standing in a cold shower burning up thousand dollar bills.” France in July might not have been as chilly, but each l’addition was considerably more than the entire tab for a brunch I gave for a New Orleans debutante the weekend I returned home. The deb in question is the daughter of one of my closest friends, and her special menu request was for an hors d’oeuvre I make consisting of a piece of bacon wrapped around a piece of watermelon pickle and broiled. I was delighted to comply—these little bundles are not only inexpensive, they are also salty and sweet and pair extremely well with the ham biscuits and pimento cheese sandwiches I alspassed around. The main course, 250 pieces of fried chicken from McHardy’s on Broad Street, cost me exactly $240.90. The debs had just been introduced to what passes for high society in my adopted city, and they seemed not just content but really happy to munch on some crispy chicken that cost less than a dollar per piece.

If Southern cuisine acts as a leveler by reducing the differences between race and class, the culture itself reduces the differences between—or the distinctness of—other cuisines introduced in our midst. Those Delta hot tamales bear little resemblance to Mexican hots, which I’m pretty sure are not bound together by lard and beef suet. Nor does deep-fried, bacon-wrapped, butterflied shrimp drenched in hot pink sauce on top of a ton of sautéed onions bear any resemblance to authentic Chinese cuisine. That particular item was my favorite thing on the menu at Henry Wong’s How Joy, another Greenville mecca, and it was what I thought Chinese food tasted like until I left home for school at sixteen. Morris Lewis, a prominent wholesale grocer from Indianola, not only left home, he was invited to China on a trade visit just after Nixon opened up the place, but he was still convinced that How Joy was the real—or at least the better—deal. Upon his return, Lewis said, “I’ve been all the way to China and I’ve still never tasted Chinese food as good as Henry Wong’s.”

Sadly, neither Henry Wong nor his restaurant is still with us, but almost all of my other favorites are very much around. And a lifetime of eating and cooking them has enabled me to come up with a few new things to say. For example, Southerners who put sugar in cornbread are impostors or criminals or both. Which does not mean I am a purist. I love “Mexican cornbread,” which, much like our tamales, does not come from anywhere near Mexico, but from a cookbook called Bayou Cuisine put together by Indianola’s Episcopal churchwomen. Among its ingredients are canned cream corn, marinated cherry peppers, Wesson oil, and shredded Kraft sharp cheddar.

Its utter deliciousness brings me to another important point: There is no shame in the occasional canned or packaged ingredient. Nora Ephron puts packaged onion soup mix in her justifiably famous meat loaf, and at least half of my mother’s repertoire would be decimated if there were no such thing as a Ritz cracker. She fries eggplant and green tomatoes in crushed Ritz crackers, uses them in place of bread crumbs or the lowly saltine in a squash gratin, and puts them on top of every other casserole she makes, including her V.D. Spinach, so named because she served it to every “visiting dignitary” who passed through our house, from Bill Buckley to Ronald Reagan. V.D. Spinach was recently chosen by Amanda Hesser for inclusion in The Essential New York Times Cookbook, despite—or maybe because of—the fact that it also includes frozen chopped spinach, Philadelphia cream cheese, and canned artichoke hearts.

Arkansas Travelers are the best tomatoes in the world, and all tomatoes are improved by peeling them. This latter point has been driven home to me all my life by my mother, who once peeled several hundred for the Katrina refugees who had evacuated to Greenville’s convention center as accompaniments to—what else?—fried chicken. More recently, my friends Ben and Libby Page hosted a brunch in Nashville at which they peeled and served huge platters of various heirloom varieties alongside their collection of Irish crystal saltcellars containing salts from around the world. This added a decidedly chic element to every Southerner’s favorite summer pleasure. When I visited Ben and Libby at their Tennessee farm last week, we had tomatoes from their garden, as well as skillet corn and squash casserole, a revered warm-weather trinity that leads me to my last point: Southerners have been doing “farm to table”—mostly by necessity—since long before the phrase was taken up by every foodie in the land.

