I read obituaries of mutts and curs every day in the newspapers. I don’t see why one of the finest purebred Brittanys shouldn’t have a eulogy.

Millie was the most extraordinary dog I’ve shot over in forty years of bird hunting. (Notice I didn’t say best.) And she was famous. At least at our house. Or infamous. My son Cliff was born when Millie was two. Cliff’s first words were “bad dog.”

Not that Millie was a bad dog. It’s just that she was… Well, “bad dog” does sum it up. But she never nipped or bit. In fact, she was selected for not doing so.

My friend Alex Bass had flown me from where we live in southern New Hampshire to John Hayes’s Kirby Mountain Kennels in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom. Alex owned a wonderful Brittany, Hannah, from a previous litter by the same dam. Hannah and Millie would hunt together most of their lives.

We’d narrowed the selection to two pups. While Alex was holding one, it bit him on the nose. I picked the other.

Millie didn’t bite. But she did everything else, almost immediately, from every orifice. We put her in a crate in the back of Alex’s Maule M-5. She whined piteously. I took her out and held her on my lap. We hadn’t been airborne for more than two minutes before all my clothing—shoes and socks included—was headed for a Hefty bag and into a garbage can with the lid on tight. “I contain multitudes,” Walt Whitman wrote. Millie, a much smaller animal than Walt, contained all that and more. Alex had to power wash the inside of his plane.

And Millie growled only once. When Cliff was four and Millie was lounging on the sofa, Cliff climbed the sofa back and launched himself butt first onto her midsection. It’s a wonder he didn’t kill her and a greater wonder that she left his behind intact. Instead she produced a baritone, fang-bared, Jack London–novel snarl, which was never heard before or after but was so ferocious that it forever gave me second thoughts about applying physical discipline.

Of which she needed plenty. The sofa where the snarl happened had replaced the sofa Millie ate. As a puppy Millie was confined to the TV room with a toddler gate. She gnawed on the sofa, but it was an old sofa, due for a new slipcover. Then one night she ate it. She ate almost all of it. So little of the sofa remained that I was able to carry it out to the trash in one armload.

