Nick Laracuente was driving through rural Millville, Kentucky, one foggy morning in 2008 while on a honeymoon road trip with his bride, Tiffany, when he crested a rise and saw the turrets of a limestone castle break through the mist. “It looked like something out of a horror movie,” Laracuente says. Laracuente had stumbled upon the Old Taylor Distillery, a local landmark built by Col. E.H. Taylor in 1887, abandoned for decades, and recently reinvented as Castle & Key distillery. He didn’t know it then, but both bourbon and Col. Taylor would soon play a significant role in Laracuente’s archaeological career.

Photo: Courtesy of Nick Laracuente

Nick Laracuente at work.

Born on an army base in Wurzburg, Germany, Laracuente moved often as a child, living in at least a dozen locales before his father retired while based at Fort Knox, Kentucky. His mother is a Kentucky native, and Laracuente has always considered the Bluegrass state home. He graduated from Tulane University in 2003 with a degree in archaeology and spent several years surveying old plantations in Louisiana for the National Park Service. He then investigated the impact of historic weather events on Florida’s Spanish missions for his master’s thesis. Wary of the esoteric and transitory life of an academic, Laracuente and Tiffany moved back to Kentucky, where he currently works for the Kentucky Heritage Council. One day a neighbor mentioned that Canada Dry once produced a Kentucky-made bourbon, which resulted in a road trip to survey several historic distillation sites, which led Laracuente to begin seeking out and documenting even more sites in his free time.

For example, in 2014 the record of a bitter lawsuit led him to the Jack Jouett House Historic Site in Woodford County. Jouett is famous for riding to warn Virginia Governor Thomas Jefferson of approaching British troops during the Revolutionary War. He also operated a distillery, which he sold to a neighboring family for 1,400 gallons of whiskey. The family never paid, and the two parties feuded in court for nearly a decade. “In all of those documents, while they’re calling each other drunks and liars and whatever, they include details about the distillery,” Laracuente says. “We were able to use those landmarks to figure out exactly where the distillery was.”

The biggest find in Laracuente’s archaeological career is the one that led him back to Col. Taylor. In 2016, a work crew was renovating a nondescript storage area at Frankfort’s Buffalo Trace Distillery into an event space when they punched through a concrete floor and heard rubble tumble into a void below. Distillery representatives called Laracuente to check it out. Further investigation revealed a mishmash of ornate pillars and remnants of walls, along with large, brick-constructed fermenting vats that had once been lined in copper. Working from an old fire insurance map, lithograph drawings and clues revealed during a year-long archaeological excavation, Laracuente helped piece together the story of what’s today known as “Bourbon Pompeii.”

Photo: Courtesy of Nick Laracuente

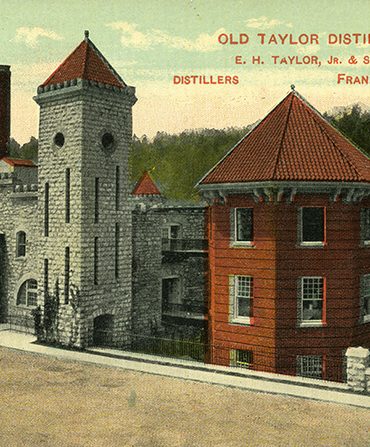

A look at the Old Taylor Distillery before the restoration.

In 1860, Col. Taylor had purchased a defunct distillery on the site, tore it down and built a larger, more modern operation. That building was struck by lightning and burned to the ground a decade later, and Taylor used the insurance money to construct an even larger operation, the O.F.C. Distillery. “He rebuilt it within a year, so he didn’t have time to clean it all up and make a clean surface,” Laracuente says of how the ruins of three distilleries were buried and forgotten.

Laracuente has since gained a degree of notoriety. He’s featured in the documentary NEAT: The Story of Bourbon and has presented at the New Orleans Bourbon Festival, among other events. But it’s his 7-year-old daughter and occasional field companion, Rosemary, who succinctly distills the essence of his work. “I like the things, but it’s more cool learning the stories about the people who used the things,” she once told her father. “I had tears in my eyes I was so proud,” Laracuente says. “It’s more than just the bourbon—there’s a story behind every bottle.”