My grandmother used to laugh and say that a little knowledge is a dangerous thing. She mainly used that quip whenever I told her some obscure fact I’d read, like why women’s shirts button on the left. Although she’s passed on, I can imagine her saying that now about my obsession with heirloom watermelons.

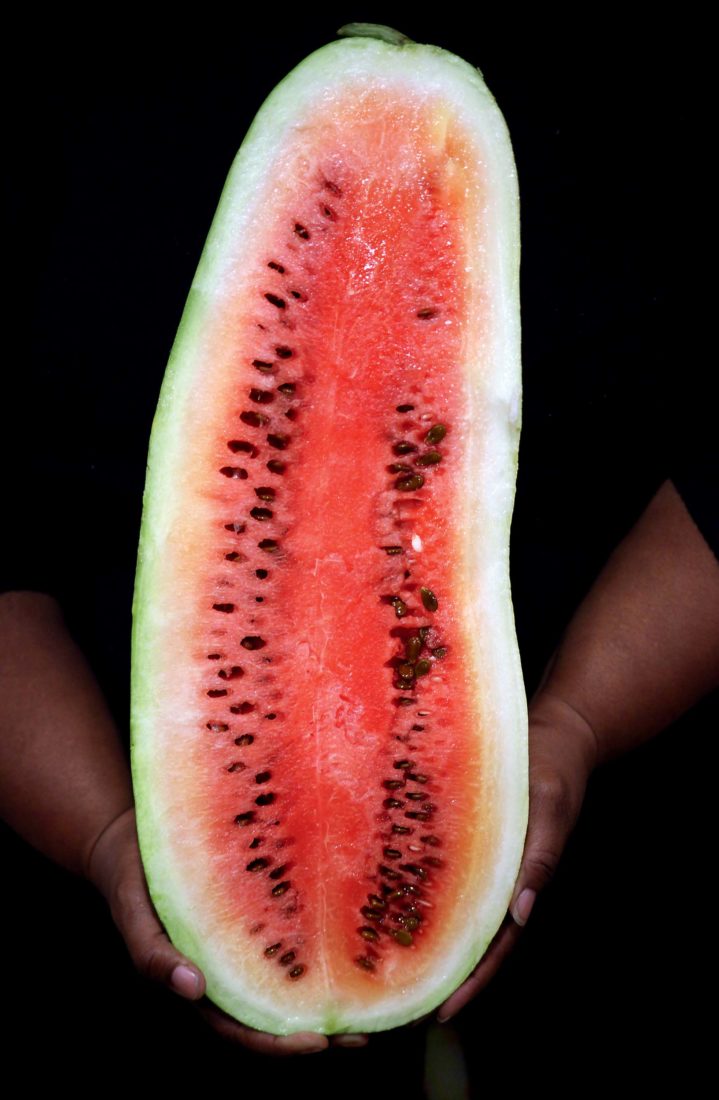

It all started two years ago after I read about the famed Bradford watermelon. Nathaniel Napoleon Bradford crossed two watermelons—the Lawson and the Mountain Sweet—to create the variety in the 1800s. By the 1860s, many considered the Bradford the most important watermelon in the South, praised for its sweetness and with a rind so soft, most of it could be eaten. Unfortunately, it fell out of favor by the early 1920s as watermelons that could ship more easily began dominating the market. But today, a descendant named Nat Bradford has revived it at his farm in Sumter, South Carolina. Early in the 2019 season, I pre-ordered two Bradford melons online and talked my partner, Joshua “Fitz” Fitzwater, into taking a road trip with me from our Richmond home to pick them up later that summer. As Fitz is a foodie, this wasn’t a difficult sell.

While waiting for our Bradfords, we started wondering what other kinds of heirloom watermelons we were missing out on. Visits to local farmers’ markets turned into weekend journeys to North Carolina to hunt down a Crimson Sweet, to northern Pennsylvania for an Ancient Crookneck, to Delaware for an Ali Baba, and almost everywhere else within driving distance. They all had variations in texture and sweetness, and after a while, we could detect notes of apricot and honey, for example, in different types. We tracked down an Odell’s White, the only commercial variety of watermelon attributed to an African American. His name was Harry, and he was possibly enslaved by William Summer, a pomologist in South Carolina (the melon’s name came from Milton Odell, who grew it in the 1850s). We shared those seeds with African American farmers in Virginia, and they were as shocked as we were to learn about the variety—and happy to plant them in their fields.