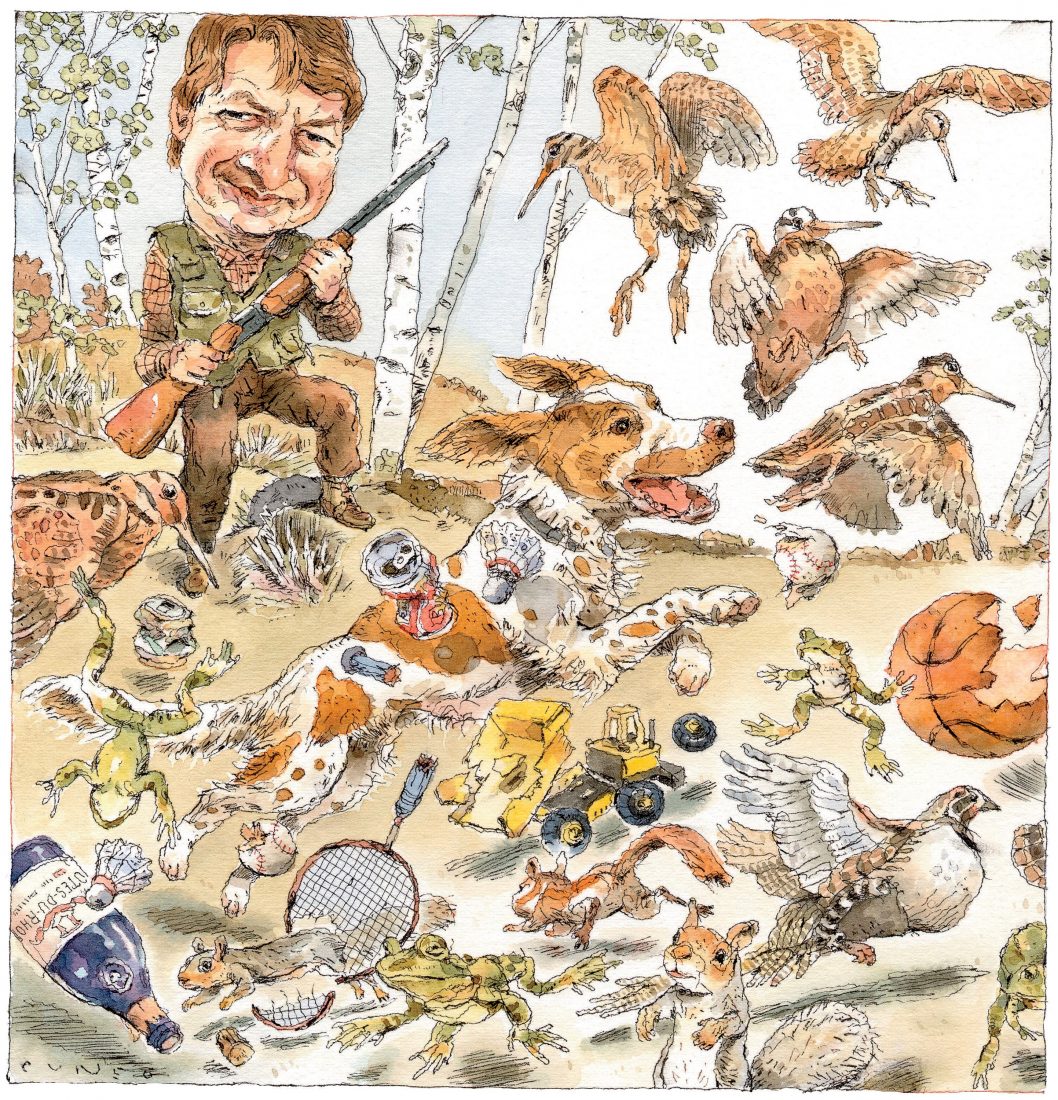

There wasn’t much that Millie wouldn’t chew, not just when she was a puppy but for the next thirteen years. She chewed baseballs, croquet balls, basketballs, the floor mats in my car, rake handles, empty beer cans, the Tonka trucks in the sandbox, the sandbox, and the sand in the sandbox. She chewed the badminton net, which required a leap of four feet.

Millie would chew anything except dog food. She wasn’t interested in dog food. When she first came home, I had to entice her to eat with handfuls of wet kibble. (Which, my wife points out, is more than I ever did by way of feeding our children.) We have three other dogs. Millie never objected to their muzzles in her dish.

But Millie could pry into and empty all the kitchen cabinets, nose open the refrigerator door, and paw the pedal of the garbage bin to make its top flip up.

As a food thief she had stealth, swiftness, and timing. At a game dinner we had just poured a treasured bottle of 1990 Côtes du Rhône when Millie snatched a whole roast mallard from the table. And spilled the wine. And ran into the woods. There she stayed with her fine dining until 1:00 a.m., by which time an equally treasured bottle of single malt had rendered me unfit to give her hell.

Luckily for Millie’s future anywhere outside an ASPCA pen, she brought even more grief to living woodcocks and ruffed grouse than she brought to dead ducks. She was a natural hunter. Which is to say I couldn’t train her.

I had my copy of Gun Dog by Richard Wolters. I did everything the revered Wolters said. This meant (to my wife’s horror) I had a ziplock bag of frozen grouse wings in the freezer. I attached one to a fishing pole line and stood in the yard swinging it in circles—the way Wolters claims gives a puppy its first chance to point. Millie pointed. But in the opposite direction of the spinning wing. And on the next rotation she ate it.

Millie would “sit” when she felt like it, “stay” if she was in the mood, and “come” according to whether the spirit moved her. Given the command “Whoa,” she would look around to see whether there was anything worth whoaing for, then sit, stay, or come.

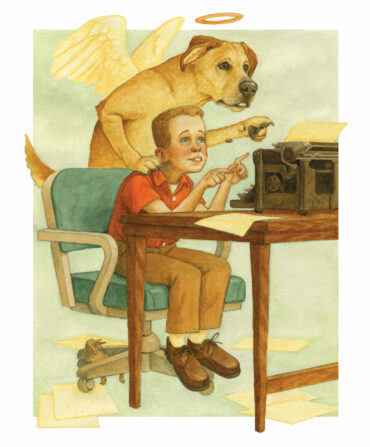

But Millie was brilliant in the field. All that I can figure is she trained herself. She carefully watched Alex’s dog Hannah, two years her senior. She’d trail Hannah and honor every point.

Then I took her out on her own. We went into a tangled old alder cover with—to my knowledge—only a few native woodcocks. But a migrating flight had landed, thirty or forty birds. The result was the 1963 thriller by Alfred Hitchcock with me as Tippi Hedren.

