For many years, I thought that owners of small dogs harbored stunted souls. Parents of infant beauty queens. Weird bachelors with pet stairs by their beds. Adult hoarders of dolls and teddy bears. People deranged by an obsession with the adorable.

Then, in my late twenties, when I was living in New Orleans, a good friend of mine found a bedraggled Chihuahua in a ditch and brought her home. It was a comical, toothless animal with a bullfrog’s tongue that would slap her in the eye on the recoil. That dog had a lot of ditch trauma to work through. She needed to sit on somebody at all times or she got the shakes. I was home most days, so I let the dog make use of my lap during business hours. When I moved back to North Carolina, I was surprised to discover a Chihuahua-size hole in my life.

So I started looking for a dog. I knew I wanted a pound animal, though not for any lofty moral reasons. I wanted a desperate dog, one without high expectations of whoever took it in. My family had dogs when I was a kid. The bunch of us should be arrested for how we let those animals down. They were outdoor dogs too disgusting to pet. We let ticks get on them and grow as big as minié balls. When the family went out of town, we’d leave the dog on the porch with a bag of cheap food. Eventually, they’d get sick of us and wander off. So my track record with dogs wasn’t the greatest, but I figured one otherwise bound for the gas chamber couldn’t really gripe about winding up in my care.

I spent long hours at the keyboard, browsing head shots at an online clearinghouse for discarded dogs. A Chihuahua was what I was after, but I didn’t want it to be too grotesque: too bug-eyed or hog-snouted or bat-eared or obviously rodentlike. Looking for an ungrotesque Chihuahua is like trying to find a dignified clown. It took a good bit of time.

At last, I found a candidate. The head shot showed a creature with a long, aristocratic nose and smart, Dobermanly ears. Her eyes were large but not hyperthyroidal. They seemed to reflect intelligence but also the right measure of desperation. She was waiting on death row at the dog pound in Winston-Salem, ninety minutes from my home. I gave them a call to see if the dog had yet been gassed. “Nope, she’s still here!” an exhaustingly jolly Southern voice exclaimed.

“Oh, you will just love this crazy little creature. We call her Tinsy, but you could call her Teensy-Meensy-Weensy-Eensy! She is that small! She’s one of them little reindeer dogs, you know. She’s just always bouncing all around on them little teensy reindeer legs. She is kinda licky and kinda barky but she’s a funny little ball of fun.”

I was in the market for a lap sleeper, a hot-water bottle in canine form. From the sound of it, this reindeer dog embodied much that is dislikable in the miniature breeds. But I had committed to paying the dog a visit, and I make it a point never to betray a promise to the incarcerated. I went and had a look. The lady I talked to on the phone dragged Tinsy out from where she’d been hiding behind a file cabinet. Tinsy, who was maybe a year old, had been found walking the streets of Winston-Salem naked. Like most women found in this condition, she was not in the greatest shape. She resembled a dog the way those caiman-head back scratchers resemble an alligator. Her face was okay, but the rest of her body was a bony rod upholstered in bald gray skin. I had seen rats with prettier tails. Hers was without a whisker and looked as though it had been set afire and extinguished under the needle of a sewing machine.

“You wanna hold her?” the shelter lady asked me, wagging Tinsy at me like a dishrag. I did not want to hold Tinsy. I wanted to leave the room. But Tinsy was thrust into my arms. This dog had long, scraggly talons, and she clung to my sweater like a bat to a screen door. I grimaced. The dog grimaced. “That’s a wrap!” cried the shelter lady. “That is your dog. She is absolutely your dog.”

I wanted to tell this woman that I wanted Tinsy like I wanted a case of shingles, but courage failed me. I wrote a check for the adoption fee. Then I carried the dog to my car and began calling every softhearted person I knew to see if they would take this creature off my hands.

At home, I took to my couch and fretted. What business did I have with a dog? I traveled for work eight months out of the year. And this dog? I didn’t want to look at her much less look after her for the twenty years Chihuahuas can expect to live. Then the dog, who had been busy peeing on my bedroom floor, wandered over. She tilted her head at a sympathetic angle, then she jumped onto the sofa and clambered onto my shoulder, where she pulled herself into a sphere and went snortingly to sleep.

How easily we are gentled. The plan to ditch her got ditched. I started calling her Edie, whose vowel sounds she hearkened to as she had her prison name. I loaded her up on ludicrously expensive foods: Alaskan salmon, mutton jerky from New Zealand. She doubled her weight, from two pounds to four. I put her through expensive mange treatments, fed her fish oil, greased her in vitamin E to regrow her hair. After a couple of seasons, she fluffed out and the knobs of her spine receded. She began to look less like a back scratcher and more, as a friend described her, “like a cross between a wolf and a flea.”

