Pearl Fryar’s medium is plants. His message is crystal clear even among his forest of swaying green creatures, his topiary garden spread across three acres in Bishopville, South Carolina. Now in his eighties, Fryar planted his garden over decades and opened it to the public in the 1980s.

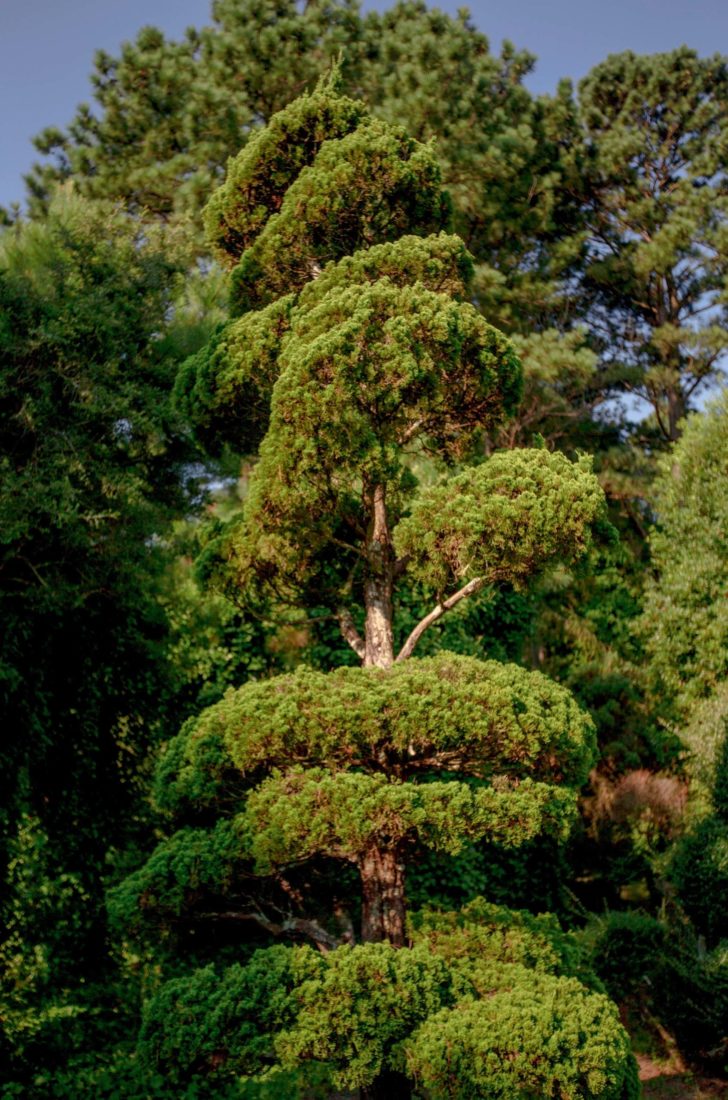

As a young man, when he worked full-time in a can factory, Fryar rescued plants from the cast-off pile of a nearby nursery, and then guided every single stem. With a chainsaw, he shaped bushes and trees into whimsical arches and curves. Fryar’s topiary garden became a local sensation, and then a national one. Over time, his abstract-art garden—and his message of love, displayed on signs throughout the yard, and voiced in interviews—brought tourists from around the world.

But as Fryar aged, the garden declined. (I’m a Southern horticulturalist and garden designer myself. Over the decades, gardens I’ve left change, grow, and sometimes die.) Easy sinuous swirls got fuzzy and sluggish. Lumps grew in branches, and sympodial sprouts went wild. Plans for saving the garden started and stopped in fits.

In March 2021, a young man named Mike Gibson returned for a visit. Gibson’s connection to topiary began when Gibson was just a little kid growing up in Ohio. “My Dad was a Navy man, like a drill sergeant,” Gibson remembers. “Every Saturday morning, he had us in the yard doing work. At seven years old, I fell in love with pruning bushes.”

“My dad was also an artist,” Gibson says. “Later, when I went to art college, painting fell flat for me. I hadn’t found my medium. But I still loved to prune. One morning, Dad saw one of my abstract-shaped bushes. He said, ‘You need to go see Pearl Fryar in South Carolina.’”

The name confused Gibson. “Who is she? Who’s this lady?” he remembers thinking. “I looked up this ‘lady’ named Pearl and what I saw blew my mind.” Fryar is a tall man, all muscle. Built like a superhero of the plant world. “I already knew about topiary artists. I thought there probably were not any black men topiary artists. I drove from Ohio to South Carolina and blew my mind again.” Gibson found a role model.

“As a young man, I’d work with Pearl each summer,” Gibson says. “Then I went back to Ohio, and I developed my own style, my own landscape business. I’d even been on HGTV, doing topiary in New York.”

In 2021, when Gibson drove to South Carolina to check in, he was shocked by the state of the garden. “I came down and found some landscapers working. They said Pearl was very sick,” Gibson says. “It’d taken him a few years to accept the help, so the garden was really in ruin. Before I even said hello to Pearl, one of the guys with hedge trimmers led me to the folks who were spearheading the renovation.” He met Jane Przybysz, the executive director of the McKissick Museum in Columbia, South Carolina, and Amanda Bennett, vice president of horticulture and collections at Atlanta Botanical Garden. “After interviews and negotiations and talking to Pearl, I became the Topiary Artist in Residence at Pearl Fryar Topiary Garden.”

Gibson and his wife and three-year-old moved to South Carolina. “With so many people and institutions involved, I hope we can reach even more children, more people,” Gibson says. “Anybody can learn topiary.”

It was meant to be. From his Dad’s inspiration, Fryar’s mentorship, and Gibson’s own need to speak to the world through topiary, the garden is on track to teach peace and love through creativity once again.

In the long run, what might happen to a home garden, a singular vision like Fryar’s? Besides all the care it needs, this garden faces big questions. How is Fryar’s vision documented and preserved? Is there a database of plants and sculptures? A guide book to living art? What sorts of plant labels identify the plants? As things die, who decides on replacement species and style? Will there be classes, weddings, or plant sales? And critically, who pays for all of that?

Volunteers from across the South have helped by providing everything from labor to loads of mulch. “We’re still in recovery mode,” Bennett says. “Mike’s the perfect person for this, and has garnered the help of so many South Carolina botanical gardeners, like the staff and volunteers from Riverbanks Botanical Garden.”

Bennett also shared a note of hope from the Atlanta Botanical Garden: “The world needs this garden, this vision,” she says. “We’re figuring all that out now. We are here for the long haul to help secure the future of this garden.”

Most South Carolina public gardens started out as pleasure gardens on plantations or were established by rich businessmen in the 1900s. Fryar’s is the only topiary garden in the country, the world, that was birthed, trained, caressed, and spoken to life with the voice of an African American man, a farm kid turned factory worker turned self-taught artist. Children once inspired by Fryar now seek their own passions. They make decisions about our world. And some, like Mike Gibson, return.

“Finding passion. That’s what Pearl is about,” Gibson says. “He spoke to every child who ever felt the world had given up on them, who couldn’t see the light. He said to them, in words and through his art, ‘You are a treasure. Find your passion, work hard at it and it will pay off and you’ll live a dream. Like I am. I know. I was one of you.’”