Woodcocks were flying straight at my face. None having been pointed. Millie was a fast dog, a very fast dog, the Usain Bolt of Brittanys. Despite weighing only about twenty pounds at the time and dragging five pounds of soaking wet check cord behind her, Millie took the Olympic gold, silver, and bronze in running around like a maniac.

When all the birds were gone, Millie stopped. She seemed satisfied, as if she’d gotten rid of something that annoyed her. The cover had had too much scent, like Chanel No. 5 on Coco.

Millie trotted to a seam between the alders and a hardwood forest. I trotted after her. She pointed. I put a woodcock up and shot it. Millie found it and retrieved. She trotted another twenty-five feet and pointed again. Same thing. And the same again a third time.

Thereafter Millie almost never bumped a bird. I say almost. If the bird had the sense to freeze, it was in danger from nothing but my shooting. (I have wisdom to impart about shooting—not for the readers but for the birds. They learn a lot from me about how to avoid shotgun pellets.) However, if the bird didn’t have the sense to freeze, if it made any movement that Millie saw—and Millie was a gazehound as well as a pointer—then…Millie often emerged from the bushes with a bird no one had shot.

Millie had cover sense. If I sent her into a cover where there were no birds, she wouldn’t go. If I sent her into a cover where there were birds, she wouldn’t leave—no matter how bad the weather or how dense and impossible the cover or how long ago I’d gone back to the car to have a nip from a flask because the sun had set.

Millie had bird sense. She wasn’t fooled by ground scent. She didn’t care where birds had been. She only cared where birds were now. And she usually knew where birds would be next.

Once I put up a woodcock she’d pointed and the bird “towered” the way woodcocks are supposed to instead of jinking like the dickens. I shot it straight up in the air. Millie caught it in her mouth.

She was infallible when “hunting dead.” This is important with woodcocks, which—for unknown Darwinian purposes—are reasonably easy to see on the ground when alive but perfectly camouflaged when dead. If Millie didn’t find the bird, you were lying about having shot it. On the other hand, she could tell when you had.

In her first, still-a-puppy season, I was behind with both barrels in my lead on a pass shot. But Millie wouldn’t stop running around the trunk of a beech. Millie did like to run around. It was ten minutes before it occurred to me to look up. The carcass of the unlucky woodcock was wedged in a branch.

Millie was oblivious to weather and impervious to fatigue. The only times I saw her tired were on hot fall days, and I could tell she was tired only because she’d run around as fast as ever but not find birds. Dogs perspire with their breath, so it makes sense that panting spoils their sense of smell—as though we had to pick up small objects on a warm day with our slippery armpits.

Splendid as Millie was in the field, getting her there was misery. She had a special high-pitched bark reserved for being closed in her crate in the back of my Suburban. When let out, she ravaged the cooler, masticated the thermos, and insisted on riding with her hind paws in the center console cup holders and her forepaws on the dashboard so she could spread nose prints all over the windshield. She was a nervous passenger ever since that first plane ride. And she had reason to be nervous. She made it hard to see the road ahead and impossible to look both ways at intersections.

Millie liked to run around. She also liked to run away. But “run away” makes her sound furtive. She was too proud for that. She simply went where she wanted to go. The first time she got to a hunting field, before her bell or electronic collar had been attached, she wanted to go a mile into the woods. It was an hour before she began barking and we could locate her. She wasn’t lost, her attitude indicated, but she was very irritated that she hadn’t been found.

We put our phone number on Millie’s collar. During her first eighteen months, she turned up miles away on a mountain trail eating a hiker’s energy bars, going from shop to shop soliciting treats along Main Street in the nearby town, and making courtesy calls on every dog-owning family in the county.

I bought an invisible fence, but it came with a paltry hundred yards of wire. I couldn’t deprive Millie of the hay field below our house where she caromed like a furry billiard ball shot from a pirate ship cannon. I had to buy fifty-pound reels of braided, insulated industrial wire and hire a boy to help me run a mile-long fence loop through the surrounding woods. It cost nearly as much as keeping a SEAL Team 6 helicopter on call to perform Millie renditions.

The invisible fence was one thing Millie respected. I think she was embarrassed to be zapped like a Looney Tunes character with her skeleton visible and her hair all mussed up standing on end.

