In March, for the first time in history, the state of Alabama released an estimated 12,236 young Southern flounder into Perdido Bay. The fish were spawned and reared in the Claude Peteet Mariculture Center in Gulf Shores, of 100-percent wild fish genetics.

“This has been a long time coming,” says Max Westendorf, a biologist with the Alabama Division of Marine Resources and the shepherd to the state’s first flock of hand-reared wild flounder. “We’ve taken our lumps learning how to culture these fish, but we have high hopes for this program.”

High hopes are sorely needed. Across the South, efforts are underway to stymie a freefall in Southern flounder populations. Just this year, North Carolina shut down both the recreational and commercial seasons for flounder until late in the summer. Last year, Alabama cut its recreational flounder limit in half, from ten to five fish per day. In Texas, officials will meet in May to consider a seasonal closure this fall and an increase of the minimum size limits on flounder.

Culprits for the declines include overharvest, water pollution, and habitat destruction in estuaries, and Alabama’s move toward raising flounder with purely wild Alabama flounder genetics is one effort to bolster local populations while other conservation measures are in place.

“Stock enhancement is one piece of the puzzle,” Westendorf says. “It’s not a fix-all, but we’re learning that it can be a tool to help us get our numbers back up to their historic levels.”

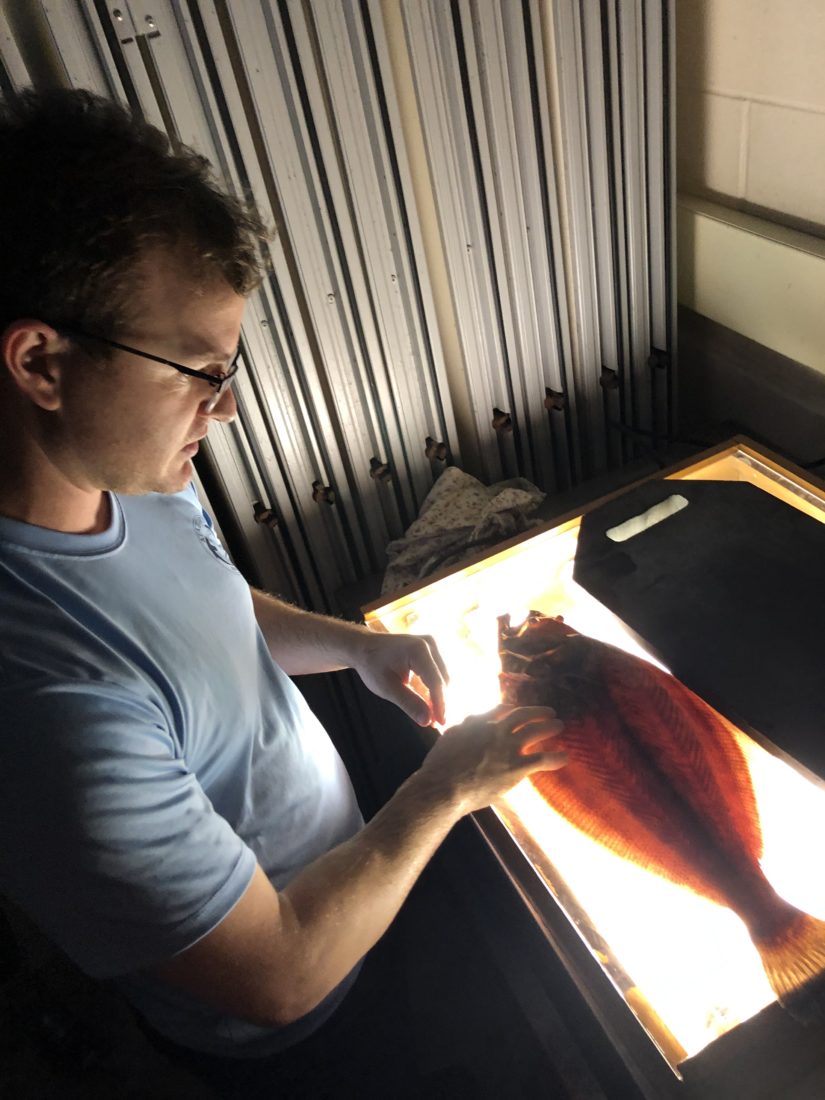

When Westendorf arrived at the mariculture center in 2017, he recalls, “there were maybe five or ten flounder in a tank, and they were not happy.” One of the biggest early challenges to the program was simply getting hands on wild female flounder with eggs. Researchers worked with anglers in Alabama Coastal Fishing Association tournaments and the Saltwater Finaddicts Fishing Tournament, literally parking a trailer at the weigh-in sites to hand-pick healthy females. Once word spread, a few anglers even dropped by the mariculture center with fish. Thanks to more than $165,000 in investments from the Coastal Conservation Association of Alabama, those fish were housed in refurbished holding tanks and specialized chilling tanks designed specifically for flounder.

And getting flounder to spawn is no small trick. “These fish have to be incredibly happy before they will put their resources into reproduction,” Westendorf says. Unlike pompano, redfish, and spotted seatrout—species that have long been bred in hatcheries—flounder are cold water breeders. Entirely new systems had to be designed and built. And the process is tailored to keep from swamping the wild population with related fish. “We’re not retaining offspring and then spawning them,” Westendorf says. “We use all wild fish, and we’re conscious of not using the same genetics year after year.”

Having passed their parasitology and bacteriology screenings at Auburn University, the freshman flounder class from Claude Peteet Mariculture Center—each one about 1.5-inches long—have now walked the stage. The state’s ultimate goal is upward of 70,000 wild-bred flounder a year.

“I was going to be happy with just one fish, just to show that we had cracked the code,” Westendorf says. “We don’t want to overwhelm the natural stock with too many hatchery-bred fish, even with their all-wild genetics. But hopefully this will give flounder a boost.”

And across the South, these flatties need it.

Follow T. Edward Nickens on Instagram @enickens