You know the old Christmas-morning story: A child finds that Santa has left him or her an enormous pile of manure. Under the tree somehow, I don’t know—but here’s the moral: The child, being an optimist, is delighted. Because “there must be a pony here somewhere.”

Me, I don’t need a pony. But if Santa brought me one, my eyes would light up. Because must be some manure around here somewhere.

It’s like manna from heaven for your compost. Wendell Berry, from his poem “The Man Born to Farming”:

He has seen the light lie down

in the dung heap, and rise again

in the corn.

“I saw some grand manure the other day,” wrote Eudora Welty in a letter to Diarmuid Russell, her agent, friend, and fellow gardener, “and thought of you.” She went on to say, “It was well rotted manure—practically antique. But I had no way to make off with it. I carry scissors, diggers, and hatchets, but no manure compartment in my car.”

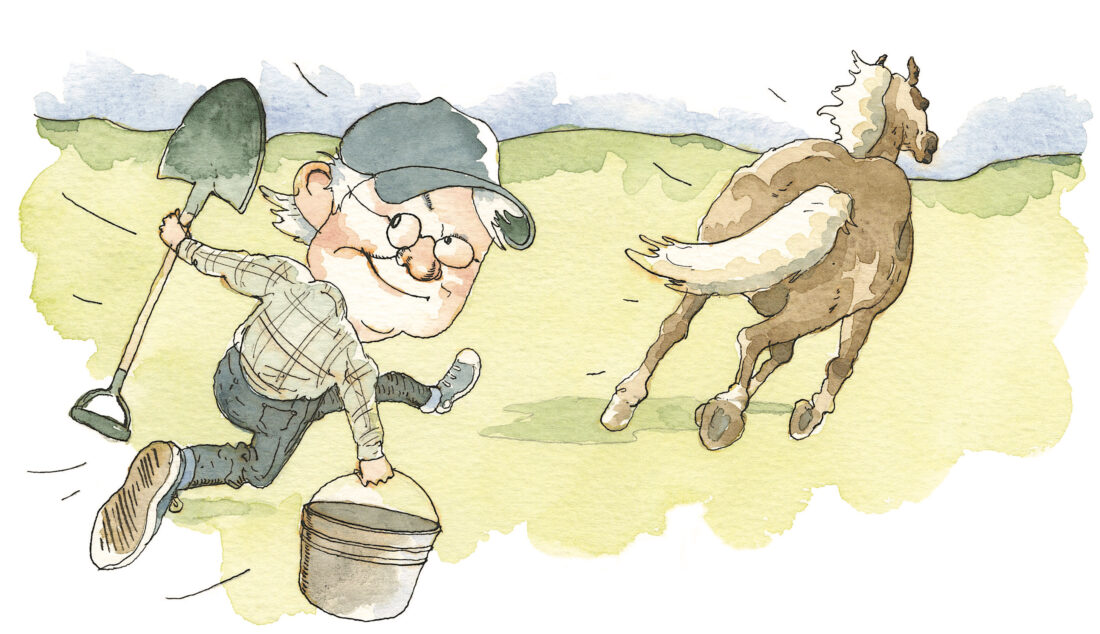

There is where I am one up on that great Southern writer. In my trunk I keep a shovel and a bucket. A neighbor up the road has posted online that she has a big pile of horse and cow manure available to all, and I have gone there multiple times.

Russell wrote back to Welty: “After fertilizing my garden, I had manure to spare, so I fertilized my grass as well. Next year I expect to have a lawn such as only gods can sit on and not feel embarrassed.”

You see there how manure may lure someone to ostentation. As Mark Twain traveled through Germany’s Black Forest, he was struck by the dung piles in front of the nicer homes: “We became very familiar with the fertilizer.…When we saw a stately accumulation, we said, ‘Here is a banker.’ When we encountered…an Alpine pomp of manure, we said, ‘Doubtless a duke lives here.’ Manure is evidently the Black-Forester’s main treasure—his coin, his jewel, his pride, his Old Master, his ceramics, his bric-a-brac.”

Twain’s note to himself: “Skeleton for a Black Forest Novel: Digging, three days agone, I struck a manure mine—a Golconda, a limitless Bonanza, of solid manure! I can buy you ALL, and have mountain ranges of manure left!”

Me, I don’t want to look manure rich, I just want my compost heap, which is, to be sure, visible from the road—I want my compost to be rich.

In Flannery O’Connor’s fiction, manure spreaders are a trope. As in the opening paragraph of her story “The Jesus Flag”:

“If God, in cursing Lot’s wife, had turned her into a pillar of sugar instead of salt, Mrs. Wilhellper would have fit the bill. With her tight bun hairdo and squat body resembling a bush, she was five feet three inches of sweetness as determined as a dump truck. She had two sayings—‘Too Sweet for Words’ and ‘Perfectly Marvelous’—which she uploaded on every aspect of the universe as relentless as a manure spreader covering a green field.”

If there is any such irony in my down-the-road neighbor’s bountiful offering of manure, it would be that the horse and the cow of that farm tend to hang out together under a tree just over the fence from the pile. As I’m shoveling up a good big bucketful, the two of them—actually, it’s mainly the horse—will give me a look as if to say, “Uhh, you know what that is, right?”

That horse is like so many of us. We don’t appreciate our own down-to-earth productions—although those productions’ values may be more resounding than the hoity-toity know. The Texas-born art critic Dave Hickey told me once that among New Yorkers, he preferred those who come from Texas, “because at least they’ve been in two places.” In an essay about the abidingly classic Italian villas designed by the Renaissance architect Palladio, Hickey wrote: “Some scholars…argue that the villas never were intended to be ‘real’ farmhouses with…usable stables, but rather were meant to be genteel ‘ceremonial’ farmhouses,” because “horses smell bad.” Hickey observed that “theorists like this kind of angle,” because they think it qualifies the five-century-old villas “as serious, canonical ‘critical architecture’ by contemporary standards.”

Hickey cites three mistakes these theorists are making. Two of the mistakes are aesthetico-historical. The third, which he calls most egregious: “for horse people, nothing about a horse smells bad.”