Her frame looks like four Popsicle sticks jammed into a marshmallow. She commands attention due to her great height and awkward body composition. She is fluffy and top-heavy, gangly and unsteady.

“What type of dog is she?!” they ask. They all ask.

June Bug is a mutt, but I decided to make up a breed for her, something illustrative. Her face resembles that of a golden retriever, but her lineage is actually a mix of, in descending predominance, Siberian husky, Great Pyrenees, and rottweiler. She is stubborn like the first, independent like the middle, and aloof like the last. For her, it’s a nearly feral combination. She’s an Appalachian Golden Wolf, I say.

While Appalachian Golden Wolves—as I have observed and classified them—are gruff, outdoor creatures, they are also sweet, playful, and great with kids. They prefer to be in the wild, but near people. There are very few places that give both of us the lives we want, something that became apparent shortly after I adopted June from the Lexington Humane Society eight years ago, back when I was living with my mother in a four-bedroom rental house on a Kentucky horse farm.

The acreage at the farm provided a comfortable buffer between a puppy and any threat of danger. Within a few weeks, I began leaving the sliding door open for her to come and go from the yard as she pleased. During her first year, she grew to the height of a Shetland pony, and her tail erupted into a white plume. She rarely came inside, sprawling out in the grass to watch the sun set in the late afternoons. We developed a workable rhythm, her lumbering outside during business hours and me joining her out back for a drink after shutting my laptop for the day.

June was happy in Kentucky, but I felt stagnant. When I received an opportunity to coach high school basketball in Asheville, North Carolina, I called her in from the farm, loaded her in my pickup, and headed south for the Blue Ridge Mountains.

In Asheville we found a cute house with great neighbors. It was there that friends and I began referring to her as an Appalachian Golden Wolf. Though the home I’d rented had a fenced yard, the fence was no taller than a park bench. June cleared it with no more effort than it took her to hop over my laundry basket. So she settled into life as an indoor dog, a domesticated dog. We spent weekends roaming through woods and swimming in rivers. She had no shortage of adventures, but they all ended up back inside. Appalachian Golden Wolves hate inside.

She offered occasional reminders, moments of resistance. Once, after a day hike in the Linville Gorge, she refused to get back into my truck to go home. It was a Sunday, a new workweek lay ahead, and we were more than an hour from Asheville. I tried singing to her and luring her with treats, to no avail. Soon it was well past sunset. Sunday night edged toward Monday morning, and when I saw the first and only set of headlights in hours, I flagged the car down and recruited one of its occupants to assist me. June tilted her head sideways as the man approached, her tail still, eyelids heavy. When he got within four or five feet, she stood up, trotted about ten yards up the trail, and flopped back down in the dirt. I decided I had to drive to better cell service to notify my boss. As I was pulling away, I looked in my rearview and saw her trotting along in the glow of my taillights. I slowed to a stop and opened the passenger door. She came closer, looked at me, and sprang up and inside. I stared at her in disbelief. She stared out the front windshield.

In the spring of 2022, after nearly five years in the same house, I decided it was time to say goodbye to Asheville. I was headed back home to Kentucky, but I had one more job to do before leaving North Carolina. I’d accepted a three-month gig as a head counselor at the all-boys summer camp I attended as a kid, thirty minutes south at Lake Summit. It provided a place to stay and meals to eat, and I could bring June. An idyllic lull between chapters.

At the lake, I shared a quiet, childless cabin with one other thirtysomething, a teacher from the Research Triangle. For the first time in five years, I could release June back into her natural habitat. She slept in the dirt beneath the floorboards of our cabin. In the quiet of the night, I could hear her running in her sleep, stirring up the dry leaves.

