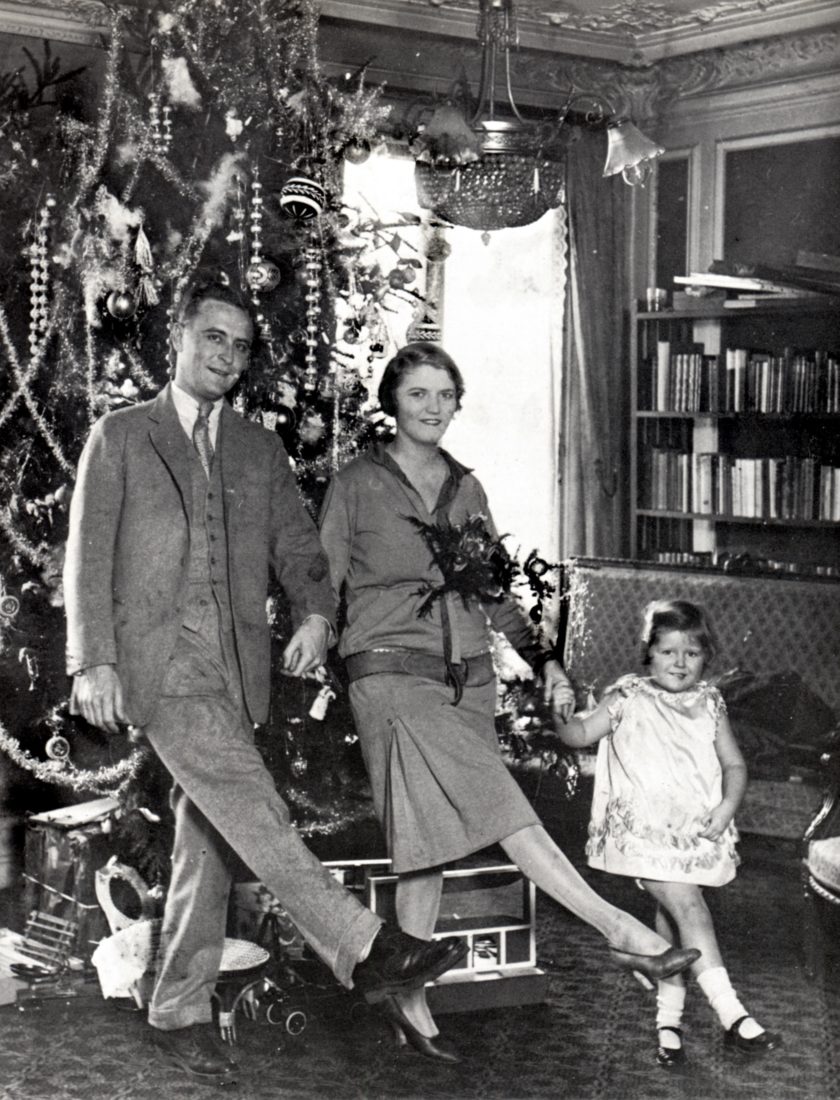

Zelda Fitzgerald earned her place as a cultural icon. Born and raised in Montgomery, Alabama, she was the face of the flapper movement of the 1920s, a socialite that roamed from Paris to the South of France to Italy. She lived alongside the literary fame and fall of her husband, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and her battles with mental illness and schizophrenia are well documented.

What should not be lost, however, is that while Zelda lived a life of great adventure and zeal, she also lived a life filled with tremendous creative energy. She turned to dance in her late twenties, an age when most dancers would be nearing the end of their careers, and was even offered a solo in an Italian ballet. She is the author of the novel Save Me the Waltz, which delves into the arduous training and complexities of the life of a dancer. She painted. She drew. She wrote poetry.

