DRINK

Georgia

Mad for Madeira

In 1825, when the Revolutionary War hero General Lafayette visited Savannah, the local newspaper recorded fifty-one arm-wearying toasts to him over glasses of Madeira. The brandy-fortified wine, which crossed the Atlantic from the eponymous Portuguese island, had been the city’s drink of choice since its founding, in 1733. “The Ann, the first ship to bring English settlers to Georgia, stopped in Madeira and loaded up with wine from the island,” says Jamie Credle, director of Savannah’s Davenport House Museum. Along with her husband, the writer Raleigh Marcell, Credle is resurrecting the Madeira toasting tradition at the circa-1820 Davenport House. Every Friday and Saturday night in February, visitors can reserve a spot to experience Potable Gold: Savannah’s Madeira Tradition, an immersion into the city’s—and the drink’s—history. After exploring the historic house by candlelight, seeing the fanciful hand-stamped wallpapers and stately Federal furniture, guests encircle a table to pass around a decanter of Rainwater, a dry Madeira long favored here, and make toasts. Credle and Marcell then move the party up the massive staircase to a long-unfinished garret laden with candles to taste Malmsey, a darker, sweeter variation. From there, imbibers can soak in the dazzling nighttime views of the river and city where the wine first touched Southern ground. “The British sent whole shiploads of grapevines over from Madeira in the eighteenth century in hopes of turning Georgia into a wine-producing colony,” John Berendt wrote in Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, his bestselling 1994 portrait of the city. “Well, the vines died, but Savannah never lost its taste for Madeira.” If the folks at the Davenport House have anything to do with it, Savannah never will. davenporthousemuseum.org

ARTS

Alabama

BEAD BY BEAD

As the birthplace of Mardi Gras in the United States, Mobile has Carnival traditions and history that go together like beans and rice. (Sorry, New Orleans—Mobilians were celebrating the festival fifteen years before your city was even founded in 1718.) Throughout those centuries, few have done more to promote the festivities than John Augustus Walker, who was born in the Alabama port city in 1901 and became an artist and designer for the Infant Mystics, one of Mobile’s oldest parading societies. More than a hundred of Walker’s oil paintings, sketches, and watercolors appear in the Mobile Carnival Museum’s exhibition John Augustus Walker: Artist-Designer of Mobile and Carnival (through March 9). “Walker’s artistry tells not only the story of Mardi Gras during the early twentieth century, but of the first generation of professionally trained Southern artists,” says curator Cartledge Blackwell. Walker studied at the St. Louis School of Fine Arts and became a heralded Works Progress Administration muralist during the Great Depression. But his float designs—elaborate moving sculptures such as giant popping champagne bottles and wildly colorful butterfly wings bursting from spools of yarn—helped lay the foundation for the way Mobilians celebrate today. Proof: In a concurrent exhibit, the museum showcases mementos from all seventy-three still-thriving mystic societies, such as the Order of Myths (founded in 1867) and the Maids of Mirth, one of Mobile’s first women’s societies. mobilecarnivalmuseum.com

GARDEN

Arkansas

Spring

Each February and March, 150,000 sunny daffodils trumpet spring at the University of Arkansas’s Garvan Woodland Gardens in Hot Springs, blanketing the onetime private retreat of its namesake, Verna Cook Garvan, in bright white, butter-yellow, and flame-orange layered ruffles. For forty years, the amateur gardener planted and tended nearly three hundred varieties of daffodils, now complemented by swaths of tulips, hyacinths, azaleas, dogwoods, and forsythias, before bequeathing the land to the university. To honor Garvan’s decades of cultivation, crews spent the last few months adding hundreds of bulbs and thinning surrounding trees at the most notable spot, dubbed Daffodil Hill. For home gardeners looking to refresh their own heritage plantings, Janet Carson, an Arkansas Extension horticulture specialist who works with the gardens, advises a long view: “Right when the bud emerges, add some fertilizer. That gives them nutrition they need for the next year.” And to make a statement every spring, she says, plant generously. “Don’t put just ten bulbs in the ground. Go big.” garvangardens.org

