In 1959, the record “The Enchanted Sea” by the Islanders hit the charts. I was eight, and that was the summer I began going to Calvert County, on Maryland’s Western Shore. I became obsessed with the song, which, oddly for a hit record in the same summer as “What’d I Say” and “(’Til) I Kissed You,” was an instrumental, and not one that I could bop to. I associated the eerie, somewhat cheesy music—buoy bells, lapping waves, high-lonesome whistling, and mournful guitar—with the Chesapeake Bay and its vast and ancient loveliness. There, I felt a sense of time and timelessness, and longing—new feelings for an eight-year-old.

My parents had divorced not long before then, and my young mother, brother, and I started tagging along with my aunt, uncle, and cousins on day trips to Calvert County, specifically the tiny communities of Long Beach and nearby Flag Harbor. We’d leave our suburban Washington home at the crack in my mom’s ’57 Fairlane 500, traveling through downtown on Pennsylvania Avenue (way before the Beltway) to Upper Marlboro, with its huge tobacco warehouses, pulling over at Largo Road, an intersection where we’d stop at the bait shop to buy bloodworms and Honeymoon ice cream. In an hour and a half, past endless tobacco fields, we’d be at Flag Harbor. We’d spend the day crabbing from the rickety docks, fishing for spot off the rock jetties, and swimming at the water’s edge. At dusk, we’d pile back in the car, sandy and sunburned, still in bathing suits, sleeping in our towels on the backseat.

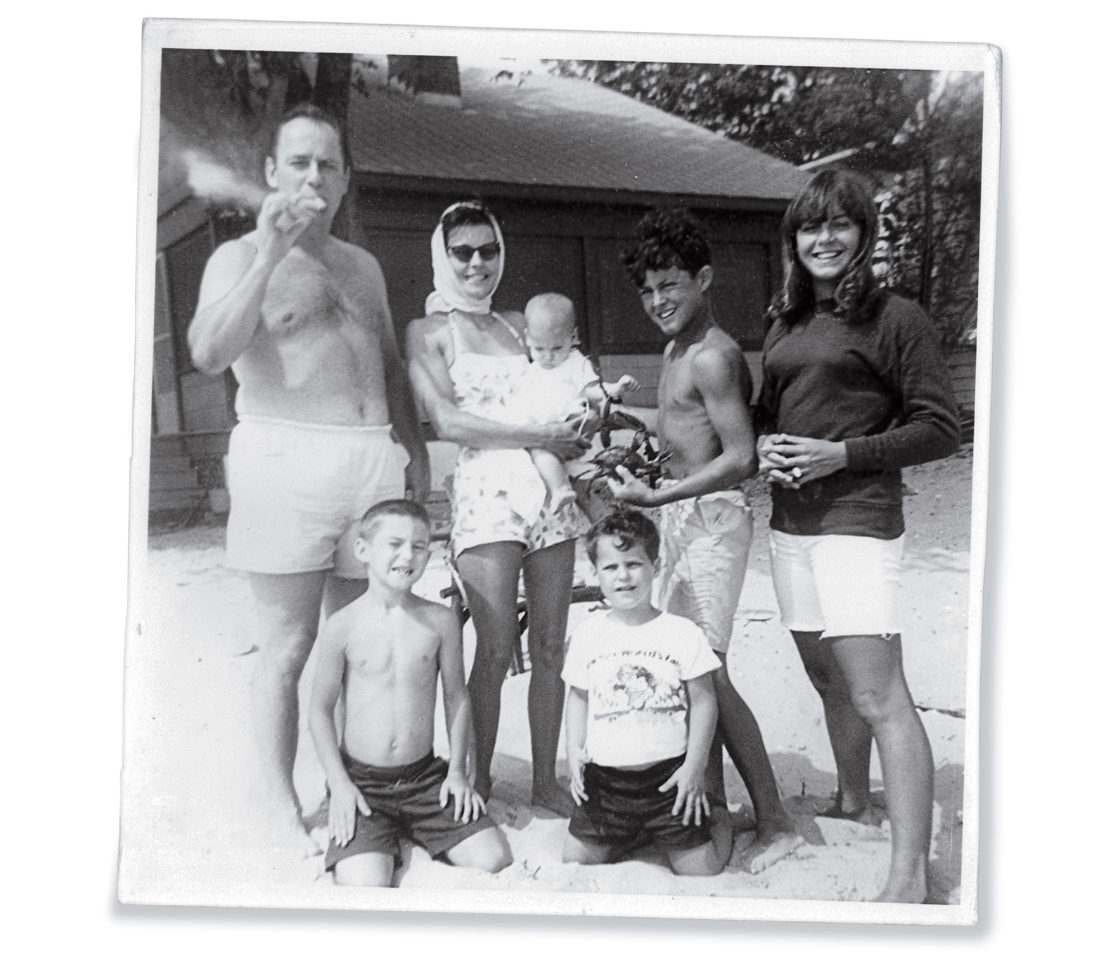

Photo: Courtesy of the author

The author (far right) and her family in Calvert County during the summer of 1967.

