I was a little more jaded than most freshmen starting their first year at UNC. My family moved to Chapel Hill, North Carolina, when I was a kid. I’d gone to middle and high school there and missed out on the “freshness” of the freshman experience: I knew campus and its culture well and was already a regular at most of the hot spots up and down Franklin Street. My disappointment at not going off somewhere more exotic to pursue my college education was acute. But a campus as large as UNC’s still had some surprises in store for me. That first year, I fell in love with a graveyard.

The Old Chapel Hill Cemetery, formerly the College Graveyard, was established in 1797 as part of a land grant by the state. Originally intended for the interment of students and faculty who died during their time at the university, it nevertheless reflects the broader cultural history of the area. Because there were no Black church cemeteries in Chapel Hill until the nineteenth century, people of color were buried in the segregated section—often in unmarked graves or under uncarved field stones. They lie uncomfortably close to Confederate soldiers. Other notable residents provide a portrait of the town’s evolution over time. Here you will find Wilson Swain Caldwell, Dean Edwards Smith, the deans of many of the university’s professional schools, novelists and musicians, and the proprietors of many beloved shops and restaurants that have served the community for decades.

Expanded in 1928 and deeded to the Town of Chapel Hill fifty years later, the cemetery presently occupies about seven acres between the Center for Dramatic Art and South Road, the rough dividing line between the humanities and the sciences on campus. As a dramatic art and English double major, I spent plenty of time at both the CDC and Davis Library, busily pursuing angsty adolescent fixations on Shakespeare and the Victorians. But for some inscrutable administrative reason, the first class in my creative writing minor was held in a biology building, and the quickest way to get there was through the cemetery. Before long, its quiet, shaded walks became an oasis, a refuge from the hum and roar of the medical school and the stadiums, the hustle and bustle of the dining halls and the student union.

I preferred to eat my lunch alone in the cemetery’s gazebo with only a book and the dead for company. I had already discarded the dogma of my Roman Catholic upbringing but maintained a morbid fascination with all things gothic and whiled away the afternoons wandering among old headstones adorned with ivy, wondering why that person died so young, or why that one chose, of all things, a possum to mark their final resting place.

The cemetery was where I watched the seasons change, without thinking much about how the years were flying by. The magnolias kept their leaves while the dogwoods shed theirs; sunlight flashed off the marble obelisks in springtime; more modest plaques and fieldstones disappeared under our thin, fleecy dustings of snow. As the seasons changed, so did I. I left my teenage years behind, and the Victorians, too. I gave up my daydreams of being an actor and embraced my creative calling as a writer and scholar instead. But I kept coming back to the graveyard, until I graduated and left not just the town but the whole country behind.

My graduate study took me to England, but the cemetery stayed with me. By the time I was writing my master’s thesis, I found myself in the “medical humanities” camp, where I could study literature and the history of science side by side. During my PhD, my research took a decidedly morbid turn towards horror, madness, and death—as did the novels I wrote alongside it. I’m a hybrid creature myself, somewhere between artist and scientist, which must be why death and its memorials still hold me in thrall: Nowhere else are cold medical fact and the warm human soul so closely entwined.

I have wandered through more churchyards now than I can remember, in places as far-flung as Edinburgh, Transylvania, and the desert Southwest. As a novelist, I’m still exploring how we put the dead to rest—or don’t. But I’ve grown up since that freshman year. I’ve lost a few loved ones of my own, to time and to illness and to overdose. I met death myself in the winter of 2023, when my health was in freefall and my heart suddenly stopped, leaving me dead on the table for more than a minute.

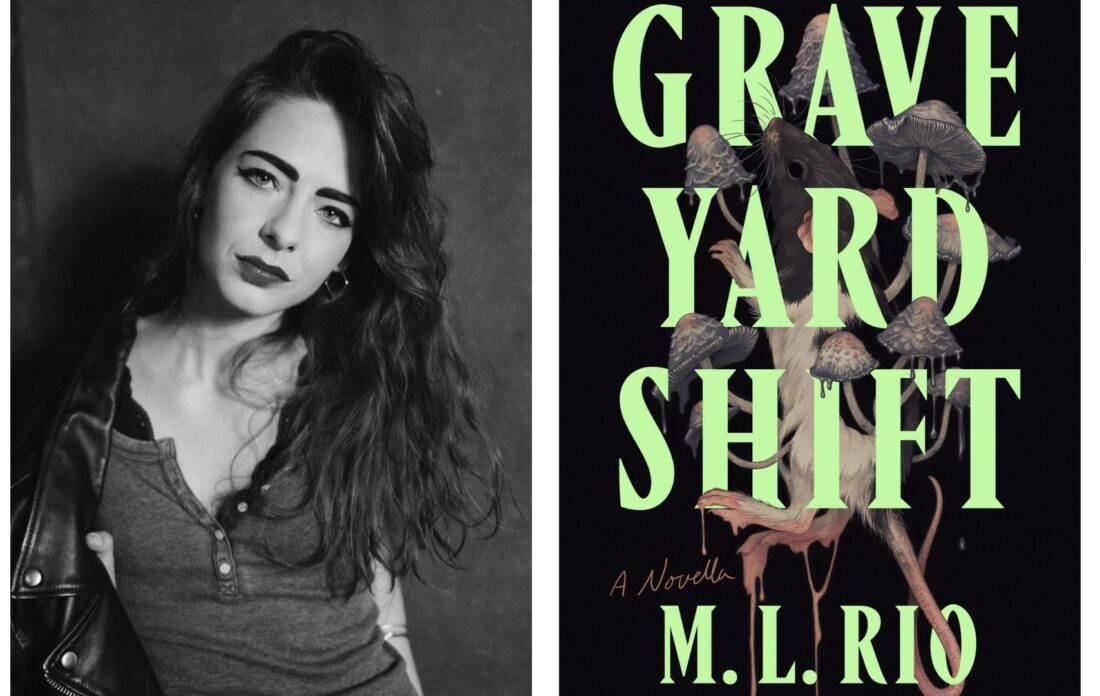

Maybe that’s why I keep flirting with mortality in fiction. The centerpiece of my first novella, Graveyard Shift, is, of course, a cemetery—where more than just bodies are buried. The five people who meet behind the church for a cigarette every night find a fresh grave that shouldn’t be there. As they try to uncover who dug it and why, one by one they find that death is much closer to the surface of life than they realized.

I return to Chapel Hill these days acutely aware of how we’ve both changed. There’s a Target now where there used to be nothing but old brick buildings. Many of my old haunts have closed their doors for good. Most of my mentors have retired and become colleagues and friends. When I walk through the halls of the CDC, show posters I designed a decade ago hang alongside photos of students I don’t recognize, who seem impossibly young.

But the Old Chapel Hill Cemetery is always the same, reassuring in its permanence. Whenever a book tour brings me back, I park in the same spot I always did and take a long walk between the tombstones or just sit in silence for a while with my old friends. All the plots have been purchased now, the places claimed. But I’ll keep coming here to rest, so long as I’m alive.

M.L. Rio holds an MA in Shakespeare studies from King’s College London and Shakespeare’s Globe and a PhD in English from the University of Maryland, College Park. Her best-selling first novel, If We Were Villains, has been published in twenty countries and eighteen languages. Graveyard Shift is her first novella.

Garden & Gun has an affiliate partnership with bookshop.org and may receive a portion of sales when a reader clicks to buy a book.