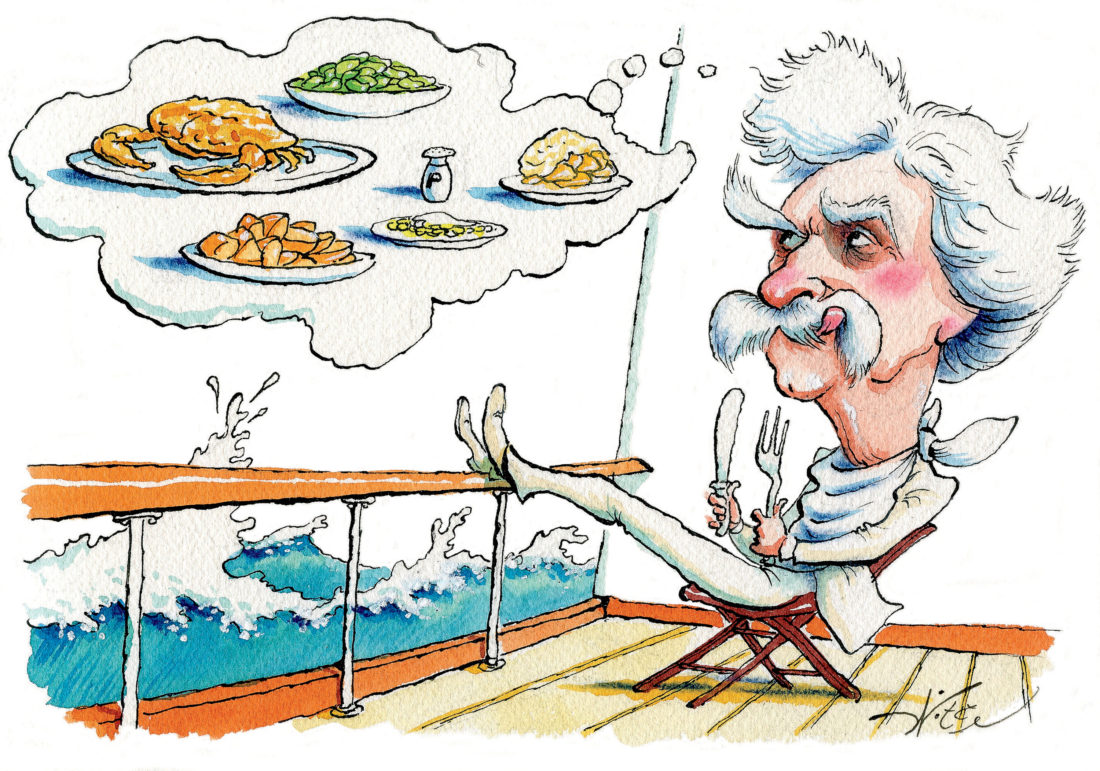

There is a reason, after all, that Mark Twain sent a lengthy bill of fare home ahead of him after he’d spent so much time in Europe. Among the things he’d missed the most were: “Virginia bacon, broiled…; peach cobbler, Southern style; butter beans; sweet potatoes; green corn, cut from the ear and served with butter and pepper; succotash; soft-shell crabs.” I am reminded again of Wyatt Cooper, as well as of the fact that pretty much the only thing I remember from my aforementioned meals in France was a side of tiny haricots verts just picked from L’Oustau de Baumanière’s garden and drenched in fresh butter. And then there’s the exchange between Katherine Anne Porter and William Faulkner that occurred at a swanky French restaurant that was probably Maxim’s. They had dined well and enjoyed a fair amount of Burgundy and port, but at the end of the meal Faulkner’s eyes glazed over a bit and he said, “Back home the butter beans are in, the speckled ones,” to which a visibly moved Porter could only respond, “Blackberries.” Now, I’ve repeated this exchange in print at least once before, but I don’t care. No matter who we are or where we’ve been, we are all, apparently, “leveled” by the same thing: our love of our sometimes lowly, always luscious cuisine—our love, in short, of Home.