The Sundance Film Festival, which recently wrapped up in Park City, Utah, is one of the premier opportunities for budding filmmakers to showcase their movies to studio executives in hopes of wide distribution. This year, three documentaries celebrating seminal Southern artists premiered at the festival, and though they spoke to different genres and periods in American politics and pop culture, the films had a common thread: a story of struggle and activism, channeled through the arts. A look at the trio of films and how to see them next:

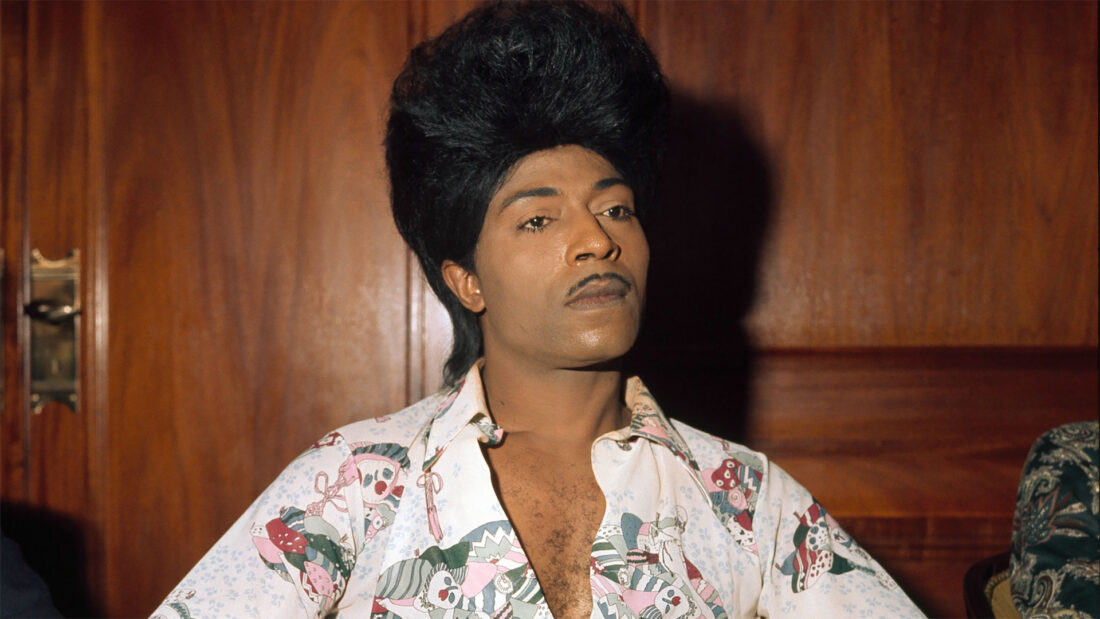

Little Richard: I am Everything

In this documentary directed by Lisa Cortes, one of the artist’s former bandmates says, “He was flamboyant, but it was always in the name of Jesus.” That line gets to the core of the film, which chronicles the Macon-born rocker’s career performing on the 1950s Chitlin’ Circuit, touring throughout Europe, and inspiring the likes of James Brown, the Beatles, Prince, and the Rolling Stones. It goes beyond celebrating hits such as “Long Tall Sally” and “Lucille,” showing the racial and religious tensions masked by the mirror suits and pompadour—how he fought to keep his music from being stolen by white artists such as Elvis Presley, who paid him no royalties when he covered “Tutti Frutti”; how his music served as a unifier when white teens would sneak into his segregated Black shows.

The film also looks at his lifelong struggle to reconcile the fire-and-brimstone teachings he learned in church with his sexual orientation and love of performing music. By the time he died in 2020, five years after the Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage, he was on the televangelist circuit denouncing homosexuality and rock and roll. Yet in the documentary, Billy Porter and one of Little Richard’s friends, Sir Lady Java, credit him with paving the way for them to live their truths.

The film was acquired by Magnolia Pictures, and the company plans to release it in April.

Going to Mars: The Nikki Giovanni Project

Nikki Giovanni was born in Knoxville, Tennessee, in 1943, and by the time her poems swept through the American imagination, the civil rights, Black Power, and womanism movements were rattling the souls of Black folks with proclamations about enfranchisement, beauty, and creativity. In Going to Mars, directed by Joe Brewster and Michele Stephenson, Giovanni looks back on her life and confronts the inevitability of aging while she also dreams of a Black women’s utopia in outer space. Anchoring the film are interviews with Giovanni, her partner, Virginia Fowler, and her son, Thomas Giovanni, along with unseen footage from her infamous conversation with the writer James Baldwin. As the narrative unfolds, it’s clear that space exploration is the only means Giovanni sees to escape from misogyny, racism, and an unhealed relationship with her abusive father.

The film’s title comes from Giovanni’s poem “Quilting the Black-Eyed Pea (We’re Going to Mars),” in which she writes: “One day looking for prejudice to slip…one day looking for hatred to tumble by the wayside…one day maybe the whole community will no longer be vested in who sleeps with whom…”

Sex and love are at the center of Giovanni’s work, which was revolutionary at a time when Black women were expected to be quiet about their feelings toward men, women, and themselves. Fowler, a scholar of Giovanni’s work, and Giovanni have been together for more than thirty years, and in the documentary, they don’t directly discuss any challenges they may have experienced as a mixed-race, same-sex couple. But the poet characterizes her relationship with Fowler as a safe place, a notion that fits the film’s theme of searching for a refuge and freedom.

The film won the grand jury prize for documentary at Sundance and is expected to be released later this year.

The Indigo Girls never set out to be activists, but their community needed them. In the late 1980s, when the duo—singer-songwriters Amy Ray and Emily Saliers, both from DeKalb County, Georgia—released their first rock album, being out in music was an anomaly. Early interviews show talk-show hosts and reporters prodding for gossip about their relationship status and how they became gay. In It’s Only Life After All, which takes its title from a line from their 1989 hit “Closer to Fine,” director Alexandria Bombach splices Ray’s own archival footage (she had a habit of carrying a camcorder on tour) with interviews with the band and their fans.

Over their thirty-five-year career, the Indigo Girls have partnered with organizations such as Greenpeace, Honor the Earth, GLAAD, and the Human Rights Campaign, advocating for LGBTQ+ rights, conservation, and women’s rights. The documentary demonstrates how their activism offstage became just as important as their music, though there’s plenty of Indigo Girls songs woven in.

Keep an eye on the Multitude Films website for details about the documentary’s release.