This week, the town of Surry, Virginia, lost a titan and country ham lost one of its greatest champions when Samuel Wallace Edwards, Jr. passed away. “We lost a half-century of expertise, a half-century of leadership, and a guiding food world light,” says John T. Edge, director of the Southern Foodways Alliance.

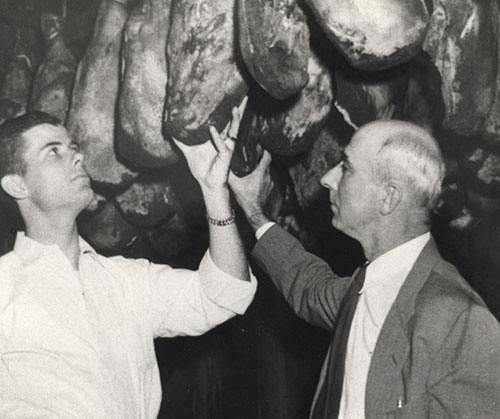

Edwards, Jr., who went by “Wallace,” with his father.

The men of the Edwards family have spent nearly a century in the ham business, curing country hams the old-fashioned way. “Without a doubt, they have one of the finest reputations in the country ham business,” Tennessee ham producer Allan Benton says. Edwards, Jr. was the son of the company’s founder, who was working as a captain on the ferry between Surry and Jamestown when he began selling sandwiches stuffed with his family’s country ham. The sandwiches were popular enough that the senior Edwards began selling country ham for a living, bringing his son into the fold at a young age.

By the time that Edwards, Jr. took over the business, many of his peers were abandoning the old ways in favor of faster, more cost-effective methods of curing hams. Edwards refused to yield. “He epitomized what being a Virginia gentleman was about. He was dedicated to his family, number one, and then to the heritage of Southern food and the community at large,” says Keith Roberts, who got to know Edwards, Jr. and his son, Samuel Wallace Edwards III, after joining the company several years ago. “In an age when people were choosing to go after a quick buck, he stayed true—to the recipe, the methods, the history, everything.”

With his commitment to tradition, Edwards, Jr. set the stage for his son to bring the family’s ham to the national stage in the twenty-first century. Today, it can be found in some of the country’s most prestigious restaurants, including New York’s Momofuku and Charleston, South Carolina’s Husk. “In addition to being my father and mentor, he was also my best friend,” Edwards III says. “I will miss having him as a sounding board for life and business decisions.” And thanks to the values that Edwards, Jr. passed on to the next generation, an age-old family tradition shows no sign of flagging.