Few cities have flora as emblematic as the live oaks that tower over Savannah’s squares, so intertwined with the identity of the town that it’s hard to imagine Savannah without them. But many of the city’s live oaks will die around 2040.

The lifespan of a typical live oak can be upwards of five hundred years (or even more), while Savannah’s are only a little over one hundred. But these aren’t typical live oaks; they’re part of an urban canopy. “[The oaks] were not meant to live in urban environments,” says Zoe Rinker, executive director of the Savannah Tree Foundation. “They’re starting to see the wear and tear.” The oaks’ roots are compacted by streets, their leaves absorb pollution from traffic, and the trees are dealing with stress from intensifying heat from climate change, she says.

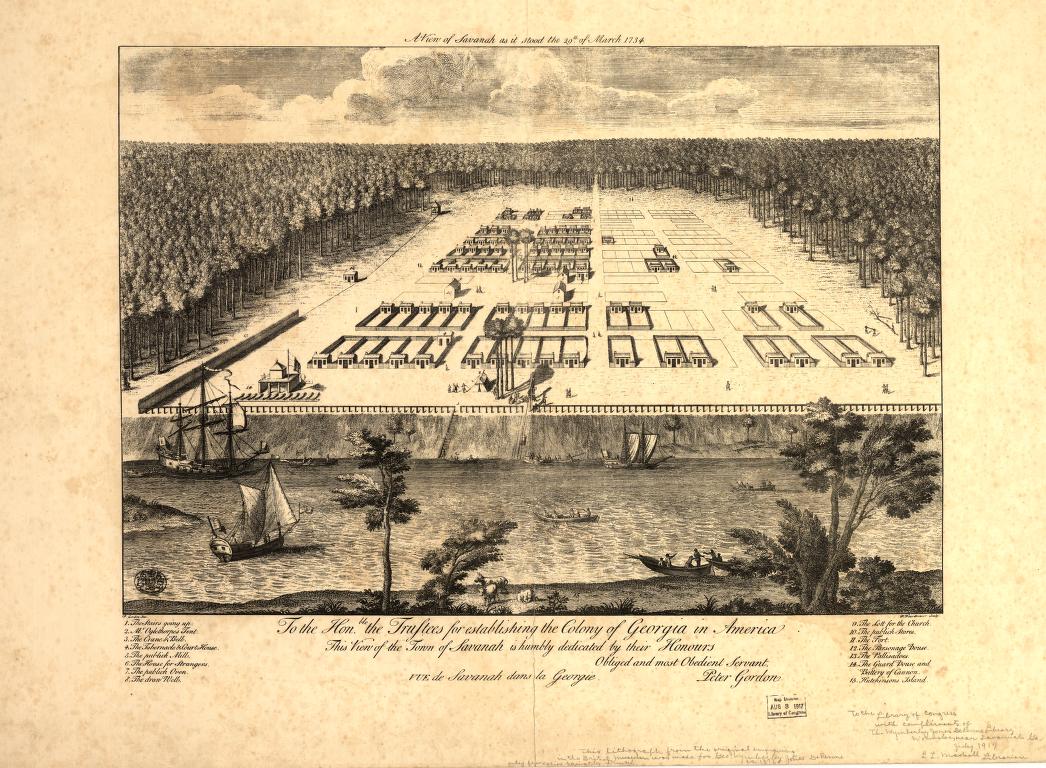

When the city was founded in 1733, Savannah’s canopy looked tremendously different. Longleaf pines prevailed until the settlement was clear-cut. But a city with no shade isn’t a great place to live, so Savannahians began planting fast-growing trees like chinaberries and sycamores. Most of these were destroyed when a Category 3 hurricane decimated the forest in 1893, and the city replaced them with strong, squat, storm-resistant live oaks around 120 years ago.

When the oaks were originally planted, dirt roads and carriages reigned; no one was worrying about pavement and cars. But oaks are kind of like leafy icebergs: They have brilliant canopies above ground, and nearly as much biomass exists underground, Rinker says. “If you’re compacting that with daily traffic, or with asphalt or with concrete, it’s making the tree work twice as hard to survive,” she says.

The city is already working to replace its 15,000 or so live oaks, gradually planting new saplings as the old ones fall on public land, says Scott DeArmey, assistant director of Savannah’s park and tree department. That means the city’s lush, moss-draped aesthetic won’t be lost in the long term, though the short term will see smaller, younger oak specimens around town. “Within fifteen years you’ve got a tree that you can stand under with shade. And probably within forty years, you’ve got what you would consider a mature oak tree,” he says.

The Savannah Tree Foundation is also tackling tree loss on privately owned land, including at Wormsloe State Historic Site’s iconic avenue of oaks. And Rinker hopes to use a million-dollar grant to address inequality by planting native trees, including oaks, in areas of Chatham County that have flooding issues and little tree cover, with the aim to diversify the canopy with other species. “Live oaks are always going to be a part of Savannah’s urban forest,” Rinker says. “It’s part of what makes us who we are. But I do think you’re going to not see quite the monoculture of live oaks moving forward.”

New Life for Dead Trees

When Darcy Melton was nine years old, her greatest delight was climbing the strong, sprawling limbs of a live oak tree near her grandparents’ house. For fifteen glorious minutes a day after school, Melton and her friends were allowed to run through the sunshine filtering through the Spanish moss of Savannah’s McCauley Park oak.

When the McCauley oak came down last year at around 120 years old, the city called Re:Purpose Savannah, a company that reclaims materials from historic buildings, and asked them to find a use for the oak. The team milled the branches and trunk several times, kiln-dried the slabs, and announced that the wood was available for purchase. “Folks showed up in droves,” says Kelley Lowe, the director of salvage at Re:Purpose. Melton was one of them.

Melton and her husband (who used to play with her under the tree as a kid) turned an oak slab into an artist’s palette. In her studio, underneath dollops of oil paint, the oak’s grain shines through. “There’s something that, for me, is unexplainable about using the palette, like it definitely imbues something on my art and something on my soul,” Melton says.

Lumber from the oaks also has practical appeal for furniture; live oak wood is so dense and strong that the U.S. Navy used it for building warships. In the coming years, Re:Purpose has plans to craft benches out of the McCauley oak to bring part of the beloved tree back to the park. “It’s the most challenging and the most rewarding wood species I’ve ever worked with,” Lowe says. “Because of the way that live oaks twist and turn, the figure in the grain is incredible…There’s a lot of character and beauty.”

The dying oaks will also achieve another degree of immortality: The Savannah Tree Foundation plans to grow saplings from their seeds inside their nursery. Those legacy saplings will then be planted around the county, where they will grow into the quintessential titans of Savannah in mere decades. Says Rinker, “We may be losing these trees now, but we’re planting the next generation that can create an even more beautiful Savannah.”