Whenever snow falls, I don’t think first of boots or mittens or hot chocolate, or even of rummaging around a cold garage to find a beat-up piece of cardboard to use as a sled. I think of my grandma, and of snow ice cream—that concoction of powdery snow, milk, sugar and vanilla that tastes like a stolen school day in a bowl.

I was probably seven years old when I first learned about snow ice cream. It was two-thousand-and-something, and my dad had seen a winter weather forecast for Jonesboro, Arkansas, bad enough to make him jump in his car and drive the two hours to fetch his mother, who lived there, and bring her to the more southerly haven of Little Rock, which would be experiencing milder conditions.

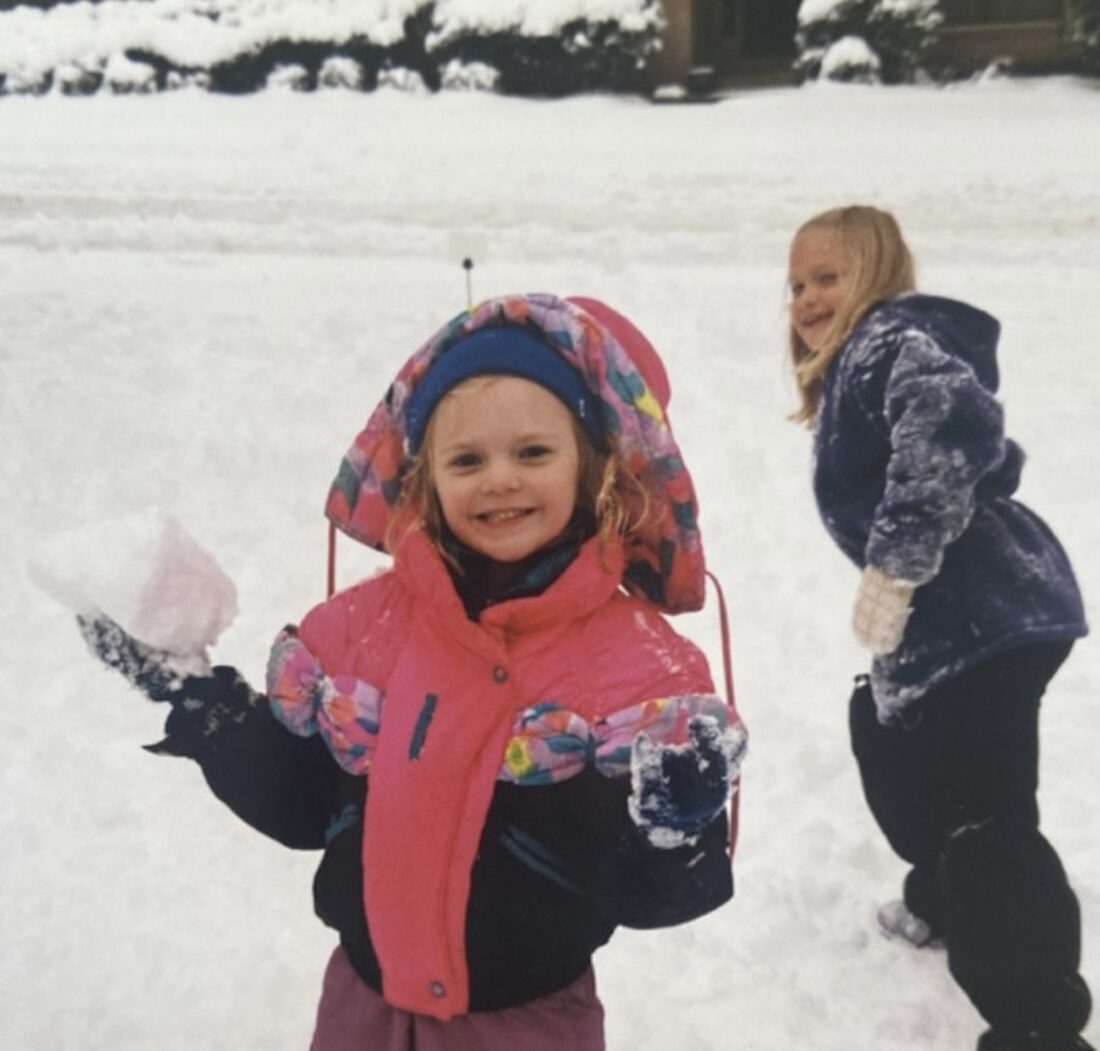

My grandmother, not a woman who ever needed rescuing, arrived just in time for Little Rock to receive a full blanket of ice and snow (Jonesboro was perfectly fine) that would keep her with us for days. Never one to sit around, she soon summoned my sister and me for a lesson in the making of snow ice cream.

I can still recite her guidelines of gathering. The snow should be from the second snowfall of the year or thereafter, due to air pollutants sullying the first (this is the only rule I’ll break). It is to be gathered carefully from the middle of a drift; the top layer could be contaminated, and the bottom layer is definitely contaminated. The gathering surface should be in an open area where the snow has fallen unobstructed. The concrete of a deck or patio is ideal, since there’s less possibility of dirt mixing in; if enough snow is piled on a metal railing, that can work, too. Any speck of anything is to be avoided—the snow must be the purest white.

For that first batch, my grandma trundled out into the cold herself to pile the snow in a big mixing bowl, then brought it into the kitchen to work her magic, without measuring: a few splashes of milk, a generous sprinkling of sugar, a teaspoon or so of vanilla, and a quick stir. She tasted it herself to confirm it was just right, then heaped it into two bowls, one for me, one for my sister. Immediately, I loved it—it was sweet and slushy-like, delightfully cold, the snow day brought inside, with the subtle caramel-y, comforting notes of the vanilla making it seem like a real dessert.

On the snow days when my grandma wasn’t rescued from Jonesboro in the years that followed, my sister and I learned to make snow ice cream ourselves, putting far too much vanilla at first because we couldn’t believe that something that smelled that good couldn’t be used with abandon.

Eventually we got the recipe down, and every Arkansas snow day we made it faithfully. One year, inspired, we decided to save snow in containers and freeze it so we could have snow ice cream year-round, whenever we wanted it. That didn’t pan out—the snow was the wrong texture and the flavor came out funny. We knew then what I’m sure my grandma could have told us: The magic of snow ice cream is that it’s as fleeting as its star ingredient.

To make a batch: Gather the snow into a large bowl (perhaps the same you use for popcorn) and add about ½ cup of sugar and a ½ cup of milk. The actual amount of milk will depend on the texture of the snow and your desired consistency (I like mine slushy-like). Then, shake in about 2 teaspoons of vanilla and stir.

Lindsey Liles joined Garden & Gun in 2020 after completing a master’s in literature in Scotland and a Fulbright grant in Brazil. The Arkansas native is G&G’s digital reporter, covering all aspects of the South, and she especially enjoys putting her biology background to use by writing about wildlife and conservation. She lives on Johns Island, South Carolina.