ANNIVERSARY

Florida

AIRSTREAM DREAM

Since the dawn of the automobile age, snowbirds have flocked to the Sunshine State. Few have done so with more bravado than the Tin Can Tourists, an auto-tourism group formed in 1919. The name predates the sleek metal midcentury campers associated with the group now; instead, it harks back to the Ford Model T, nicknamed “Tin Lizzie,” which carried tents and pulled early trailers. The first members attached tin cans to their cars’ radiator caps, showing everyone on the road they belonged to the club. Throughout the twentieth century, TCTs escaped the icy North and assembled in spots around Florida. “From World War II on, the numbers diminished, which happens to a lot of organizations if you don’t appeal to the next generation,” says Forrest Bone, an old-school campground fan who revived the Tin Can Tourists in 1998 and is now director of the club. The group numbers some 2,300 members who circle up their wagons—shiny silver 1950s Airstreams, canned-ham campers from the 1960s, and 1970s ruby-red caboose trailers—a few times a year, although ownership of such mobile memorabilia isn’t required. Aficionados will congregate at the Centennial Celebration (February 19–24) in Brooksville (fifty miles north of Tampa) for excursions by retro ride, lectures on the history of the club, a limited-edition Buffalo Trace bourbon tasting, and a Saturday open house when guests can walk among the plastic flamingos, string lights, striped awnings, and aluminum picnic tables to experience the vintage trailers in their historic habitat. tincantourists.com

Tim Bower

STYLE

Kentucky

SQUARE ROOTS

Coco Chanel turns heads with her iconic little black dress sewn in faux leather, Rosie the Riveter sports her instantly recognizable red polka-dot head scarf, and a ribbon-rendered bloom is stitched in place in Aretha Franklin’s hair. The colors, textures, and styles of the 107 quilts in the HERstory exhibit at the National Quilt Museum in Paducah (through April 9) are a patchwork achievement by fiber artists from seven countries who celebrate groundbreaking women, honoring them in fabric. “Some feature portrait likenesses of famous females as the focus,” says Susanne M. Jones, a quilter from Potomac Falls, Virginia, who curated the exhibit. “Others spotlight the woman in a more symbolic way or tell a story.” Jones’s own quilt includes black-and-white images of the four girls killed in the 1963 Birmingham church bombing, printed on filmy organza that fills an outline of Alabama. In the center of her creation, Jones thread-sketched a portrait of her mother-in-law, Marna Williams, surrounded by raw-edged appliqué vignettes of Williams’s civil rights work in 1960s Birmingham. “She’s not well known,” Jones says. “But she was my hero.” quiltmuseum.org

FOOD

Louisiana

MUDBUG CRAWL

Michael Blanchard can’t remember the first time he ate crawfish. “You feed kids crawfish when they start eating,” says the Houma, Louisiana, restaurant owner. Along the Bayou Bounty Trail, the Gulf-hugging route from Lafayette to Port Fourchon, January to early July is the time for harvesting the crustaceans and serving them in heaping boils full of sausage, corn, potatoes, and onions—and the season usually peaks in March and April, serendipitously during Lent. “We’re predominantly Catholic around here, and because we’re not supposed to eat meat, most Cajuns eat seafood,” Blanchard says. “But it’s by no means a sacrifice.” Rather, it’s a livelihood. Blanchard and his wife, Debra, have served crawfish for twenty years at Boudreau & Thibodeau’s Cajun Cookin’ in Houma. Theirs is one of dozens of spots along the trail (also check out Prejean’s in Lafayette and Landry’s Seafood and Steakhouse off US-90 in Jeanerette) where locals and visitors alike can pinch the tails and suck the heads, as they say. What they don’t say: crayfish. Blanchard explains, “That’s what tourists call them.” louisianatravel.com

