The Southeast is home to more salamander species than anywhere on the planet. Though the amphibians fly under the radar due to their small size, nocturnal habits, and tendency to spend time below ground, more than a hundred different kinds of salamander are found across every nook and cranny of the region. Some, like the two-foot-long hellbender (nicknamed the “snot otter”), are fully aquatic and breathe through their skin. Some are blind and live in caves, while others frequent the forest floor. And now, there’s a new species to add to the list.

Engineered perfectly for life in the crevices of rocky outcroppings, the newly discovered Hickory Nut Gorge green salamander is named after the only place in the world where it’s found—North Carolina’s Hickory Nut Gorge, a fourteen-mile-long canyon that cuts dramatically through the Blue Ridge Mountains half an hour southeast of Asheville. If you don’t know where to look, you might never spot one, and even if you do, it’s a search—one that Chris Wilson, a wildlife ecologist and conservation scientist and an author of the paper describing the new species, knows well. “You spend hours crawling up steep hillsides through rhododendron thickets, then straining to peer into dark rock crevices with a flashlight,” he says. “You see lots of crickets and slugs and sometimes snakes or bats. Then occasionally you see that glint of light from the salamander’s eyes staring back at you.”

Relying on adhesive toe pads and a dexterous tail for climbing, the Hickory Nut Gorge green salamander blends seamlessly with moss and lichen. With its startling green color, slender body, and large eyes, it’s one of the most beautiful and rare salamanders to grace the Appalachians. J.J. Apodaca, the paper’s lead author and the director of conservation and science at the Amphibian and Reptile Conservancy, says these salamanders “are as rare as hen’s teeth out there, but as soon as you see one peeking out of a crevice, it’s like a shot of espresso. They are just so magnetic.” The first time Apodaca saw one, he suspected it was a unique species. “As soon as I teased it out of the crevice with a tiny stick, I realized it was vastly different from other green salamanders,” he remembers. “It was compressed down with longer arms and a noticeably darker color.”

The nearest population of Aneides caryaensis’ closest relative, the regular green salamander (Aneides aeneus), lives just thirty miles away, but the researchers’ genetic analysis indicated that the Hickory Nut Gorge green salamander has been developing independently for twelve million years. For a dose of perspective, the rabbits we know today have been developing for two million, and red wolves for forty thousand. Humans sit at a brief four hundred thousand years. For Wilson, “looking at these lineages of the green salamander is thrilling. You’re among the first handful of humans to see a story that’s played out over millions of years.” And besides, he adds, “it’s on every biologist’s bucket list to play a role in discovering and describing a new species.”

Though salamanders may not be the most visible animal, they are the most abundant vertebrate in Southeastern forests, and they play an integral role in our ecosystems. “They hold the food chain together,” Apodaca says. “They are the link between invertebrates and vertebrates.” While some species are still widespread, many are under threat. The amphibians are sensitive to temperature changes, and given their highly specialized populations, habitat loss is also a pressing concern.

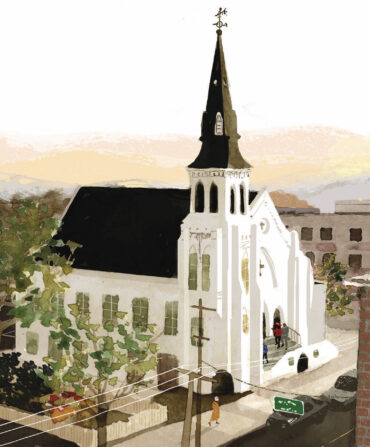

Wilson and Apodaca both work with landowners to educate people about what’s on their land and how to minimize impacts on wildlife. In the case of the Hickory Nut Gorge salamander, Apodaca and the group Conserving Carolina helped a convent of nuns put the majority of their property under a conservation easement. “They were very interested,” Apodaca says, “but what we connected on was spirituality and protecting the place because it represented something special.” And the researchers hope more people will rally around these fascinating—and ancient—creatures. “Folks in the South are really proud of their heritage,” Wilson says, “and this is our heritage.”