Lady Godiva is dancing as beer sloshes in its mug. She’s in the French Quarter, on the corner of St. Ann and Royal streets. Behind her stands a bulb-nosed man in what’s left of his tuxedo. Off to the side is a child, perhaps Godiva’s daughter. She’s in white boots and a majorette uniform. This young girl, quite likely the only sober person on this street corner, regards with mild interest the photographer, who is my father, Jerry Tisserand. It’s Mardi Gras in New Orleans, 1959.

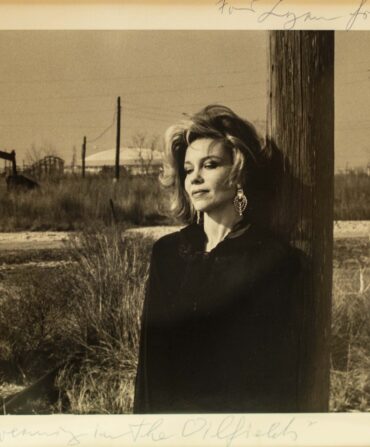

This scene showed up on a Kodachrome slide I uncovered this past year, one of dozens of photos from a trip my father took to Mardi Gras. Before seeing these pictures, I had never heard about this trip. Nor did I know that my dad, four years before he walked up to that French Quarter corner and snapped Lady Godiva’s picture, went to his Army PX where he was stationed in Orleans, France, and purchased a German Bilora Bella camera. He wanted to take photos “that no one else has taken,” he wrote to his family, and that artistic pursuit carried him across Europe, back home to parties in Indiana and Kentucky, then to Mardi Gras.

Sometime following that last trip, he put his camera down and boxed up his slides, and they apparently remained unseen for sixty years.

My dad was a lifelong salesman and stockbroker. The discovery of his photography came as a complete surprise. He died in 2008, and he left me boxes filled with everything from century-old prayer cards for relatives I can’t name to his childhood paper route schedule to the two steel boxes that contained his slides. I was staying close to home because of the pandemic, so one evening I finally started opening these boxes. As I sorted through it all, I began calling his sister—my Aunt Rosie—to hear stories of this decade of my father’s life: about the death of their mother from cancer, his homesickness while stationed in France, the wild parties they’d throw together at their grandfather’s cabin near Henderson, Kentucky. During these months of conversation, Aunt Rosie was going in and out of quarantine in her assisted living facility, contracting and eventually recovering from COVID. Perhaps because of this period of isolation and distance, we were able to deepen our connection to each other.

There were many revelations in our conversations as well as in Dad’s boxes, but nothing shocked me more than the scenes from Mardi Gras.

Dad enjoyed New Orleans and after I moved to this city, he had visited often. He loved nothing more than a long lunch at Liuzza’s on Bienville street followed by a dish of lemon ice at nearby Angelo Brocato. Back then, I’d show my dad pictures of my family’s Carnival costumes. I still marvel at how not once over those long meals did he tell me about his own Mardi Gras adventure.

Equally surprising were the subjects of Dad’s photos. There are a few expected shots of Canal Street parades, and of his friends getting coffee at Café du Monde. But when Fat Tuesday dawned, Dad grabbed his camera and headed away from the thickest crowd, deeper into the Quarter. There, he took photos that are filled with all of the friendliness and wonder that I associate with Carnival at its finest.

The photos are even more wondrous because many of them capture gay Carnival at a time when, as historian Howard Philips Smith documents in his essential book Unveiling the Muse: The Lost History of Gay Carnival in New Orleans, being outed could have devastating social and economic consequences. It was Mardi Gras, but in the words of the singer Pete Seeger, it was also the Frightened Fifties. The moments my dad captured were as much scenes of defiance as of debauchery.

Hoping to learn some of the stories of the people in Dad’s photos, I contacted Smith, as well as the historian Wayne Phillips, and I posted the shots in social media groups to see if anyone recognized them. One of the costumers, seen in 1959 in an under-the-sea costume with angel fish and seahorses, shows up in a home video from 1954, dressed just as elaborately with tentacles sprouting from his crown. But I learned neither his name nor the names of anyone else.

