When Leyla McCalla was 10, she spent the summer at her grandmother’s home in Haiti, a world away from her childhood in New York City. McCalla’s parents were Haitian immigrants, and her mother—a lawyer—sent McCalla and her younger sister to stay with her mother while she crisscrossed Haiti doing legal advocacy work in a country that was increasingly volatile. It was a seminal experience for McCalla, but one that she hadn’t fully revisited until recently. In 2016, Duke University acquired the archives of Radio Haiti, an independent station that rose to prominence in the 1960s under the ownership of the journalist and human rights activist Jean Dominique, who fiercely railed against dictatorial control and government corruption while giving the Haitian people a vital outlet for free expression. (For more on the work of Dominique—who was assassinated in 1985—check out the exceptional documentary The Agronomist.)

Duke commissioned McCalla to create a multimedia theater performance using the Radio Haiti archives as source material. As McCalla pored through the material—which is available for anyone to access via Duke’s website—she also began to reconcile her own Haitian identity. Encouraged by the work’s director, Kiyoko McCrae, she incorporated memories of her visit to her grandmother’s into the script, and conducted her own interviews, including speaking directly to Dominique’s widow, Michèle Montas.

The resulting Breaking the Thermometer to Hide the Fever premiered at Duke in 2020, just prior to the onset of the pandemic (McCalla says she’s hoping to bring the theater performance to other markets soon).

A multi-instrumentalist and vocalist now based in New Orleans, McCalla is perhaps best known as a member of the Carolina Chocolate Drops and Our Native Daughters—her project with Rhiannon Giddens, Allison Russell, and Amythist Kiah—and will release her new album Breaking the Thermometer on May 6, a collection of songs that essentially serves as the soundtrack to the theater performance. Today, Garden & Gun is proud to premiere “Le Bal est Fini” (the party is over), one of the album’s highlights, with McCalla’s mesmerizing vocals and calypso beats over the sound of Caribbean waves lapping the shoreline.

Listen to the track below, and read on to hear from McCalla about the song, Haiti’s prominence in American history, and her own memories of the country. Breaking the Thermometer is out this Friday, May 6, and available for preorder here.

I think most people are unaware of the longstanding relationship between Haiti and the United States.

Haiti has been connected to American history for centuries. In Savannah, Georgia, there’s a monument to Haitian soldiers who fought for American independence in the 1700s [located in Franklin Square]. Haiti for years bounced between Spanish, French, and English control, but then in 1804, it completed the first successful slave rebellion in the Western Hemisphere that resulted in the first independent Black state. So, there are definite parallels.

What was most important to you when writing Breaking the Thermometer?

Haiti is a place that has been so misconstrued in the American imagination. It’s been stigmatized, and I feel that that is due to a lot of the racism in our society and in our culture. I wanted to get the story right. For a long time, I was the only Haitian collaborator, so I was balancing this insider-outsider perspective, both within the collaboration itself, but also within myself. There are parts of me that really don’t feel very Haitian or not Haitian enough to be telling the story. And part of my healing process of making this record was reckoning with my own legitimacy as a storyteller.

Your experience at your grandmother’s plays a big role in the play and album. What are your most vivid memories?

My grandmother had this compound with a lush courtyard where the walls were painted white. She got us a dog. She got us a pig. We used to feed the pig mango seeds from our leftover mangoes. I remember her cooking chickens. She was slaughtering the chickens herself, and we’d be in the courtyard just gawking at what was happening. She bought us every kind of bird and gerbil she could find at the market to entertain us. It was like Noah’s Ark. But she was also very outspoken. She really wanted us to identify as Haitian and wanted us to love Haiti. That was part of her personal mission.

What is the background to the song “Le Bal est Fini?”

In 1980, the Duvalier regime cracked down on journalists and human rights advocates. Jean Dominique wrote an editorial that basically said, “The party is over.” I just sat down with my banjo and started singing the words I heard in his editorial. Musically, I wanted it to be a party song, to have the feeling that we’re dancing into the apocalypse. The world is ending, but there’s still movement, there’s still vitality, there’s still life, and all these things are happening at the same time.

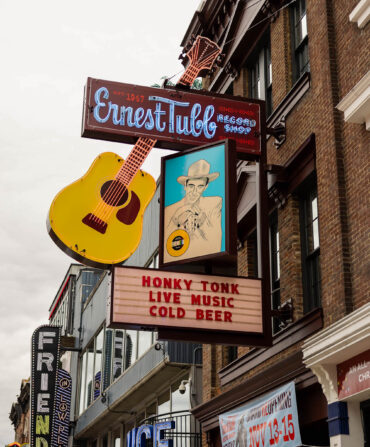

You live in New Orleans now, a city that has a significant Haitian population. Do you have any favorite places?

Fritai is a new Haitian restaurant opened by my friend Charly Pierre on Basin Street, in the Tremé. But if you want food like my grandmother made, Rendez-Vous Créole on the West Bank is where I go. It’s very over-the-top Haitian in the hospitality sense. I went there on a Saturday night, and they said, “Tell us what you want to eat. You want beer? Okay, we’ll get it.” They were literally going to the corner store to buy us beer. It was cracking me up. It felt very authentic.

Matt Hendrickson has been a contributing editor for Garden & Gun since 2008. A former staff writer at Rolling Stone, he’s also written for Fast Company and the New York Times and currently moonlights as a content producer for Ohio University’s Voinovich School of Leadership and Public Service in Athens, Ohio.