In 1961, as much of the world was focused on the Bay of Pigs and the Berlin Wall, 29-year-old John Cohen, then an up-and-coming photographer and musician, left his home in New York, hopped into a van, and drove south. His mission? Collect the songs and sounds of Appalachia’s old time musicians. The music he recorded on that trip—in the hollers, bar rooms, living rooms, and front porches of small Southern towns—and on the trips that followed would not only influence the course of American music but would eventually be deemed so significant that the Library of Congress would acquire his archive.

Cohen also took photographs. And those pictures, most of which have never been seen before—the negatives sat forgotten in a basement for sixty years—are now collected in a revelatory new book, Speed Bumps on a Dirt Road.

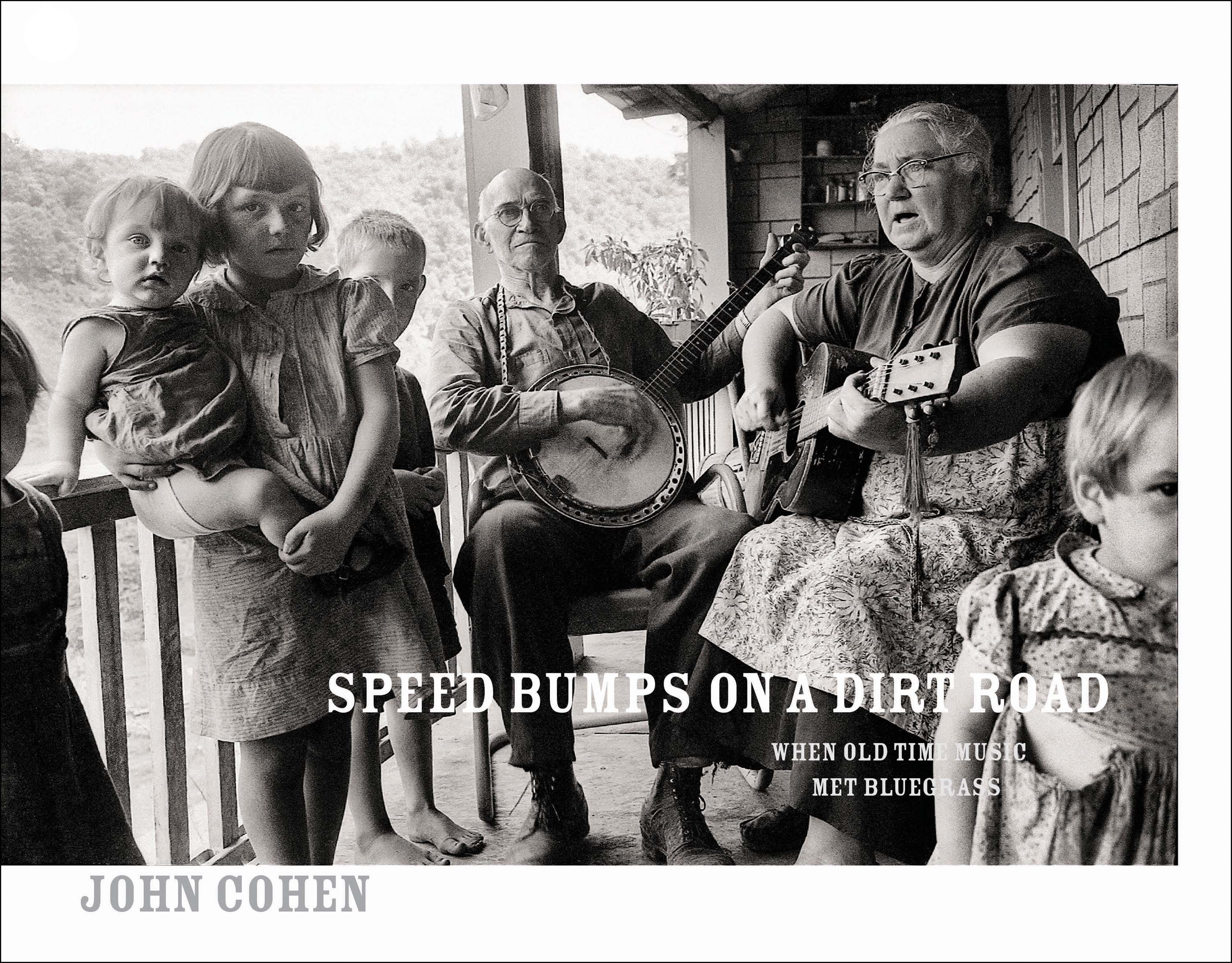

Those with an interest in old time music will find shimmering, cinematic gems here: Bill Monroe, the father of bluegrass, playing on the courthouse steps in Hazard, Kentucky; future Country Music Hall of Famers Flatt and Scruggs on a tiny stage in Iron City, Tennessee; legendary blind guitar player Doc Watson a decade before he won the first of his seven Grammys. But Cohen also captured lesser-known players, such as Pearly “Grandma” Davis, a 70-year-old fiddler who lived in Roaring River, North Carolina, in a simple home without electricity. His pictures of Davis (and almost everyone else in the book) are startlingly intimate: He shows the deep wrinkles in her face, her chair that’s missing its back, and the floor, ceiling, and walls rendered from the same rough-hewn slats. “The scene was so beautiful, so gaunt,” Cohen tells Garden & Gun. “Like a Walker Evans picture. And it said so much to me.”

Photo: From <i>Speed Bumps on a Dirt Road</i> by John Cohen, published by powerHouse Books

Pearly “Grandma” Davis and family, Roaring River, North Carolina, 1961.

The result of Cohen’s extraordinary eye for detail and atmosphere: time-capsule pictures that reveal an era when it cost 25 cents for a grandstand seat at a fiddler’s convention in Oakridge, North Carolina; when suit-wearing musicians would plop themselves down in a field to play a tune; when backstage placards reminded performers to avoid all cussing. And while Cohen would return to small-town Appalachia in the years that followed—and photos from those excursions are included in the book as well—the 1961 trip was special. “This wasn’t for a job, and there was no place to publish the pictures,” he says. “I felt free and kept my eyes open, trying to capture what I was seeing for the first time. And we uncovered some amazing musicians who were the cornerstones of the old time music movement.”

Cohen, at 87, is considered something of a national treasure himself. In addition to his becoming a celebrated photographer with pictures in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the National Portrait Gallery, the traditional tunes he collected, shared, and played went on to influence jazz greats and Jerry Garcia alike, and his own band, the New Lost City Ramblers, would perform for more than fifty years. But what’s so powerful about Speed Bumps on a Dirt Road is that it carries us back to the moment when a young man’s wide-eyed love of traditional music put him on an epic quest—fortunately, he’s brought us along for the ride.

See a gallery of images from the book here.

Bill Shapiro is the former Editor in Chief of LIFE magazine and the author of What We Keep.