Calvert County occupies a long leg of farmland surrounded by water: the Patuxent River to the west, and the Chesapeake Bay (which, picayunishly speaking, is an estuary) to the east. Thousands of years ago Piscataway Indians farmed and roamed the area’s fields and beaches. Captain John Smith explored there in the 1600s, followed by the Calverts, the barons of Baltimore, and small settlements grew: Prince Frederick, St. Leonard, Port Republic, Broomes Island, Solomons Island. These communities, and the beaches and cliffs between them, span a roughly twenty-mile area at the southern end of the county.

A few summers later, we began renting an old coral-colored cottage. The adults had the bedrooms, girls in the attic dorm, boys on whatever furniture. One bathroom—but we chirren were required to shower outside. It wasn’t long before my uncle bought a little place. Our stays became longer, more adventurous. We were able to run amok, every child’s favorite pastime—to the lagoon to see horseshoe crabs mating (dinosaur precursors, still scuttling), into the woods for box turtles and snakes, and way down the beach to the towering cliffs, striated with eons of fossilized sharks’ teeth that washed down to the shore, waiting for us to find them. My aunt, our naturalist, told us that the teeth were from the Miocene epoch, fifteen to twenty-three million years ago, when enormous sharks swam in what was then the sea. Occasionally there might be an arrowhead left behind. We played the quarter slot machines—now illegal, and no doubt illegal for children then—at Buehler’s store in St. Leonard and spent our winnings on sweets like BB Bats, Mary Janes, and Good Humors.

Photo: Mike Morgan

A shark tooth exposed by the outgoing tide.

My uncle had a sweet little fourteen-foot runabout called the Sarah Belle, the lacquered wood a deep sienna. We went out every day to fish, catching rockfish and flounder if we were lucky, but just as often spot, full of bones, and creepy toadfish and blowfish that we cussed and threw back. In the evening the good stuff would be lightly dusted with flour and cornmeal and fried. Some nights we’d buy a bushel of blue crabs, spread the Washington Post on the table, and mercilessly steam the beautiful swimmers in beer and vinegar. If we saved enough meat—very difficult—there’d be crab cakes the next day made with my aunt’s classic Calvert County recipe: a pound of big hunks, a dollop of mayo, a handful of saltines, one egg, a dash of mustard, pinches of S&P. (Now I add a smidge of Old Bay.) At dawn, my brother and cousin

might be out in the water with their nets, scooping up tender soft shells, which they’d clean, sauté in butter, and serve on toast for breakfast.

My mother eventually bought a place at Cove Point, so my children grew up going to Calvert County every summer—a fifteen-hour trek from our home in Oxford, Mississippi. There was more entertainment, but less running amok. These days, Solomons offers a host of amenities—a handful of hotels and B&Bs, bustling shops, restaurants, even a Riverwalk, and the Calvert Marine Museum, the anchor of the small community, holds boatbuilding workshops and a summer concert series. On Broomes Island, you’ll find the best crabs you didn’t catch and cook yourself at Stoney’s. The fishing and boating are still good. And at Jefferson Patterson Park, you can see where Joshua Barney and his ragtag flotilla turned back the British at the Battle of St. Leonard Creek during the War of 1812. Jousting, popular since Calvert County’s founding (and Maryland’s official state sport), is celebrated at Christ Church (1672) with an annual tournament the last Saturday in August, as it has been for 150 years.

The Cove Point house, my aunt and uncle, and the Sarah Belle are all gone now, but I still make the drive as often as I can to lose myself in that world of history and Edenic beauty. It will always be my enchanted sea. To experience its essence, walk along the beach at Calvert Cliffs State Park and look for sharks’ teeth. Watch eagles soar at Flag Ponds Nature Park. Listen to that Islanders record. I still have mine.