Steve Keene doesn’t have your typical artist’s studio—in fact, he calls his creative space in New York City a “cage.” Tall chain-link fences act as one giant, communal easel for up to fifty plywood canvases fastened with wire. His paint-splattered floors testify to his roving from one end of the space to the other, brush in hand, for eight hours a day, nearly every day. “It looks like I’m trapped,” Keene says, “but, really, I’m protected in my fortress.”

Keene’s massive oeuvre of more than 300,000 pieces dates back twenty-five years to a strike of creative inspiration he had while volunteering as a DJ for a University of Virginia nighttime radio station. In Charlottesville, before Keene’s life became engulfed by painting, it was engulfed by music: “I was inspired by how musicians worked: how they performed and how small bands promoted themselves with boxes of cassettes, CDs, and fanzines,” he says. “All of that got me excited about creating something and getting it out in the world for people to share. Those homemade ways of getting your name out were so interesting to me—I liked doing everything ‘incorrectly.’” Keene, who had studied printmaking at Yale, began painting in between his jobs as a dishwasher, making strokes quickly and methodically to churn out fifty pieces a day. For the artist, studying printmaking fed right into his new practice. “There are so many starts and finishes, dos and don’ts. Even though I applied my printmaking principles, I was able to create my own discipline of painting.”

In the early nineties, Keene plastered his work on the walls of Monsoon Cafe, a Charlottesville Thai restaurant where he washed dishes, and local customers snatched them up to hang in their own spaces. The restaurant—and soon, the entire college town—became an ever-shifting gallery of Keene’s paintings. In 2017, the University of Virginia even included Keene’s paintings in an exhibit and book describing the history of the two-hundred-year-old school in a hundred objects. After all, they had saturated the community: Potential buyers, whether they were young college students or seasoned collectors, had a hard time resisting the artist’s affordable five-dollar price tag. But the money never mattered much to Keene, who just wanted to make enough to buy paint for the next series.

When Keene moved to New York City in the mid-nineties, that included a return to the world of music. As a DJ, Keene played tunes from the collection of ten thousand albums that surrounded him at the Charlottesville WTJU station. As his creative work took off, he was the one making those records. Musicians such as the Apples in Stereo, the Klezmatics, Silver Jews, Pavement, and the Dave Matthews Band collaborated with the artist for expressive, vibrant paintings for albums and posters, pushing his already hyper-accessible art to even more people. For a few bucks, indie-rock fans across the country could have a band’s new release and a Steve Keene painting in their home.

For the painter, sharing his work with a wide community was as much of a part of his creative process as lifting a brush. “Once, someone told me that their parents had one of my paintings in their bedroom ever since they were born,” Keene says. “And that was my intention. Growing up in Virginia, my own parents had all these weird historical, collectible things. I wanted my art to be like an American collectible.”

The newly released Steve Keene Art Book acts as the first-ever archive of Keene’s work. Produced by the photographer Daniel Efram, the record-sized monograph highlights more than three hundred pieces sent in from the private collections of fans, and includes essays by the Charleston, South Carolina–born street artist Shepard Fairey, the Virginian-born painter Ryan McGinness, and more. “Keene’s paintings aren’t precious commodities,” Efram says, “but they’re freely traded trinkets, passed around with lots of love.”

Here, Keene shares more about his creative approach, Virginia roots, and artistic Southern influences.

The South has a history of art as a community-binding, collaborative process. How do you see your work fit into this tradition?

I’m into folk art, and I really like Howard Finster from Athens, Georgia. He was an artist and a minister. In the last twenty years of his life, he saw a vision. He said he had to paint Bible quotes, things like that, and he became very prolific. He did an album cover for the Talking Heads, and R.E.M. even filmed a video in his garden. Sam Mockbee is another one I admire. He taught architecture classes at Auburn. Using recycled materials, he built structures for impoverished communities.

I started out selling my art cheap; there’s something fun about public events where people can just show up. It becomes like a record sale or yard sale. People who don’t have money can have my work. It’s like trading cards, something that people can pass on to others.

