It’s tough to build a rocket, as NASA demonstrated again on January 16, when the four engines of its Space Launch System’s core stage went through what was billed as the Green Run series “hot fire” at the agency’s test facility near the Mississippi Gulf Coast. The Green Run refers to the eight-step testing series before the rocket’s unmanned test flight around the moon and back, while top-mounted with the Orion capsule, in a year’s time, the first mission in the Artemis program. Hot fire signifies the first time that all four engines in the core stage have been fired at once. Put another way, this was the first hot fire test of many in the next few years, prior to the Artemis I, II, and III moon missions.

Evincing the world-weary practice of rocketeers throughout history, NASA bigs had given the ambitious test, a firing that was hoped to last up to 475 seconds (or just under eight minutes), a fifty-fifty chance of success.

Those turned out to be overly generous odds. On the chosen crystal-clear Saturday afternoon just outside Bay St. Louis, the Green Run hot fire was hot alright, just for not as long as had been hoped. The engines roared dutifully to life above the test stand’s so-called fire bucket—the heavily insulated chamber rigged to channel and ameliorate the burn with an immense flood of water. The tail flames were so intense and the resulting steam cloud so enormous that it formed rainbows as it rolled out into the otherwise blue sky over Mississippi’s bayou country.

But every bit of the deep rocket magic—the mighty blaze, the Zeus-like rumble, and the wild play of rainbows— vanished just a few seconds past the one-minute mark. As the NASA presenter noted, the deer grazing in the savannah just a few hundred yards from the test stand didn’t even bother to scatter.

Specifically, the burn ran for 67.2 seconds before being shut down automatically by the onboard flight computer when a test parameter for the hydraulics system on Engine 2 exceeded its limit. Engineers had just begun “gimballing” or testing the engines’ steering, a key hydraulically controlled method for maintaining the rocket’s balance at launch and in flight. Had it been a launch, the parameter would have been more liberally set, and the launch would have proceeded.

NASA’s currently deciding whether to keep the stage for further, more intensive testing in Mississippi, or to barge the 212-foot-long monster around the top of the Gulf to its launch base on the other side of Florida at the Kennedy Space Center and test it less extensively there. In short, it’s back-to-school time, a circumstance with which NASA and literally every other rocket maker in history has been well acquainted.

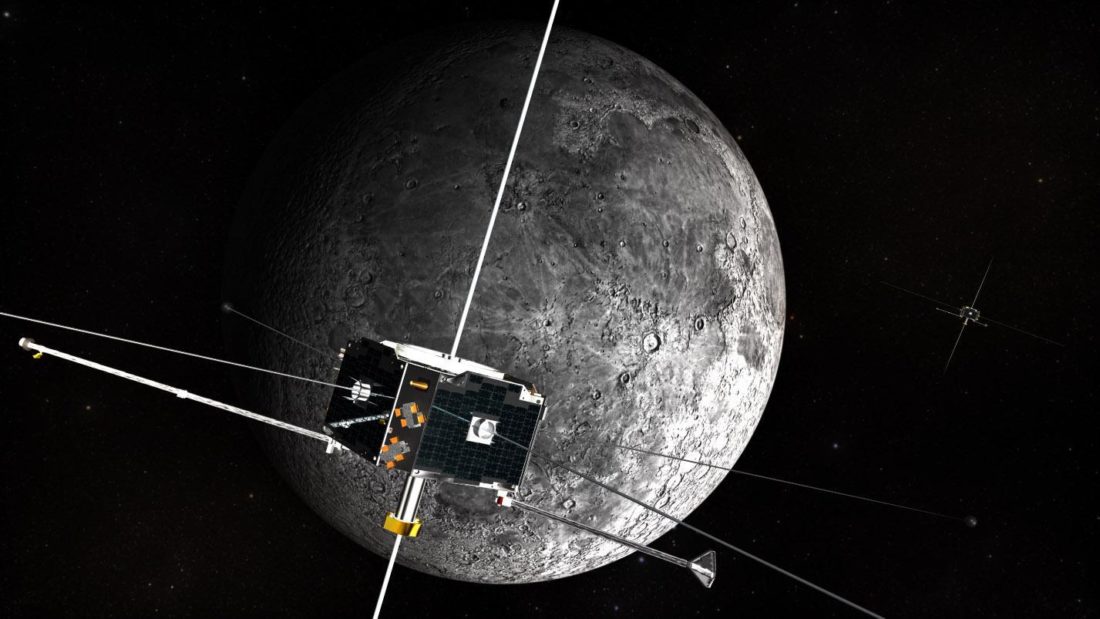

But this bump in the road won’t change the goals of the Artemis program or the larger purpose of the SLS rocket. Put in landlubber terms, the SLS is America’s own herculean long-haul intra-solar-system sixteen-wheeler. Its immediate mission is to put the first woman and the next man on the moon, and along the way, haul the components of a permanent research post the quarter-million miles to our largest and most fun satellite. In short, this century, NASA’s going big: To get to Mars, we’re first going to build a small deep-space village on the moon. The grander strategy is that the moon village, so to speak, will be the testing facility for our astronauts preparing for the bigger jump to Mars.

As ever, the lion’s share of that immense amount of design/build/test work will be done in the South. It’s not a mystery that NASA’s presence in the South is large—we’ve tossed up whole fleets of rockets over the decades from Kennedy, and Houston’s Mission Control is legend. But NASA’s Southern installations have only grown in national importance in the seventy years since Hitler’s former rocket scientist, Dr. Wernher von Braun, emigrated to America with his team and was given offices at the Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, Alabama, home of the U.S. Army’s missile program.

Today, six of NASA’s ten field centers are in the South, and—as were the Saturn and Apollo programs back in the 1960s, as well as the Space Shuttle program and much of the current International Space Station work—the massive SLS/Artemis program is largely being run out of Dr. von Braun’s former Huntsville, Alabama, HQ.

The U.S. Air Force announced in mid-January that Huntsville will be the headquarters for the Space Command, which is responsible for defending U.S. interests in the domain of space—a logical move, since America’s military rocket programs have historically come from the U.S. Army’s Redstone Arsenal design bureau, also led back in the day by Dr. von Braun. The historical reasons for NASA’s dependence on the South go back further than Dr. von Braun’s celebrated arrival in Huntsville, though, to the warm-weather U.S. Army Air Force flight training across the Sunbelt between World Wars I and II, but most intensely, in the runup to WWII. The military’s move to the South and to the West was mainly meant to take advantage of the Sunbelt’s mild winters, which dramatically accelerated the curve of the pilot training in the rash onset of the Second World War. The war also led to the expansion of the South’s many infantry bases, of which Dr. von Braun’s and NASA’s subsequent station, Redstone Arsenal, was one.

Deeply engaged in our current Artemis moon shot will be NASA’s four ruling field centers: Huntsville (administration and design), Mississippi’s Stennis (testing), Kennedy (launch), and Houston (mission control). The Artemis SLS core stage was assembled in NASA’s Michoud facility in New Orleans—which, like Kennedy and the Mississippi testing facility, is also strategically reachable via NASA’s special rocket-toting barge. It means that the South’s greater aquatic assets, the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean, are, rightly, part of NASA’s tactical playbook.

The larger point is that the South was the crucible for the world’s space race. Seventy years on, with all that military and scientific DNA in place, when comes time for America’s Mars run later this century, that grand effort will be staged and orchestrated in the only place in the country that it could be done, down home.