Our first wedding anniversary was June 7, 2004, and I had orders to deploy to war. That day I kissed my wife, Katy, hard, wiped away what threatened to become more tears than I considered acceptable, and departed for three months of training followed by seven grindingly violent months in Iraq. Upon my return to Katy and Tallahassee, Florida, after western Iraq’s sun-blasted brown monochrome, the azaleas seemed to burst forth with an unusual glory of pink and white and fuchsia. I took a simple but exquisite joy in watching dogwood blossoms bob in the same breeze that carried the sweet smell of wisteria through our windows. Even the humidity that pressed close like a drunk friend felt welcome when contrasted against desert air so hot and dry it hurt to move.

I was ecstatic to be back and alive and reunited with my wife, but it took me longer than I expected to truly get home from Iraq. I found myself glued to twenty-four-hour news, seeking updates on the war. Solitude frequently turned my thoughts to the places where I had experienced life at the far ends of the human condition. I felt as if I had come in from a long day on rough seas. I was home, feet on flat ground, but my body was still rolling with the waves, waiting for potential catastrophic upset.

After about a month, my friend and fellow marine Jack called me and said, “Come get this dog.” “This dog” was a two-year-old yellow Labrador who had taken up residence in Jack’s home while we were deployed. I really wanted a yellow Lab, but Katy and her geriatric cat had been a package deal. She had never had a dog, and I wasn’t sure adding one to a young marriage so soon after return from combat was wise—especially as reports of violence in Iraq worsened, friends began to deploy for the second and third time, and I wondered when my time would come again.

Then the pictures arrived.

He looked like a cover dog for every hunting magazine I’d ever seen. He weighed about sixty-five pounds then. His dark brown eyes gazed out over a big pink nose that tipped an anvil-shaped head. In the photos, Jack’s three-year-old son sat astride the dog’s back, pulling his jowls up over his eyes, or the dog lolled on his back while cats climbed on his belly. I said I would stop and look at him at Jack’s house in Daphne, Alabama, on the way to my next marine reserve duty weekend in Mobile. I figured if I liked him as much in real life, I’d pick him up when I went home Sunday afternoon.

When we met, he was hooked to a cable around a tree. His ears drooped and he squinted at me, his tail lightly thumping the dirt. I checked him over, shook his paw, scratched his ears, and knew he was coming home with me. I told him I’d see him Sunday and drove away. I made it a hundred yards before I threw the truck in reverse, unhooked Earl (and he was Earl to me at this point), and opened the door so he could jump into the passenger seat. I didn’t have a bowl, a leash, or a plan, but I felt we were not meant to delay getting to know each other.

Those first few days were easy. Nowhere does a dog get more attention than in a pack of marines from Lower Alabama. Retrieving dummies emerged from pickups in the parking lot, and it soon became apparent that the “retriever” part of his heritage had skipped Earl. Nonetheless, he was happy to roll over for belly scratches. Three months earlier, these marines and I had followed the blast of plastic explosive into close-quarters firefights. Now we were all at the whim of a rambunctious young Lab. Earl and I slept next to each other on the floor of an office that weekend. When “our” duty was over, he jumped in my truck as if he’d been doing it his whole life and lay across the bench seat with his head on my leg as we drove home on I-10. In the years to come, he would prove to be more than a dog. For me, Katy, and eventually our daughter, Annabelle, he became whatever we needed him to be.

Of course no dog is perfect, so I should acknowledge Earl’s stubbornly disagreeable habits. Like most addictions, his affected all those who loved him. He could not restrain himself from sprinting as fast and far as possible through an open door, leading to lengthy chases at all hours. He lost his mind at the sight of water, the more fetid and foul the better, launching himself like a torpedo, ignoring demands to come out, and swimming to exhaustion. He was totally omnivorous, consuming coffee creamer cups, roadkill, and sand crabs alike. A wounded squirrel went down in one gulp like a shot of tequila. The following day saw a semidigested squirrel tail hanging from his backside until I put on garden gloves and helped him end his historic day as the dog with two tails.