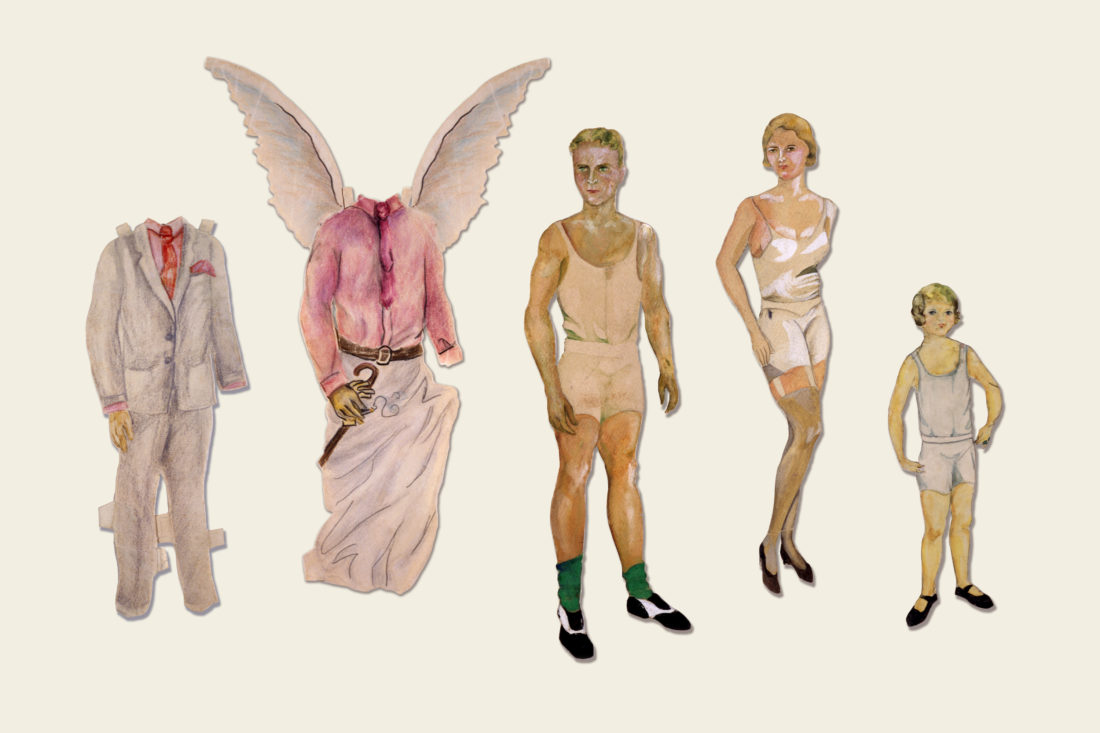

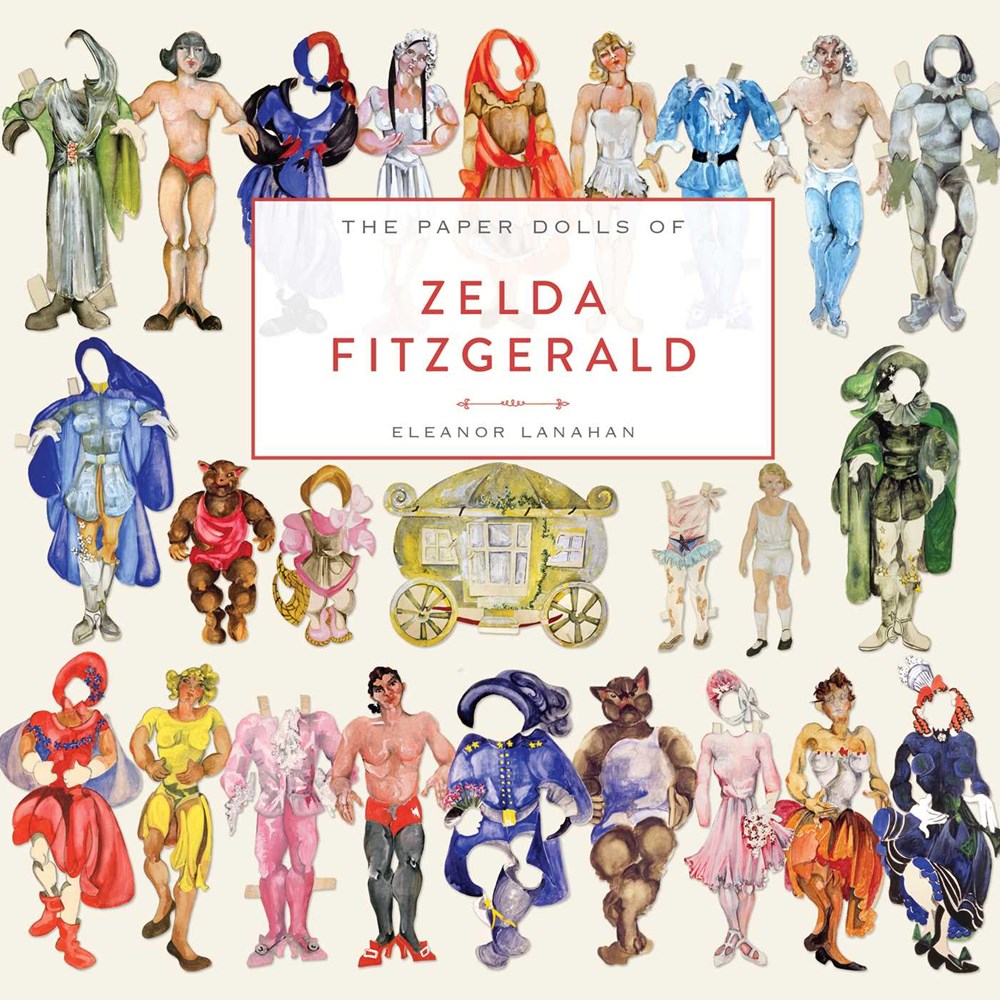

And she created paper dolls. But not just ordinary paper dolls. Paper dolls rich in artistic style. Paper dolls that depict characters from history and from fairy tales and favorite stories, complete with multiple costumes and the attention to detail that only a true artist can deliver. The practice, which began as a project to create dolls for her daughter, Scottie, grew into a great collection over the span of almost two decades. Now, a hundred years later, these dolls have been collected by Zelda’s granddaughter Eleanor Lanahan in a new book, The Paper Dolls of Zelda Fitzgerald, an extraordinary look into the art and vision of the famous Southern Belle.

I, like many Southerners, and particularly like many once-upon-a-time expatriates, have always been fascinated by the Fitzgeralds and their place at the center of the Lost Generation. So fascinated that the feelings of wanderlust and bewilderment in the heart of The Great Gatsby led to the creation of Nick, my most recent novel, which tells the story of Nick Carraway, the famous narrator of Gatsby’s story.

So it is not surprising that the collection of dolls is striking to me. There is an androgyny to the dolls, a sensibility that fits right into the changing notions of sexuality and gender that pervaded the uninhibited bars and streets of Paris in the twenties, the same bars and streets where Zelda roamed. The Three Musketeers are pretty. Goldilocks possesses muscular arms and legs.