And the fence allowed Millie to become “frenemies” with a fox. Millie knew where the invisible fence was buried under our lawn. And so, it seemed, did the fox. In the morning the two of them would stand twenty feet apart and bark happily at each other without danger of this turning into an unseemly brawl.

I mentioned that Millie retrieved. Literally that was a half-truth. Millie would pick up a bird and bring it exactly 50 percent of the way to me. To come farther was beneath her dignity. She wasn’t a retriever. That was our dim-bulb black Lab eating Millie’s dog food every night.

My kids would throw a tennis ball for the two dogs. The Lab, if she could somehow get to it first, would fetch the ball. Millie would snatch it and prance around with the ball in her mouth until someone chased her. Millie wanted to fetch you.

She was a beautiful dog. And she knew it. There’s a large rock in our yard that she’d sit on. I’d peek out the window and catch her preening when she thought no one was looking.

And she was fastidious. She never relieved herself on the lawn but modestly concealed herself in the shrubbery and always went to the farthest corner of the “pet area” at a highway rest stop.

She was paper trained as soon as paper was put on the floor and house trained in a couple of weeks. But she was sneaky about it. A three-car barn was attached to our house. We were house training her in the winter. I’d let her out the house door, then out the barn door. She’d come back in the barn and bark to be let into the house. Not until spring did we realize that she slipped behind the tarp-covered summer car and went to the bathroom inside all winter.

When Millie wasn’t hunting, she hunted. At ten weeks she dove into the snow and emerged with a crunched vole. She hunted chipmunks in our stone walls, squirrels in our trees, mice in our basement, june bugs on our porch, and—her favorite—frogs in our pond. I have a seventeen-year-old vegetarian daughter who claims to have been permanently traumatized at age eight when Millie emerged from the pond with a frog in her mouth, frog legs sticking out and frantically wiggling. My daughter protested, “Millie!” Millie responded, “Gulp.”

Millie was fond of the children, especially the eldest, the vegetarian. She’s as hard-headed a girl as Millie was a dog. The other two kids and three dogs were treated with courteous condescension as one would treat paid entertainers—the band at your wedding reception.

Millie tolerated my spouse, Tina. The dog regarded my marriage as polygamous. She considered herself the senior wife. Tina and I had been together for a decade before Millie arrived. But, to Millie, Tina was always the cute young girl who had caught the old goat’s eye. Nonetheless, Tina was a young girl with a pleasant personality who was useful for chores around the house.

Millie sometimes did what Tina asked, when I was there. When I wasn’t, Millie didn’t. I was on a business trip and Tina was trying to get the dogs in. Millie came as far as the mudroom steps and no farther. Tina stood on the mudroom steps waving a slice of bologna in Millie’s face. Millie stared at her.

But when I was gone, Millie would also talk to Tina. Millie was a talking dog. But not in a carnival sideshow way. She’d stand in front of you and make the full range of sounds that dogs can make. She didn’t want out. She didn’t want a table scrap. She wanted to get something across.

And when I was gone, she’d pull my hunting clothes off the hangers in the mudroom closet and make a nest. She never chewed hunting clothes. Or only once. I went on a quail-shooting trip and didn’t take her. When I got back, she chewed the tongues out of my best hunting boots.

Last season Millie was suffering from the asthma that would kill her. She made a show of hunting but could only last ten or fifteen minutes. By then I had a new young Brittany, Clio. Millie was friendly to Clio but didn’t pay her much attention. By then Millie was spending all day every day in my office, in a club chair that she had, with strategic chewing and years of shedding, made all her own.

On Millie’s last hunt, I put Millie and Clio on the ground together. Millie was still fast, in short bursts. She ran to an old apple tree and went on point. Clio, less certain, sniffed the air and meandered until she was opposite Millie. Then Clio went on point too. I could see the ruffed grouse on the ground. It was holding. Millie could see it too. Millie looked at the grouse. Millie looked at Clio. Then Millie walked back to the car and lay down. She’d turned the family business over to Clio. I shot the grouse.

Five months later Millie had a severe asthma attack. We tried to get her to the twenty-four-hour emergency veterinary hospital in the nearest city. For once she didn’t perch on the dashboard. She nuzzled my hardheaded daughter in the backseat. Millie died halfway through the trip. I went out to the car in the morning to say goodbye. Millie’s last living act had been to chew the blanket we’d wrapped her in.