There’s an app for everything these days: finding your friends, finding your lost iPhone, finding—great white sharks? Yes. Since 2012, Ocearch, a nonprofit marine-research group founded and led by Kentucky native Chris Fischer, has been tagging and tracking tiger, mako, hammerhead, and great white sharks to learn more about these creatures and garner support for their protection.

Ocearch’s team has conducted thirty-two expeditions to date throughout the world—from the Galapagos to South Africa to the South Carolina Lowcountry. On these expeditions, scientists temporarily capture a shark, then spend fifteen minutes performing twelve simultaneous tests that include examining parasites in the shark’s mouth, taking blood, and making measurements aboard their boat-turned-laboratory, before releasing the animal back into the ocean with a tag on its dorsal fin. Each tag has a five-year battery life and will alert the researchers each time the fin surfaces, giving an exact GPS location when the device breaches for at least ninety seconds.

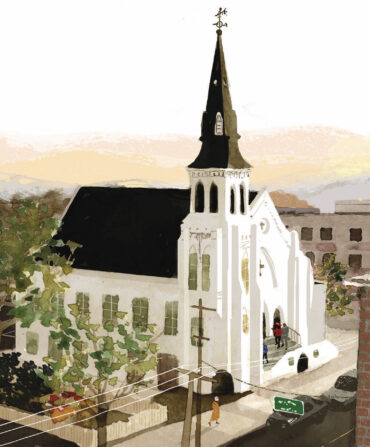

Photo: Ocearch

Lydia, a great white shark, was tagged off the coast of Jacksonville, Florida, in 2013.

Each time a “ping” is made, the Global Shark Tracker updates. And it’s not just for the entertainment of the folks who follow Ocearch’s popular website. These pings have taught scientists a lot about one of the ocean’s most important predators. “Sharks are an ancient puzzle,” Fischer says. “Before this, we didn’t even know where they went. This has showed us where sharks mate, where they give birth, and where the critical habitat areas are.”

Great whites are some of the most active sharks on the east coast, which has made them a special point of interest for Fischer and his team. Usually, these sharks are sexually segregated. Where the GPS “ping” shows males and females overlapping—on the east coast, this chiefly happens in and around Cape Cod and, to a lesser extent, Nova Scotia—that’s likely where they mate. Wherever the females are found after an eighteen-month gestation period—that’s likely where they give birth and where shark pups need to be protected. “We found out they’re mating in Nantucket and birthing in the Hamptons,” Fischer laughs. “What a life.” And like most luxury-seeking snowbirds, great whites are known to winter in the South, anywhere from Cape Hatteras to Cape Canaveral, where they cull all types of fish, squid, mollusks, crustaceans, and even marine birds and reptiles, helping maintain the ocean’s delicate balance.

The Ocearch team tagged Hilton off the coast of Hilton Head, South Carolina, last spring.

In terms of ecological stories, this is a happy one. A healthy shark population is crucial to a healthy ocean. “They’re the lions of the oceans, the balance keepers,” Fischer says. “If there are no big sharks, there are no fish sandwiches. And what cause is more important than future abundance? We need to make sure our kids can eat.”

In order to gain support for its cause, Ocearch has given a voice to and made celebrities out of dozens of sharks, like Mary Lee a sixteen-foot, 3,456-pound great white who was known to winter in Lowcountry waters before she disappeared from the radar last summer. “Mary Lee has become the most famous real shark in history,” Fischer says. Indeed, before going radio-silent, Mary Lee accumulated nearly 130 thousand Twitter followers. She also was the first shark to tip researchers to look for wintering sharks in the South. As to her whereabouts, Fischer says not to worry: he believes she’s still alive and well. “Her tracker had a five-year battery and we put it on six years ago,” he says. But she’s anything but lost forever. “Sharks repeat their migration almost exactly. Look where she was in past Julys and you can pretty accurately guess where she is [likely to be] now.”

Four Sharks to Follow:

Hilton | @HiltonTheShark

Stats: Great white, male, 12’5”, 1326 lbs

Tagged off the coast of Hilton Head, South Carolina, last spring, Hilton is well-acquainted with the east coast, having traversed it many times. He’s been known to circle Key West, venturing as far as Pensacola, and was the first shark to alert researchers about the mating site in Nova Scotia.

Lydia | @RockStarLydia

Stats: Great white, female, 14’6”, 2000 lbs

First tagged off the coast of Jacksonville, Florida, Lydia also goes to Canada to mate. And in 2014, she was the first shark ever recorded to cross the Atlantic. Lydia has traveled more than 46,000 miles since she joined the team in 2013.

George | @GWSharkGeorge

Stats: Great white, male, 9’10”, 702 lbs

Lydia may have done it first, but George is doing it now—and may go farther. His most recent “ping,” on July 13 of this year, was far out in the northern part of the Atlantic Ocean, almost to the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. “We’re very interested to watch him,” Fischer says. “It’s possible he’ll be the first shark we’ve seen to go all the way to Europe.”

Miss Costa | @MissCostaShark

Stats: Great white, female, 12’5”, 1668 lbs

“Am I pregnant?” Miss Costa the shark recently tweeted. “That’s a personal question!” And not to pry, but Fischer and the Ocearch team think she might be. Currently, she’s looping farther than usual into the Atlantic, last “pinged” far from shore in June. Watch for the official pregnancy announcement this fall: if she doesn’t circle back toward Nantucket to mate, they’ll know she’s getting ready to have her babies.