The dolls almost seem like sculptures. The features are distinct, particularly the eyes and mouths, and the build of the bodies seems to gather notions from the famous sculptor Auguste Rodin, as the limbs do not seem static and flat but instead suggest physicality and movement. The definition of muscles and cheekbones gives a three-dimensional quality. The specific cut of King Arthur’s armor or the frills of Red Riding Hood’s bonnet add an individuality to each doll, their own voice and personality, which a mother and daughter could dive into during play time. And the costumes, of course. Each doll has multiple costumes, elaborate and fancy and made for parties. No doll of Zelda Fitzgerald could possibly be underdressed during the course of a tea party.

An introduction to the collection, by Lanahan, reveals that Zelda seemed to know she had created something unique over the years. In 1941 she wrote to Maxwell Perkins at Scribner, the famous editor of both Fitzgerald and Hemingway, that she would like to publish a book of paper dolls: “I have painted…King Arthur’s round table. Jeanne d’Arc and coterie, Louis XIV and court, Robin Hood are under way. The dolls are charming…Would you be kind enough to advise me what publishers would handle such ‘literature’ and how to approach?” No book materialized—until now. And it’s fittingly published by Scribner.

Zelda seemed certain that these were not just paper dolls, but true works of art. And they are. This collection is a fascinating look into the seed of creation, how a mother hoping to entertain her child could create with such imagination and skill. Perhaps the practice may have been as much for Zelda as it was for Scottie.

Michael Farris Smith is a Mississippi writer whose work includes Nick, a novel that imagines the life of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s protagonist Nick before The Great Gatsby.