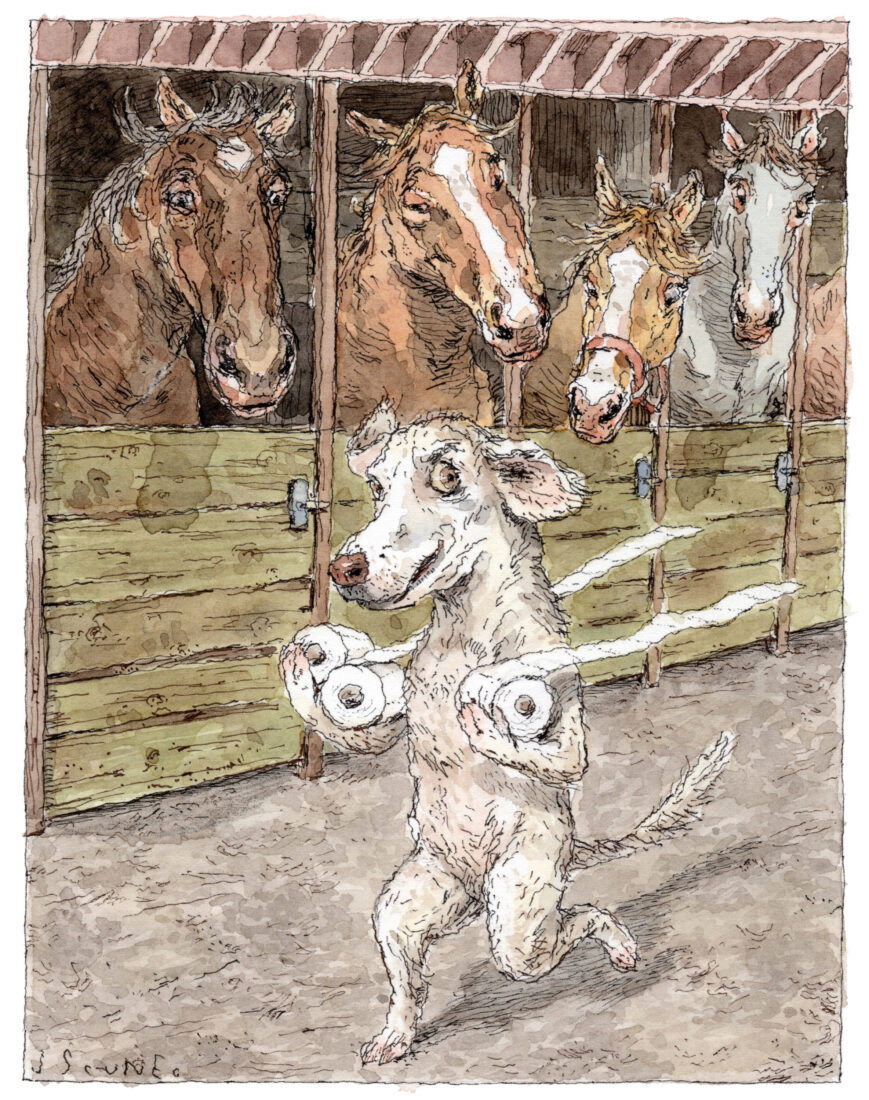

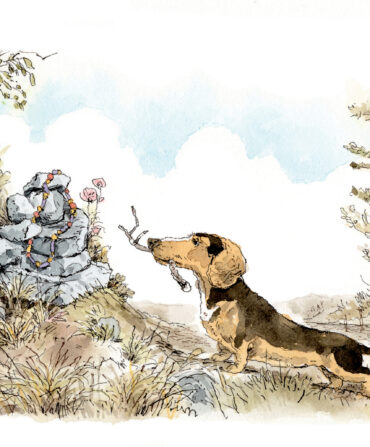

Camp dogs are magnets for homesick children. Everywhere June went she was hugged, kissed, confided in, and fed smuggled treats by scores of boys. Sometimes she needed a break and hid, but mostly she embraced her role, making her rounds to the various activity areas, only reappearing at my cabin for breakfast and dinner. A morning might see her steal the balls from the tennis court or from water baseball. An afternoon might call for a checkup on the horses at the barn or a toilet paper theft from one of the cabins. She dug holes and chased woodchucks, swam, slept, and ate manure.

As I made my own rounds to check in on the cabins each night, she followed me in and out of every slapping screen door. Squeaky children, their hair still wet from evening showers, squeezed and caressed her until their pajamas were covered in golden fur. Sometimes June found a cabin she liked, crawled under one of the bottom bunks, and stayed there.

Her boundless freedom did lead to a few incidents. Thunderstorms sent her into a panic, her only means of self-soothing to run away from the perception of danger. I got calls from homes around the lake. A woman once found her, stuck and crying, on the screened-in porch of an unoccupied house. June had pushed open the door to enter but couldn’t pull it back to exit. On the Fourth of July, amid the noise of the fireworks, she leaped from the end of a dock onto a vacationing family’s passing pontoon boat. But I couldn’t bring myself to lock her up, and with the exception of thunder and fireworks, she never left the property.

On our last night at camp, she followed me to the campfire circle, the site of our unofficial commencement—a time of reverence, songs, stories, and reflection. It is a beautiful firepit. The flames sit on a small island surrounded by a moat of clear water. Three ascending circles of stone benches ring the water like ripples, the towering pines funneling the smoke skyward. June lay down a few feet away, at her customary remove. She remained still and quiet for the duration of the proceedings. At the end, we all rose and wrapped our arms around one another’s shoulders to sing “Taps.” A last farewell to camp, to the summer.

“Day is done…”

ARROOOOOOOOOO…

“Gone the sun…”

RARAROOOOOO…

It was a howl fit for a country ballad. For six years, I’d only heard it when sirens rolled past. June would stop what she was doing, anything, and cock her head to join them. But on our final night in North Carolina, she sang with us. She joined the circle. The children’s plaintive voices broke up into giggles.

The next morning, she watched from under the cabin as I packed up my truck. The kids departed, and an eerie hush fell over the property. She knew. Too big for my half back seat, June always rides shotgun. When it was time to go, I called her name and slapped the passenger cushion. At first she didn’t move, and I feared a Linville repeat as she watched me from the shadowy pile of leaves she had drawn together into a nest. But after a few more tries, she hopped inside, planting her haunches in the seat and front feet on the floor. She propped her chin on the windowsill, perked her ears, and watched camp recede behind us.

“We’ll be back,” I said, leaning over to scratch her neck as the gravel crunched beneath the tires. We hit the northward pavement, and her ears wilted back to her head. She let out a big sigh and swung her gaze forward out the windshield. She was resigned, but not sad. I had earned her trust to find another spot, somewhere on Earth at the margin of civilization and wilderness, with enough dirt for a dog to dig and enough people for her to love.