In the middle to late 1800s, Lincoln, Grant, and Twain began removing fat from American prose. It’s interesting to compare their lean written sentences with the bloated ones of their contemporaries.

Along came Ernest Hemingway in the 1920s and finished the job. His cleanly written deep stories stunned some young readers into wanting to become writers. I chanced upon A Farewell to Arms when I was nineteen and finished the last page hungry to teach and write fiction. Hemingway’s descriptions of objects and movements of people and animals were, to me, often more than dead-on—some sentences and paragraphs seemed to me not so much understood as felt.

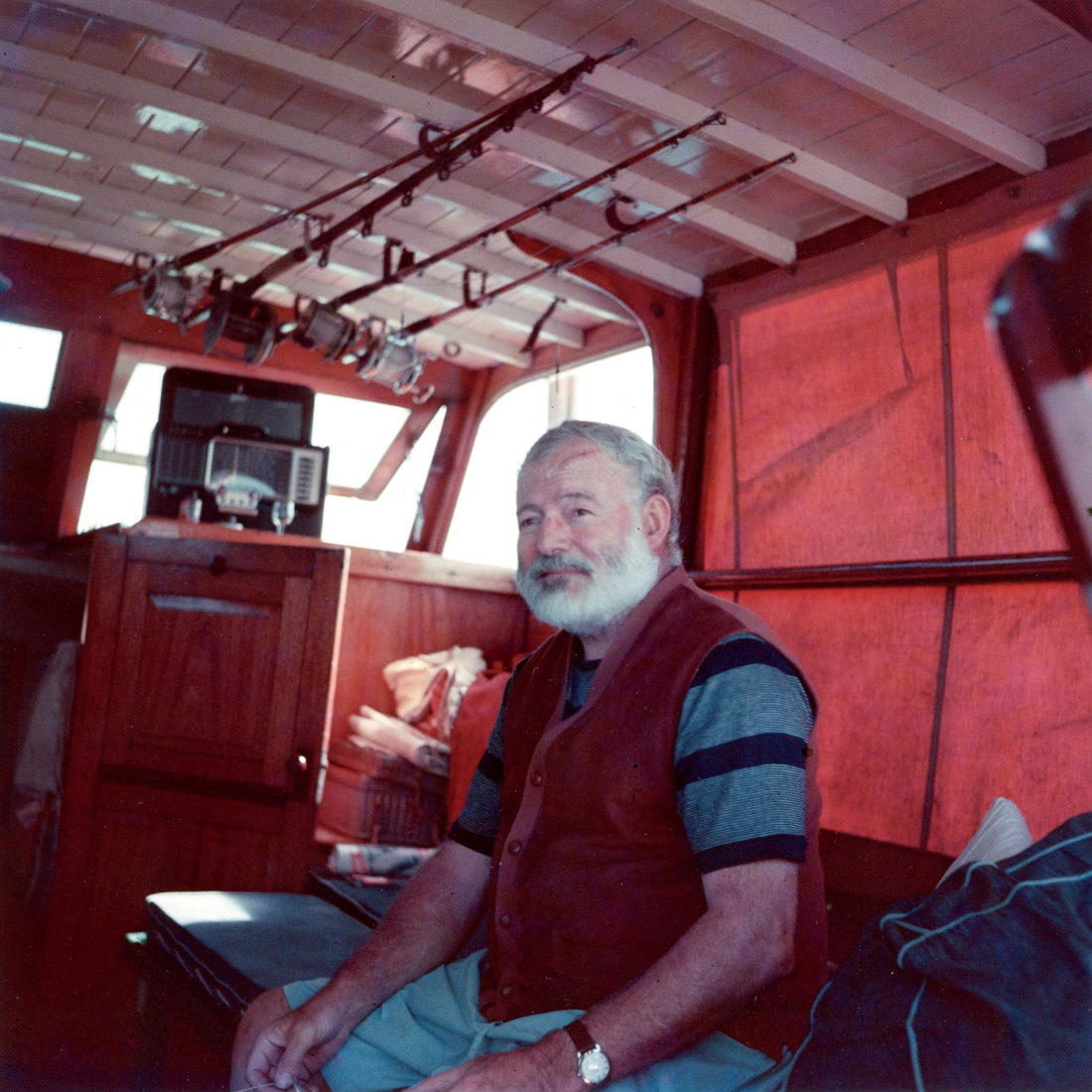

Hemingway’s Boat (Knopf), by Paul Hendrickson, coming on the fiftieth anniversary of the writer’s infamous death in 1961, is not a biography. Rather, Hendrickson’s complex but clear and easy-to-follow narrative revolves around one of Hemingway’s loves, his fishing boat, Pilar. Hemingway bought the sturdy vessel in 1934 at the height of his artistic powers. He was thirty-four. For the rest of his life he often fished from it, ate on it, and slept on it, near his homes in Key West and then Cuba.

By focusing on Hemingway’s relationship to his boat—and to the people who spent time on it (wives, sons, friends, lovers, mates, writers, publishers, etc.)—Hendrickson throws fresh light on his passions, faults, loves, art, and inner life. He gives us several previously untold “shadow stories,” mini-biographies of two of Hemingway’s friends and his son Gregory.

On the surface, Hendrickson reaches readers interested in boats and/or fishing. In these pages you walk the length of this unique thirty-eight-footer; examine its engines, galley, and lowered stern wall (and other modifications). You sit in the fighting chair and feel the pull and jumps of several giant marlin.

Hendrickson digs deeper. Hemingway’s mix of faults and gifts—which Hendrickson has chronicled fairly—led one of Hemingway’s friends, Archibald MacLeish (as quoted by Hendrickson), to say: “It would be so abundantly easy to describe Ernest…as a completely insufferable human being. Actually, he was one of the most profoundly human and spiritually powerful creatures I have ever known.”

For the Hemingway aficionado—the Hemingway scholar even—this book is big because it delivers convincing and somewhat new information about Hemingway’s confused love for his children and the emotional tumult left in his wake. Deep in his narrative Hendrickson bravely raises an issue that our culture in general is not ready for. He asks: “How did we, meaning the world, read Hemingway’s work so wrong, for so long? How did we read the man himself so wrong, for so long? Well, he misdirected us with the mask. The mask wasn’t false, a lie, a fraud, as so many detractors have wished to say. The hypermasculinity and outdoor athleticism were one large and authentic slice of him. But beneath the mask was all the rest, which is why his work endures, why his best work will always have its tuning-fork ‘tremulousness,’ as it’s been called.”

“The rest” in “beneath the mask was all the rest” refers to apparent transgendered sexual tendencies expressed in Hemingway’s fiction—especially in work published after the writer died.

Hendrickson’s in-depth analysis of those tendencies, and also of Hemingway’s relationship to his trans-

sexual son, Gregory (who died tragically in a jail cell), offers insight into Hemingway the artist and Hemingway the man. The book’s ending takes us some distance from Hemingway’s boat, but I forgive Hendrickson this detour. This book, with fresh information and insights, adds significantly—as many other books have not—to what we know about a complicated and great American writer.