The 1948 Green Book.

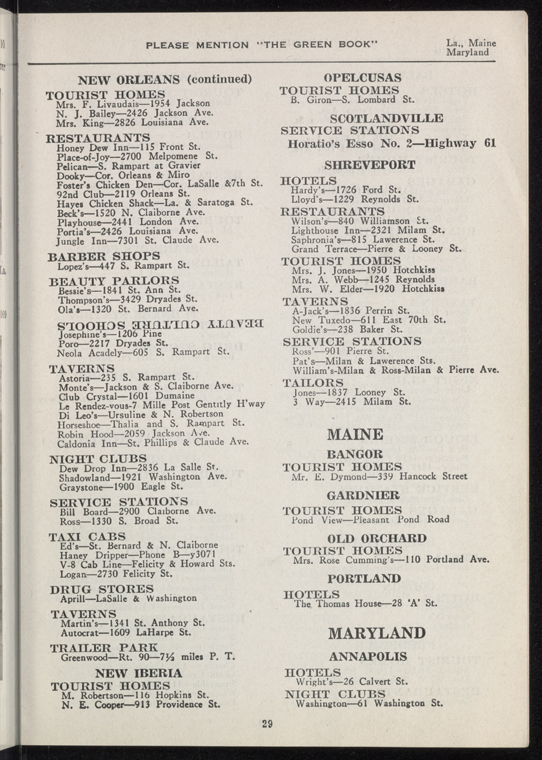

There is no stack of the Green Book guides—lately famous because of the Green Book film—lurking forgotten in the back of a closet at my house, even though I grew up in New York, where Victor H. Green & Company published the Negro Motorist Green Book from 1936 to 1966 to safely guide African-Americans on their travels during the Jim Crow era. However, when I first perused a copy for 1948, the year I was born, I was delighted to see the name of my favorite New Orleans restaurant, listed simply as “Dooky,” at the corner of Orleans and Miro, where it still stands today. Dooky Chase’s restaurant is a survivor! Opened in 1941, the venerable institution has, unlike so many of the restaurants and taverns, nightclubs and hotels listed in the guides, weathered the storms of history and gentrification and discriminatory urban planning to become a witness to an era. (One author has estimated from her research that only around 3 percent of Green Book sites remain in operation today.)

New Orleans listings in the 1948 Green Book.

I’d known Dooky Chase’s was important when I first visited New Orleans in the 1970s, on assignment for Essence magazine. By then, it had served as not only a welcoming restaurant for traveling African-Americans, but as a crucial eating-and-meeting spot for civil rights activists of all races, such as the Freedom Riders, at a time when such gatherings were illegal. “They met here, and they knew that nobody was gonna disturb them,” Leah Chase, the spot’s legendary matriarch, told me when I interviewed her last year. “Nobody would raid this place, ever.” It was sacrosanct, she said. My distant memory of that initial visit is of a small spot with a counter and stools and a few tables and chairs. Then, there were no photographs of presidents dining there or signed Disney posters from The Princess and the Frog (the cartoon is based on Leah’s life). But it was clearly a much-loved neighborhood spot where the food was very good and the welcome very warm.

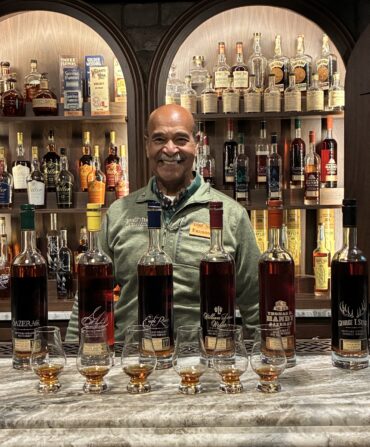

Photo: Chris Granger

The dining room at Dooky Chase’s.

When I visited New Orleans again almost two decades later, Dooky Chase’s had expanded to its present size and taken its place in the city’s dining firmament. In the subsequent years, the restaurant has become a must-do on every trip I make to the city I now consider my second home. I knew Dooky Chase, the son of the original owner, who died in 2016; his wife, Leah, whom I now call “Aunt” Leah, has become a friend and trusted advisor. For almost a decade, I hosted an annual Holy Thursday luncheon there, introducing friends from around the world to her once-a-year green gumbo, her must-taste fried chicken, and sublime shrimp Clemenceau.

Photo: Cedric Angeles

The author in the kitchen of Dooky Chase’s with Leah Chase.

With every visit, I’ve learned more from the Chases about the role that the restaurant has played in the social history of New Orleans and the South. “You did things back in those days and you didn’t consider yourself changing anything,” Leah told me. But I believe that the family’s continued uplifting of and involvement in their community not only allowed it to survive past the Green Book era, but to thrive. In addition to harboring civil rights activists such as Martin Luther King, Jr., the Chases nurtured and supported black artists, giving them gallery space on Dooky Chase’s walls; sustained musicians both local and visiting, from the Jackson Five to Mahalia Jackson, as Dooky himself had been a jazz trumpeter and band leader; and most importantly, served as a hub for African-Americans in bad times and good. “Dooky used to say to me all the time, ‘You’re never satisfied,’” Leah recalled. “I think as long as you’re living, you should try to grow, try to raise yourself up. Raise somebody else up with you.”

Photo: Chris Granger

Leah Chase photographed in 2011.