We didn’t want another dog.

We being my wife and I. We’d lost our beloved yellow Lab Buddy the previous year and were still grieving, I suppose. Buddy—beautiful, superior, imperious Buddy—had been (locally) famous for eating a three-pound cheese ball and speaking in the voice of Darrell Hammond channeling Bill Clinton on Saturday Night Live, circa 1999 (we’re not the only ones who give our dog a voice, right?). But our children had been just, well, children when Buddy passed one August day. They were children still, but old enough to start demanding things. So when we moved from Florida back to our native Carolinas—trading sun and sand, which we loved, for mountains and rivers, which we knew and loved—we started looking (sort of) for a dog. It was a half-hearted search, punctuated by marathon sessions of viewing old Buddy photos (my wife and I were particularly susceptible to Buddy as a puppy: “Look at those paws! Look at those ears!”). But one day my sister called: Her hairdresser Tonya, a friend from high school, had a four-month-old labradoodle–English cream golden retriever mix—a gorgeous happy dog, she told us. The only problem was that Tonya had to crate him all day while she was at work, and this gorgeous happy dog had outgrown his crate.

We drove down from our new home in Boone, North Carolina, to Clemson, South Carolina, the next weekend and met Tonya and her dog, whose name, it turned out, was Buddy. He was a giant-pawed puppy, sloppy and beautiful with wiry hair that gave him the appearance of some British royal turned out of Buckingham Palace for wetting the rugs. He already weighed thirty pounds. He was already licking my children’s faces.

They fell in love.

We took him home.

End of story.

Or so we thought. We discovered, about three minutes after climbing into the car with him, he was an active dog. Make that an active puppy—a breed all its own. He climbed, licked, jumped. He was the sweetest, most loving thing ever. But he was in constant motion. Also, he chewed: That week he chewed up both my wife’s passport and her eyeglasses. He chewed pillows and toys and plastic taken from the recycling bin. He chewed our fingers and TV remote. He chewed the soft L.L. Bean dog bed we’d gotten him.

“I’m too old for a puppy,” my wife declared.

She was, in her defense, down on all fours squinting (without her glasses) and gathering the blue shards of her passport.

We decided a name change was in order. We’d already had a Buddy. We needed a clean start. We needed a name that signaled the regal dignity our new pup would grow into any day now. We needed a Basho. Yes! Basho, the Japanese Zen poet. An aspirational name indicating calm and focus.

Basho it was.

Only Basho (think stillness, think pu’er tea in the lotus position) quickly became Bash (as in his head against everything). Basho the poet might have achieved enlightenment, but Bash the dog was a wild man.

I was headed from my office to class the day my wife called.

“Guess who I just got off the phone with?” she asked. Then, before I could answer: “The dogcatcher!”

“The what?”

“The dogcatcher.”

“That’s still a thing?”

Apparently, it is. We live at the dead end of a long gravel road, but it seems Basho had decided to go exploring. At the end of our road, across the highway, across a field, across practically the Watauga freaking River, Basho had discovered a house with chickens and, in his big goofy way, decided to play with them.

“Oh, he’s just loving on them,” my wife told the animal control officer (they aren’t really called “dogcatchers” anymore). “He’s actually really gentle.”

“Well, gentle or not, he’s about to love ’em to death, ma’am.”

She drove over.

She and the animal control officer spent a half hour chasing Basho, who thought it was all a big game. Finally, they both managed to corral him.

He rolled onto his back to have his belly rubbed.

I like to think they laughed and cried.

I like to think they bonded.

A few days later we took him hiking for the first time. It was supposed to be an easy break-in: a walk along the gravel road that parallels the river. But as we were clipping the leash to his collar, Basho slipped beneath the gate of the car, dodged my wife, and galloped up the road. We gave chase on foot, and then gave up and gave chase in the car. Basho ran a half mile at twenty miles an hour—with a brief pause to surprise an old woman hanging out her wash—and

then flopped into the weeds for yet another belly rub. My wife and I were a bit exasperated, but my son was simply impressed.

“Dad, Basho just easily broke the world record for eight hundred meters.”

“But he is a quadruped,” I pointed out.

“And he doesn’t listen,” my wife added.

My son was unmoved.

He scratched Basho’s big blond tummy.

“You’re the sweetest and the fastest thing ever,” he told him.

Which was sort of true, but not very helpful.