But flaws aside, Earl was exactly what I needed to get me home. He lay on the couch with me as I studied during my last year of law school. He ran mile after mile with me through pine forests and live oaks draped in Spanish moss. We swam together, sometimes on purpose and sometimes with me cursing him as he pounded the water with his massive front paws until I could hook him with the leash and reel him in.

I graduated from law school in 2006, but with two wars moving in the wrong direction, I felt the nation needed me in the fight. I asked to return to the active ranks of the corps, and “Mother Green” welcomed us back with orders for Katy, Earl, Bernard the Cat, and me to move to North Carolina. Katy took a position practicing law in Raleigh, and I was assigned to Camp Lejeune, two and a half hours away. In a separation the Marine Corps calls “geographic bachelorhood,” Katy and I were physically apart for more than half of the next three years. Earl split his time between us, accompanying one of us to work almost every day and becoming an unofficial member of both Katy’s nonprofit and my battalion. One morning I discovered that a marine had photographed Earl in my camouflage uniform shirt, paws sticking out of the sleeves, and placed his picture in a line representing our chain of command, from the president down to Earl. During weeks that he was with Katy, I slept easier knowing he provided her an intimidating-looking escort in a sometimes-questionable part of town.

At Camp Lejeune, few days passed when marines did not visit my office to take Earl for a run or just to rub him behind his ears. When an altercation with another dog in North Topsail Beach left him minus part of an ear, the advantage of being a dog among marines and sailors became even more apparent. Marines showered him with concern while Earl-loving navy corpsmen applied antibiotics and changed his dressings twice a day. I believe he gave us all a respite from the omnipresence of Iraq and Afghanistan and the bad news about friends emanating from both.