So it is up to the pictures themselves to tell the tale, the revelers’ stories written across the costumes they adorned that morning, with my dad joining in the day’s fun and then keeping these photos safe through the years. Thanks to him, these images have survived to ask a question that is posed every Mardi Gras: Why spend time trying to solve a mystery when it presents itself to you so spectacularly?

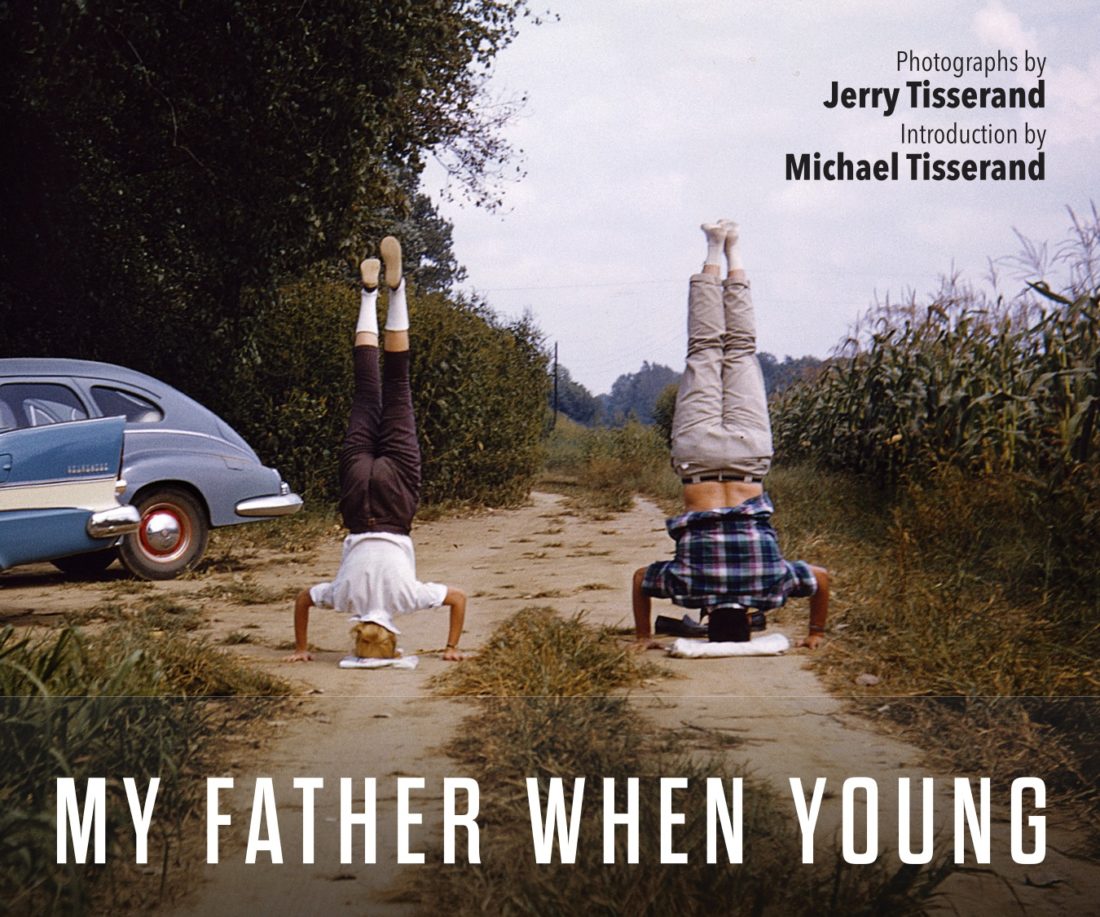

My Father When Young: Photographs by Jerry Tisserand will be published in May 2021. Click here for more information on the forthcoming book.