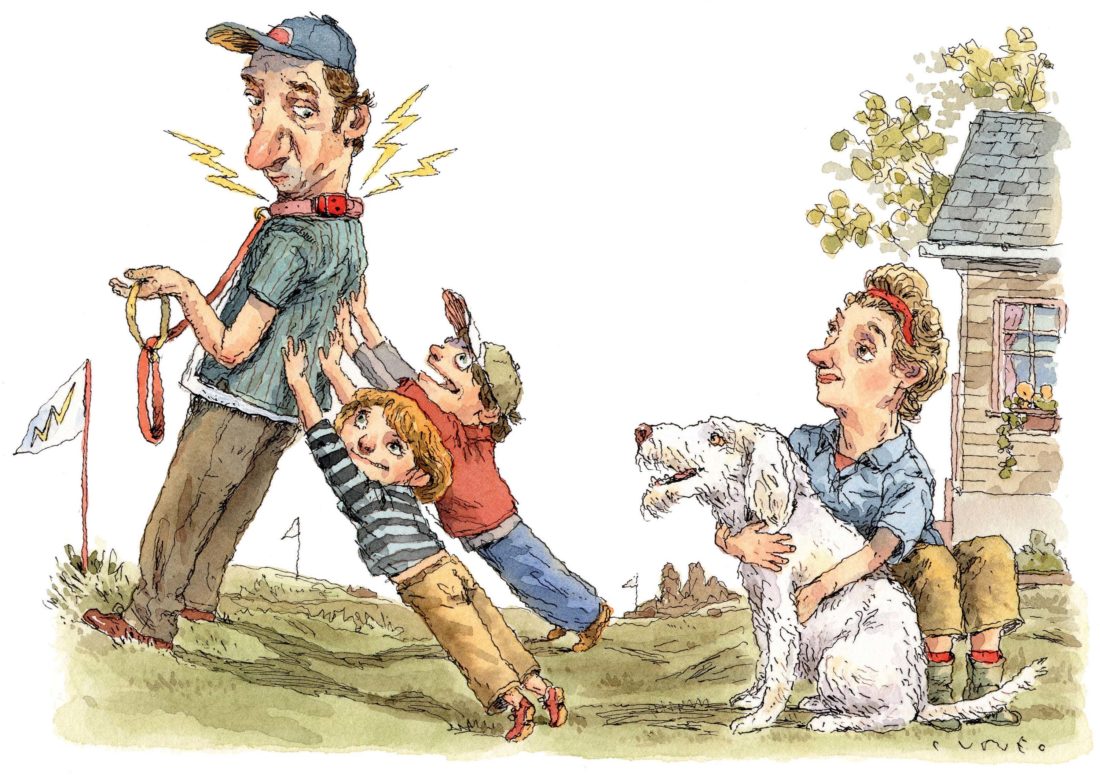

That week we decided to invest in an invisible fence. None of us were crazy about the decision, but we couldn’t face another encounter with the animal control officer. We got the sort of collar that emits a beeping sound as you approach the boundary before finally emitting a small shock. The children insisted I try it, so one Saturday morning I began walking apprehensively away from the house, the collar in my hand.

“It beeped,” I told the children.

“Keep going,” they told me back.

“It beeped again.” And it had, louder and faster, as if detecting it was in the grasp of some middle-aged idiot.

“But Dad,” my son said, “we need you to make sure it isn’t too strong.”

I wasn’t keen on this.

“But won’t Basho stop when he hears the beeping?” I asked. “This seems unnecessary.”

“It’s absolutely necessary,” my son said.

“Just touch the electrodes and walk already,” my daughter told me.

She said it with such seven-year-old authority that I did.

The collar beeped wildly. The shock was no more than a prickle. We declared it harmless. The children wrapped Basho in celebratory hugs.

“Now you’ll be safe with us forever,” my daughter said.

Basho flopped on his back, got his belly rubbed, then promptly went inside and ate his new bed.

“I’m too old for a puppy!” I heard from the living room. It was my wife, picking up the stuffing. I sympathized, even if I sometimes wondered who among us was young enough for one.

The answer, it turns out, was our children.

The answer, it turns out, was all of us.

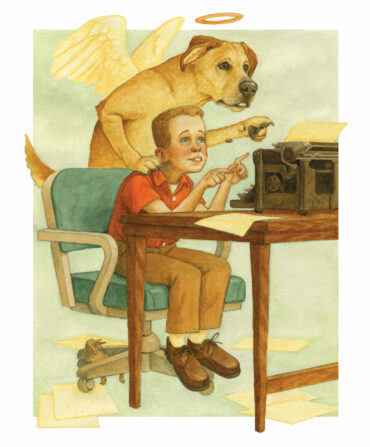

We should have seen it coming.

How inevitable it was. How watching our son and daughter fall in love with a big sweet sloppy dog, we would fall in love with that same big sweet sloppy dog. My wife and I both kept talking about the travails of a giant puppy, but now and then I’d catch her whispering sweetly into Basho’s floppy ear. Then one day, I discovered Basho channeling Darrell Hammond channeling Bill Clinton, circa 1999 (we’re not the only ones who give our dog a voice, right?). I discovered myself scratching his belly and asking all the things you ask of beloved dogs.

He was a good boy, yes, did he know how good a boy he was?

Basho, sprawled on his back, started telling me about Little Rock.

Did he know how sweet he was?

Apparently, since he was swishing his tail and talking about Chelsea and the Oslo Accords.

I was scratching and rubbing and talking so intently I barely noticed how still he was, or happy I was. The thing I did notice, the thing I felt, the thing I sensed between this goofy dog and this doting man, it wasn’t calm or focus or any of the other things I’d hoped for.

It was something so much better.

Let’s call it love.

Mark Powell is the author of six novels, most recently Firebird, and directs the creative writing program at Appalachian State University.