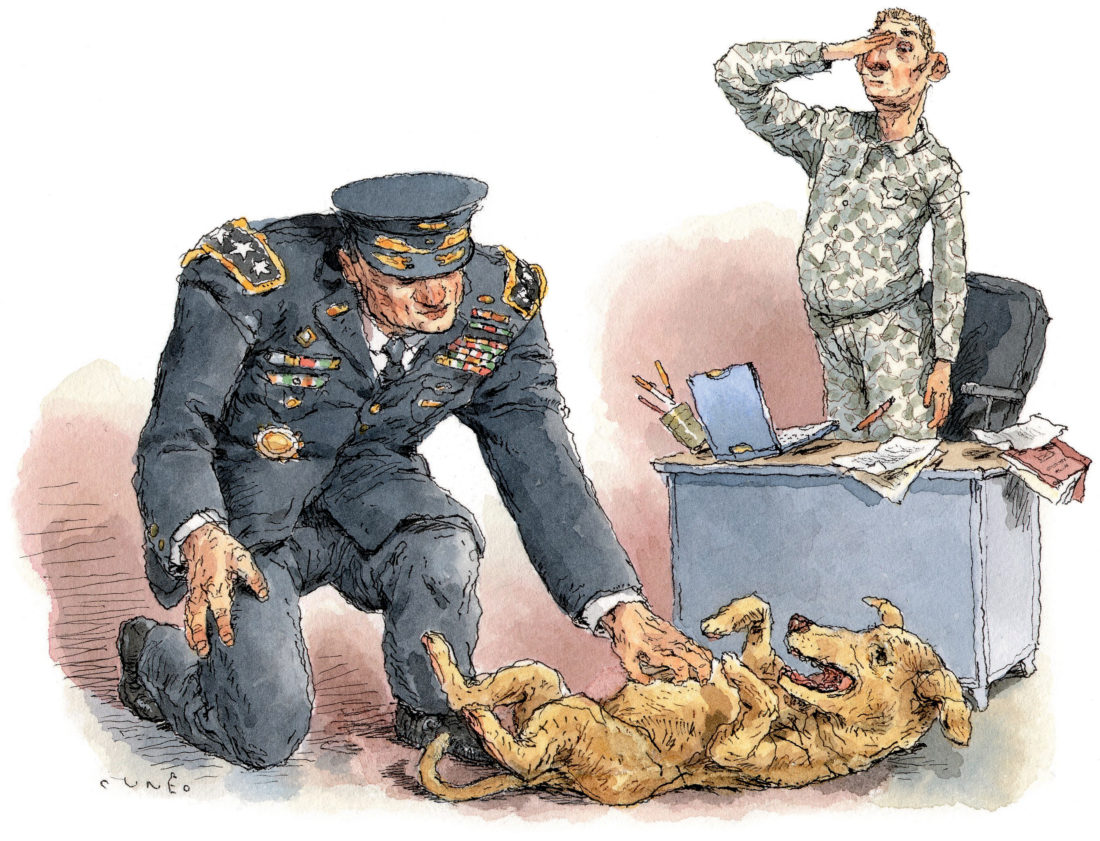

One afternoon, with Earl asleep in the middle of my office, on his back with his legs splayed in the air, I heard a very deliberate footfall rapidly approaching. I looked up to see our commanding general glance in as he passed by at a quick march. I heard his boots stop pounding the hallway. Suddenly, a Marine Corps major general was standing in my office demanding to know whose dog lay in the middle of the floor. Expecting an interrogation about my views on the propriety of a dog in a government work space, I came to my feet and acknowledged Earl as mine. The general broke into a grin and said, “He’s beautiful!” Then he collapsed to the floor to give the belly rubs an unconcerned Earl saw as his due.

In 2010, with Katy three months pregnant, I was deployed to Afghanistan. As always, Earl knew what was needed. Though I did not allow him into our bed when I was home, he happily snuggled up to Katy’s growing belly in my absence. I believe Annabelle’s increasing movement, pushing against his broad back, connected them. She was born six days before I returned from Afghanistan, and I was surprised to find that the ferocious bark Earl had previously reserved for drive-by barkings at herds of cows had become his standard reception for visitors at the door. Once the door opened, he still eagerly welcomed whoever was there, but that bark and his habit of stationing himself within paw’s distance of our new family member heralded a new Earl. The Great Protector. Or as Annabelle came to call him, Big Brother.

I left for Afghanistan again just before Christmas of 2013. By then Earl was showing his age. He was slower, with white dusting his face, but he was still strong. I received a steady stream of photos of Annabelle with Earl dressed up as a princess, a witch, a pirate. In almost all the photos from that time, Earl is either central or waiting patiently in the background. Where he had covered for me as a husband during Katy’s pregnancy, he now covered for me as a father. Loyal as a dog indeed.

When I got home the next summer, changes were apparent. Annabelle was blossoming from toddlerhood into childhood, and Earl was beginning the end of his life. He slept more, but that was fine. He still snuggled her during play and naps. He endured his role as her patient, dress-up model, or backrest while watching TV. But he began groaning when he lay down. Then he took longer to get down, lowering himself gingerly, as if into a hot bath. He stopped following us upstairs. I had to lift him into my truck, then even my wife’s much lower car. He developed a persistent cough. Then the vestibular syndrome set in, causing him to stagger as if he were drunk for days at a time, abating but leaving us all diminished after each episode.

By the spring of 2017, he would only totter a few feet from the door to attend to business, and I knew we had come to a new place. The sad-eyed veterinarian confirmed it. The chronic sneezing, hacking, and coughing we’d been trying to diagnose for the last two years was cancer. He’d survived life as a stray, lesions on his pancreas, a tumor on his muzzle, and a copperhead strike right between the eyes that left his snout swollen like a sausage and a three-day Quasimodo lump on his back from the IVs pumped into him to counter the venom. But this was the end, and I owed it to him to accept that.

The last two decades of my life have seen no shortage of sadness, violence, and loss, but when Earl’s final breath came, I still cried hard and ugly. I cried like a child cries, with the entirety of my body. I cried till I got a headache, my face a mess, my eyes run dry, just gasping and shaking. And in that, Earl gave me his final gift. He let me shed two decades’ worth of tears unspent for men and women gone too young, for time and family milestones missed, for things I can’t undo or unsee. I loved that dog the same way I cried for him, with everything I had to give. And he still outloved me.