Tim Bower

CONSERVATION

Maryland

SEAL OF APPROVAL

The veterinarians at the new Animal Care & Rescue Center, part of Baltimore’s National Aquarium, have already seen a zebra shark with a bacterial infection, a stingray that was due for a mouth-to-tail physical, and a pufferfish in need of a new diet plan. At capacity, 5,000 animals (from aquarium exhibits or the wild) can be treated in the nearly 60,000-square-foot facility, which doubled the aquarium’s medical space. Guests can see the healing work themselves during newly introduced guided tours. “Through main hallways, visitors can look into rooms and go into several areas that don’t have an active quarantine in them,” says curator Ashleigh Clews. Although the center primarily treats any of the 20,000 fish, mammals, and reptiles in the aquarium, its goal for wild animals is a healthy return home. One such patient was Marmalade, a harbor seal who, during his winter migration around Ocean City and Assateague Island in 2018, stopped on the Maryland coastline, struggling with pneumonia and an infection called seal pox. His treatment included a stay in the center’s new seal suite, one of the stops on the tour. After two months, workers discharged a healthy Marmalade, with a splash, back into his native waters. aqua.org

MUSIC

Mississippi

TRUE BLUES

The tin-roofed clapboard building, called the 100 Men D.B.A. Hall, looks unassuming standing along a back road in Bay St. Louis. But step through its blue doors and onto its wood floor, and you can sense the energy of nearly a century of music. “When you’re standing in the hall and you know that Etta James was on that stage, and Ray Charles and James Brown, you have this tingling sense of something otherworldly,” says Rachel Dangermond, a local who recently purchased the fading venue and plans to revive it and book music and art shows there. Built in 1922 to host meetings for the Hundred Members Debating Benevolent Association, an African American social group, the hall became a popular stop on the “Chitlin Circuit,” a 1950s network of black music clubs. Dangermond hopes to retain most of the original features, and commissioned muralists to add an exterior storyboard illustrating the venue’s history. On March 10, watch the artists at work and stay for an appearance by the Mad Potter of Bay St. Louis, who shapes clay into bowls with his bald head, plus a concert by the New Orleans band Gal Holiday and the Honky Tonk Revue. “The hall upholds the sacred act of presenting live music, which is the heart of Mississippi,” Dangermond says. “Musicians feel it, visitors feel it. The hall is more than post and beam—it’s memory and music.” the100menhall.com

STYLE

North Carolina

PARTY LIKE A VANDERBILT

For Gilded Age gatherings, like those at her brother George Vanderbilt’s sprawling estate tucked among the mountains surrounding Asheville, the heiress Florence Vanderbilt Twombly wore a peach silk gown sprinkled with beaded butterflies. In the Biltmore Estate’s new mansion-encompassing exhibition, A Vanderbilt House Party (February 8–May 27), curators led by the Oscar-winning costume designer John Bright (you’ve seen his work on Downton Abbey) remade the ensemble. “We worked with embroiderers in London who hand sequined the dress and used different colors of metallic threads to make the butterflies,” says curator Leslie Klingner. “Not only is it a stunner, it’s hard to believe it’s not original.” More than fifty additional garments—including re-creations of George Vanderbilt’s sporting tweeds and Edith Vanderbilt’s casually elegant polka-dot bodice and silver-belted skirt—will grace vignettes of entertaining. On the new audio tour (included in the price of a ticket if you book online), voice actors re-create a turn-of-the-century gala from start to finish, beginning with the breakfast room and moving to all four levels of the home, which will be drenched in floral arrangements gathered primarily from the estate’s gardens. Pause in the Banquet Hall, where for one of the first times in public, real Vanderbilt family silver, Baccarat crystal, and Spode china will be set for a multicourse dinner. “Everything they did here,” Klingner says, “was the ultimate in gracious Southern hospitality.” biltmore.com