“No man should have a dog like that,” my cousin once said to me. “We’re not careful enough. You could drop the Sunday paper on her and break her back. It’s like getting a crystal set. No guy should have a thing that fragile in the house.”

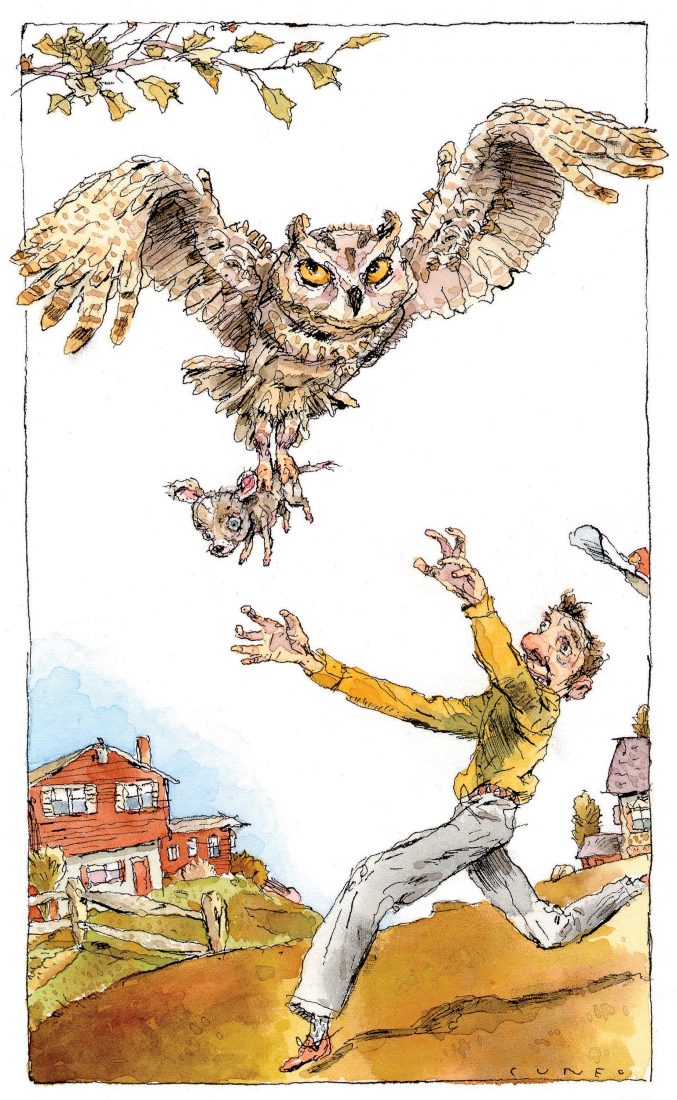

And it’s true. Owning Edie is nervous work. A few years back, I nearly lost her. Summoned from the house by the sound of raving crows, I went out to check on Edie in the yard. She was absent from her usual sunbathing spot. In the lower corner of the lawn, I saw a barred owl, spreading its wings over a small, still gray form. Edie was too heavy a piece of live cargo for the owl, so the bird was patiently trying to murder her. I nearly had to kick the bird off of her. A talon had made three bloody divots in Edie’s head, but no lasting damage was done.

At nearly twelve, Edie is deep in middle age and, repairwise, is not much less expensive than a ’55 Studebaker. I’ve put far more money into her mouth than I’ve put into my own. Before I got Edie, I’d have said that a fair definition of an insane person is somebody who takes out a thirty-three-hundred-dollar cash advance to pay for exploratory liver surgery for a dog. I did that three years ago. But when you get accustomed, every night, to a warm gentle presence stretching herself across your clavicle and easing you into sleep, it becomes as dire a habit as barbiturate abuse. Addicts do crazy things to keep withdrawal at bay.

It’s weird. One day, you’re a twenty-eight-year-old man of traditional tastes and accoutrements and the next, you’re a forty-year-old bachelor with a four-pound, big-eyed, molting pussy willow of a dog.

Still, I do what I can to keep the grotesquerie contained. When people ask what kind of dog I have, I tell them, “I don’t know, I got her from the pound.” I do not carry Edie around in a Snugli. I have never bought the dog shoes or a hat. I would like to tell you that my home contains no doggie sweaters, and that there are not dog stairs by my bed, but this would not be true.