The more we tasted, the more we began to wonder why we couldn’t find any prominent varieties with distinctly Virginian roots, even though watermelons have been grown here for centuries. Of course we saved seeds from all of the melons we’d found, and we began talking about planting some the following season. Though we live in the middle of the city, the Patawomeck tribe had some land available about fifty miles north in Fredericksburg, and they were gracious enough to allow us to use a portion. We decided to plant the Ancient Crookneck, an heirloom indigenous people in Arizona had grown. We also planted the Ali Baba, which originated in Iraq; the Ledmon, from North Carolina; and the Moon and Stars, a speckled heirloom rediscovered in Missouri. Perhaps more important, Fitz began experimenting with crossing different varieties through hand pollination, including a cross we named the Double A Sweet, combining the crisp texture of the Ancient Crookneck and the sweetness of the Ali Baba.

We planted roughly sixty seeds and started making the two-hour round trip to make sure the plants were thriving, enlisting help from Fitz’s father and my daughter to add bone and blood meal, mushroom compost, cow manure, and worm castings to the soil. While tending to our plants, I played Ella Fitzgerald for them as Fitz uncoiled the solitary hose to hand water each melon, fighting off mosquitoes and heat rash in ninety-degree swelter.

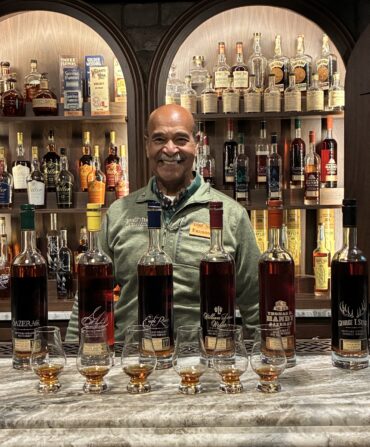

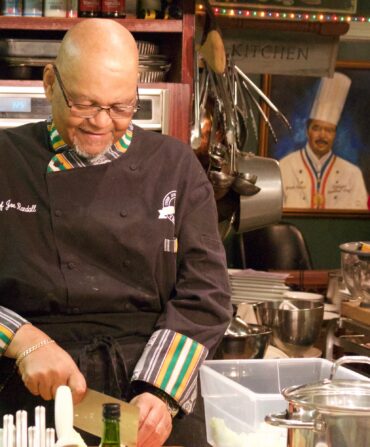

As first-time growers, we agreed that if even a handful of those seeds matured, we would count it as a win. We wound up with almost a hundred watermelons. Most grew to about twenty-five pounds, though several ballooned to more than thirty-five, and our thoughts soon turned to how best to use the ripening fruit. We brought watermelons to several Virginia chefs, including pitmaster Floyd Thomas of Redwood Smoke Shack in Norfolk and chef Forrest Warren of Smoke BBQ Restaurant & Bar in Newport News. Thomas worked them into a hot sauce with habanero and lime, and Warren into a vinegar-and-watermelon barbecue sauce, and we quickly sold the rest after a couple of Facebook posts and a tweet that went viral. Clearly, we weren’t the only ones who wanted a taste from the past.

This year, we have decided to grow heirloom watermelons once again. Fitz is replanting seeds from the best of our Double A Sweets. It takes three years for the traits to fully develop, and we’re excited to see which characteristics will carry over. And we’re now cross-pollinating three different types—the Bradford, the Odell’s White, and the Ledmon—in hopes of eventually producing another Virginia watermelon from some of the sweetest heirlooms in the South.

Over the past two years, our hobby has grown into a full-fledged passion. It was deeply satisfying to bring joy to people we had never met before. Hopefully in the first fleeting moment when they tasted that liquid sugar on their tongues, they might’ve briefly forgotten about a global pandemic while also learning a bit of Southern culinary history. And perhaps one day soon, we Virginians will have a watermelon we can call our own. My grandmother might just approve.