HISTORY

South Carolina

LOWCOUNTRY LEGACIES

When the Union army reached South Carolina’s Sea Islands in late 1861, they found almost 10,000 abandoned enslaved persons. With their status hovering somewhere between property and contraband of war, these Central and West African descendants, also known as the Gullah Geechee people, wrote the opening chapters of Reconstruction in places like Mitchelville, the first self-governed town of freedmen in the United States, located on Hilton Head Island. Today Hilton Head honors the story of these individuals and their culture, which still pulses throughout the Lowcountry, with February’s monthlong Gullah Celebration. Local guides lead tours of what remains of Mitchelville, which last year was dedicated as the Mitchelville Freedom Park, and share details of ongoing plans to excavate and restore parts of the site. On February 2 at the Historic Cherry Hill School, visitors can watch (and eat) as cooks prepare a traditional coastal breakfast of stewed oysters, shrimp in gravy, fried fish, and grits. A five-part music series at area churches concludes with an evening of gospel and Gullah songs at Central Oak Grove Baptist Church on February 28, and the Arts Center of Coastal Carolina hosts a monthlong exhibition featuring the creations of contemporary Gullah artists. The entire event, says director Courtney Young, centers around one purpose: “It’s a reminder of the resilience and brilliance of people who thrived under oppression and still made it.” gullahcelebration.com

ANTIQUES

Tennessee

GOING FOR A SONG

“I’m a classicist, and there’s nothing I love more than antiques,” says Carolyne Roehm, the author and former fashion designer who has homes in New York, Connecticut, Colorado, and South Carolina. At the Antiques and Garden Show of Nashville (February 1–3), she’ll speak alongside such Southern personalities as Grammy-winning country star Faith Hill, architect Bobby McAlpine, and interior designer Ray Booth. Music City’s show is the longest-running and largest event of its kind, drawing 15,000 attendees and top dealers and garden designers from the South and beyond. The event theme, “A Passion for Home,” connects to Roehm’s latest book, Design & Style: A Constant Thread, which examines the string of creativity in her career and pastimes of decorating and gardening. She’ll find plenty of antiques among the more than 150 vendors, who offer art, furniture, and botanicals, from nineteenth-century barometers to rare bromeliads. It would be difficult for serious collectors like Roehm to leave empty-handed. “I always tell myself, ‘No, Carolyne, you need nothing,’” Roehm says. “But with this show, I’m sure there will be something I decide I need once I get there.” antiquesandgardenshow.com

ARTS

Texas

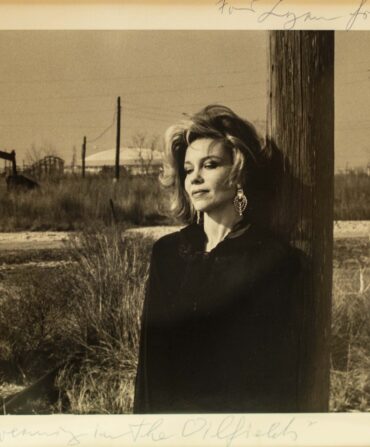

THE OTHER O’KEEFFE

What led Georgia O’Keeffe to demand that her also-talented younger sister Ida not exhibit her work? Was it artistic jealousy? A love triangle gone awry? Plain old sibling rivalry? After four and a half years of research on the lesser-known O’Keeffe—and her oil paintings, watercolors, and drawings—Sue Canterbury, a curator at the Dallas Museum of Art, thinks it could have been a bit of all of the above. Canterbury has uncovered more than forty works for Ida O’Keeffe: Escaping Georgia’s Shadow (through February 24) that prove Ida was an exceptional artist in her own right. “The sisters were generally close growing up,” Canterbury says. But as Georgia became famous for her large-scale floral paintings, Ida also started to slowly make her way in the Depression-era art industry with teaching gigs. Georgia wasn’t having it. That could have had something to do with the infatuation that Georgia’s husband, the photographer Alfred Stieglitz, had for his wife’s sister. “In the fall of 1924, Ida stayed with them on Lake George in New York, and he was highly flirtatious with her,” Canterbury says. (There’s no evidence that Ida acted on Stieglitz’s advances.) Although Ida never gained international prominence for her art, her pieces are part of private collections across the country. She completed one of the most evocative paintings included in this exhibition in 1938, while teaching in San Antonio. Titled Star Gazing in Texas, it features a frame covered in silver stars, and at the center, bathed in moonlight, a woman soaking up the shine on her own. dma.org

