Editor’s note: Leah Chase died in June 2019, a few months after the following article was published.

As the proclaimed Queen of Creole Cuisine, Leah Chase reigns at Dooky Chase’s, the seventy-seven-year-old New Orleans restaurant where the famous (Mahalia Jackson, Beyoncé, several presidents) and the familiar (her neighbors in Tremé who have eaten there for decades) come to dine and pay homage. But Chase is more than the sum of her gumbo and fried chicken—she embodies the city and its history. During the segregated civil rights era, Dooky Chase’s was one of the few public places in New Orleans where activists such as the Freedom Riders and Martin Luther King, Jr., could meet with people of other races. “You did things back in those days and you didn’t consider yourself changing anything,” Chase says. Now, at age ninety-five—after earning just about every honor possible, including the James Beard Foundation’s Who’s Who of Food & Beverage in America, and the Southern Foodways Alliance’s lifetime achievement award—she can still be found in the kitchen at Dooky Chase’s every day.

You say of growing up in Madisonville, across Lake Pontchartrain from New Orleans, “I guess we were the poorest things there.”

A lady called me on Sunday, and she said, “Leah, I want you to see this across the street.” And the sign on the little building said, VEGAN SOUL FOOD. I said, “Well what the heck is vegan soul food?” [Laughs.] Well, I guess that’s what I came up on, vegan soul food. I was six years old when the Great Depression came, and there was no meat—there was no meat for anybody.

You graduated from high school at age sixteen, and took your first job in New Orleans two years later.

I went to work for this woman—I had never been inside a restaurant in my life. And she put me on the floor the next day. We were selling breakfast and lunch, making hamburger sandwiches. And after that, we said, Our people are tired of eatin’ sandwiches—let us cook one meal. Now, we don’t know one bloomin’ thing about what to cook, but we all knew what we ate at home. And one of the dishes that the Creoles of color always put together when they didn’t have much money was wieners in a Creole sauce. So we called it Creole wieners and spaghetti.

But you still weren’t sure you wanted to do that for the rest of your life.

You get restless as a young person—you want to try new things. So I went to work for a bookie. I used to like boxing, too. One day my grandfather showed me a picture of Joe Louis. And he said to me, “This man can beat anybody in the world.” And I thought that was the most fascinating thing I ever heard: how strong you could be, that you could beat anybody in the world.

So you were hanging out with boxers?

You were single, but you knew how to take care of yourself. When people would say, “Leah, I want to take you out,” okay, you put on your best clothes you have, and you go out. But I’m not going with you in any dark corners. I’m going to sit at my friend’s little bar—they had plenty of women who had bars in those days. You’d sit there and you’d have a little Tom Collins and you’d talk and you’d go back home.

When you met your husband, Dooky, and started working at his parents’ restaurant, Dooky Chase’s, it was a sandwich shop.

I came in, and I said, “We’re gonna change. We’re gonna do like the folks on the other side of town. There’s no difference in people but the color of their skin.” Now, that was stupid. When you’re young, you don’t know from nothin’. I’m gonna put lobster on the menu, lobster thermidor. Well, my dear, those people called my mother-in-law and said, “That girl is gonna ruin your business. Nobody wants lobster thermidor.” They had never had the chance to eat it! That to me was the worst thing about segregation: Black people were not allowed to learn.

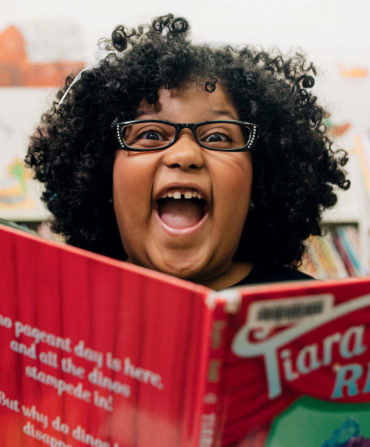

Photo: Cedric Angeles

Chase (left) and interviewer Harris at Dooky Chase’s restaurant.

Your mother-in-law believed in you, and let you start cooking gumbos and jambalayas. Everyone came to Dooky Chase’s—Ray Charles, James Baldwin…

Everybody came here because there was nowhere else for them to go. It was segregation. If they wanted to sit down to a table and eat, they had to come here.

There were no other black restaurants?

Not like this. Not with tablecloths. Dooky used to say to me all the time, “You’re never satisfied.” I think as long as you’re living, you should try to grow, try to raise yourself up. Raise somebody else up with you.

You raised three daughters. What does being a Southern woman mean to you?

Southern women have an air about them. You could be poor as Job’s turkey, but you knew you had some culture. [In my day] you learned it from working in white people’s homes, and you took what you learned to your house. We may not have all the silver they had, but you had a good piece you saved. During the week, you ate on an oilcloth. But on Sunday, you had a starched and ironed tablecloth, made of flour sacks. Your mother made you embroider the corners and crochet the edges. So you had a little culture, you had a little class. And I always say, a good woman ought to know how to talk her way out of hell if she has to.

What do you hope your legacy will be?

I was taught that your job was to make this earth better. I hope my children will carry on [Dooky Chase’s]. I hope I’ve taught them enough to keep trying to grow, keep trying to make people understand how to enjoy life. Look at all the beautiful things around you, look at the progress. You gotta enjoy that, you gotta appreciate that, and I do.

Read more from our August/September 2018 Southern Women issue