The man and I drove all day through the Shenandoah Valley and entered the Blue Ridge by sunset, finding the turnoff only after dark. We serpentined into the mountains until our cell service slipped, until we were singing along to a station tuned to silence. The road to Cashiers ambled through low wet forest, skirted sheer drops that whispered in the darkness of falling water. At the end of it, there was a hedge, a gate, an old fellow in a rocking chair to nod to, then a fireplace roaring on a screened porch, a tumbler full of Scotch. I fell asleep to the sound of tree frogs, woke up in a pool of sun. It wasn’t until I looked out at the view—a cliff reaching, sheer white, above the tallest trees—that I realized I’d been here before.

That before was far away and cut to pieces: a log cabin, a dirt road that just kept rising. Four years old, in corduroy overalls, I trundled up the mountain, a parent in each hand. Above us, Whiteside rose, one of the highest cliffs east of the Mississippi. I’d been promised peanut butter crackers and falcons at the top, but what I really wanted was a piggyback ride. When I discovered one was not forthcoming, I whined, stomped, cried. Did some good old sitting in the dirt. Finally, I just had to lie. “Daddy,” I said, deadpan, “I’m having a heart attack.”

I got my way.

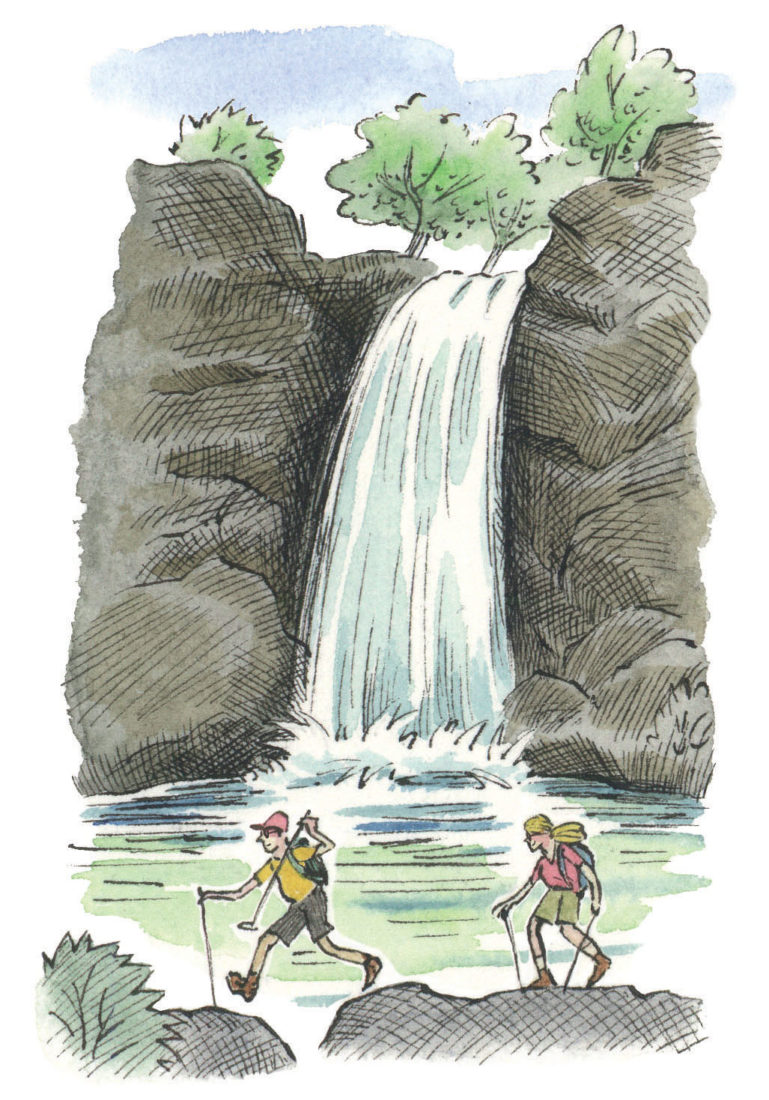

That second summer, two decades later, the man and I hiked ten miles a day, to waterfalls and iron bridges, through rhododendron thickets and forests of wind-gnarled red oak, up to peaks where falcons spun, as promised, in air as thin as lead crystal. The summer after, he and I followed the sound of water to the Chattooga’s narrows, where the river cuts deep into its granite bed, its full volume forced through a channel a few feet wide. The next year, married, we went back and stood naked as babes in the icy rush, marveling at geologic time.

Morgan C. Babst

For twelve years, we’ve spent July in the mountains, eating tomato sandwiches and auditioning sisters-in-law on the basis of their blueberry pies (we cast the perfect one). We’ve watched our daughter grow from a sprite splashing in the mica-spangled shallows to a girl who’ll laugh right down “Bust Your Butt Falls.” Every year on Independence Day, we smoke racks of ribs in the driveway and tinker with the peach ice cream. As night falls, we climb up to the driving range and sit in a ring of Adirondack chairs, watching the mountains purple in their majesty, waiting for the valleys to explode with a million multicolored stars.

There aren’t too many places in this world you can go back to and back again, places that won’t get worn down by all that looking. This is one. In the North Carolina mountains, habit sharpens the gaze instead of dulling it. Repetition turns to rhythm as your feet tread the same paths. Thirty-three years after I sat in the dirt in my OshKosh B’gosh and claimed I was dying, my husband carried our daughter piggyback up that very mountain. At the top there were falcons and peanut butter crackers, and all the eternal promise of the wild.