LITERATURE

Virginia

WORD ASSOCIATION

There are book festivals, and then there’s the Virginia Festival of the Book. The literary bonanza (March 20–24) brings as many as 30,000 bibliophiles to Charlottes-

ville for 250 book discussions, most of them free to attend. There are events for readers with all kinds of interests—former investigator turned crime writer Don Winslow will share the inspiration behind his latest novel, The Border, and Nickel and Dimed author Barbara Ehrenreich will speak about her new book on aging with a sense of humor, as well as her reporting experiences, which include a stint as a waitress in Key West. One of the strongest themes emerging among this year’s powerhouse lineup of speakers is the importance of literature for young readers. Jason Reynolds, a D.C.-area native, a poet, and a Walter Dean Myers Award winner for Outstanding Children’s Literature, will discuss his coming-of-age writing, and Jarrett J. Krosoczka, a children’s author whose new autobiography, Hey, Kiddo, was a 2018 National Book Award finalist, will give a reading on March 20 at New Dominion Book Shop. In sharing the harrowing reality of his own youth, his mother’s opioid overdose, and the freedom he’s found in writing, Krosoczka says, “I hope young people can experience and learn about these difficult truths for the first time on the page and not in real life.” vabook.org

ARTS

Washington, D.C.

LIGHT AND SHADOW

In 1802 in Philadelphia, a freedman named Moses Williams went to work for the artist Charles Willson Peale, who taught him how to use a silhouette-making machine called a physiognotrace. Working at Peale’s Museum, Williams became a sought-after silhouette artist known for his extraordinary precision in portraiture. But Williams never got any credit, his pieces were stamped “Museum” instead of with his name—and the master of light and dark remained in the shadows, until today. In the National Portrait Gallery’s exhibition Black Out: Silhouettes Then and Now (through March 17), Williams’s work is on display, properly credited to him, along with the creations of modern silhouette greats Kara Walker (don’t miss her life-size and provocative depictions of antebellum plantation life) and Kumi Yamashita, a Japanese American artist who uses light beams to sculpt shadows against white walls. Yamashita’s artwork explores how the tension between positive and negative space has made silhouette portraiture a centuries-old tradition. “When we confront the void with just enough outline and just enough light to make out something,” she says, “we activate every ounce of our imagination.” npg.si.edu

Tim Bower

ANNIVERSARY

West Virginia

COME TOGETHER

“The passage of the Potomac through the Blue Ridge is perhaps one of the most stupendous scenes in Nature,” Thomas Jefferson wrote in 1783 as he gazed from what is now called Harpers Ferry, with views of West Virginia, Virginia, and Maryland. Jefferson didn’t know that amid all that beauty, Harpers Ferry would become a historical hotbed, home to John Brown’s abolitionist raid in 1859 and a major setting in the Civil War and the Industrial Revolution. “If the geology and geography weren’t here,” says Cathy Baldau, executive director of the Harpers Ferry Park Association, “the rest of the history wouldn’t have followed.” That convergence of nature and memory led President Franklin D. Roosevelt to declare the spot a National Monument in 1944. This year marks Harpers Ferry’s 75th anniversary of that distinction. The celebration kicks off in February with a yearlong speaker series. All the events, including walking tours, panels, book signings, and hikes, lead up to a weekend-long birthday party in June. No matter when you visit, make time to chart a path among the park’s twenty miles of trails, and stop at Jefferson Rock to see the same spot that inspired him: where the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers become one. nps.gov/hafe