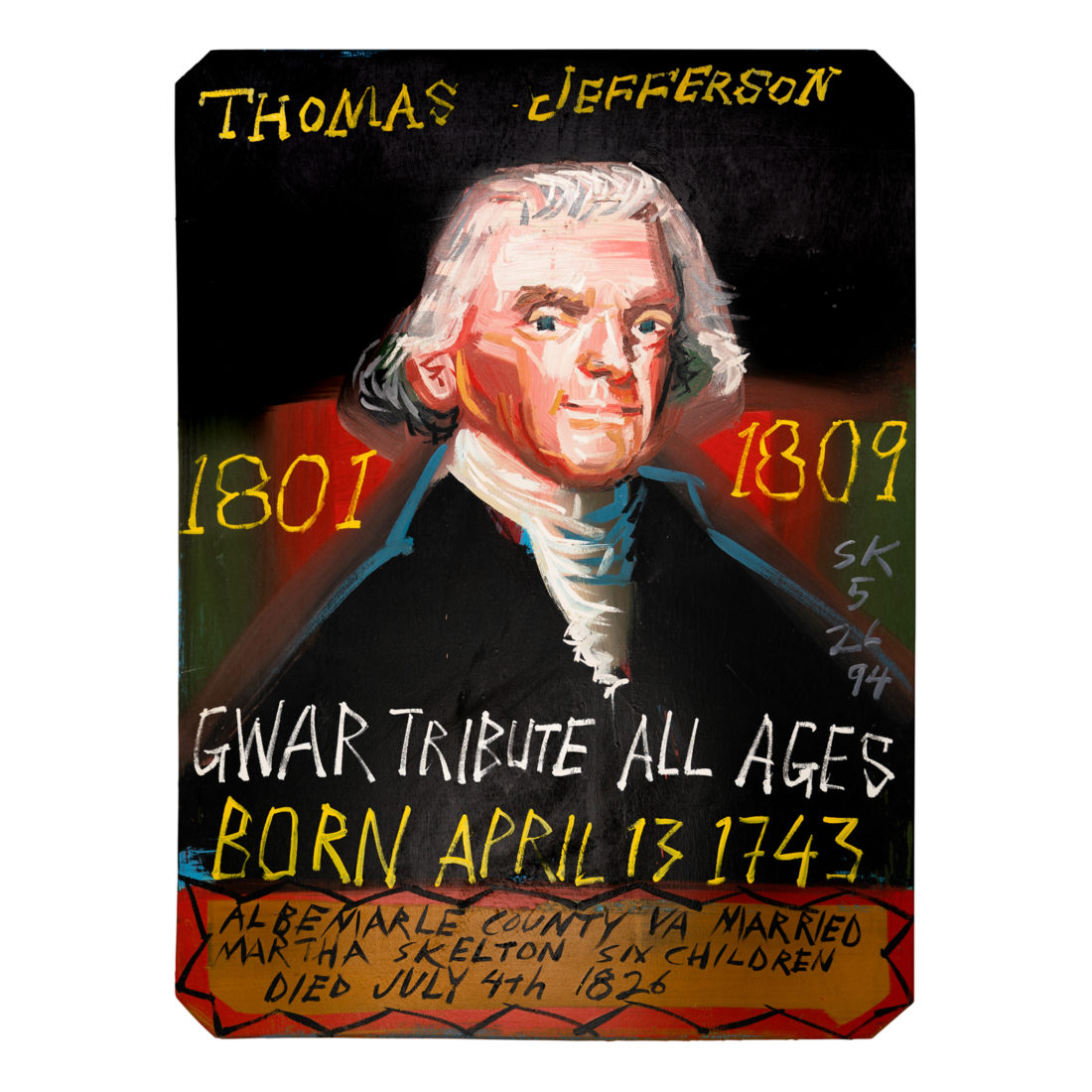

Thomas Jefferson, who has a strong cultural influence in Virginia, is a figure who comes up in your work. What draws you to these historical characters?

I was never interested in history, but it was a way to process where I came from, and it was a bridge to stuff my parents liked; they collected all kinds of collectible objects. The historical portraits are a homage to them and growing up in Virginia and Charlottesville.

You’ve compared your work to “diary entries.”

I look back on my work as a very personal job, one that I invented. My individual paintings are the residue of how I spend my day, since I’m painting every day. My style looks the same as it did thirty years ago, but I can tell differences in when something was made, like when I used fatter brushes or worked with more yellow. I used to paint my pets, but I try not to make paintings that I’ll like more than others—if I do personal stuff, I’ll feel sentimental. For me, it’s important to keep consistency.

You sell a mystery package of six paintings on your website. How do you choose which six paintings to send to someone?

I try to make them different: I mix in historical paintings with landscapes and portraits to give it a range. No one has complained yet, and I’ve sent thousands of these packages out. The idea someone would send you money in the mail and not know what they’re getting is a special bond of trust.

How do you know when a painting is complete?

I’ve always worked in restaurants, so I was always under the gun, timewise. I liked having time limitations; it made me think differently and intuitively. I would start a batch of paintings in the morning, and then I’d have to go to work at night. They would have to be done in that time frame. It’s like I’m working in a restaurant, preparing something to go out in the world.