When some people remember the dogs in their past, they remember play and affection and hunting trips. Me? I remember a felon. Max, we called him. He started out with promise but in a few swift years evolved into a lean, one-eyed, battle-scarred epileptic, with a record of time served and a list of enemies earned.

Time erodes memory, and certain details of Max’s crime spree are lost to the decades. When exactly was he born? No one can say. It was the mid-1970s, and our parents had decided that our family was due for a dog. So we drove one day in the station wagon to a veterinarian’s office outside of Binghamton, New York, where we lived. There the vet—we called him Doctor—ran a small kennel. The Doctor sold puppies cheap: ten dollars a head.

In a stinking room, boxed off with fencing into separate cells, were scrums of small, yipping dogs. Among them was Max—a skinny mixed-breed hound, mostly black, with a whippy tail, a white neck, and brown spots above his dark eyes. He had an underbite on one side, which gave him a world-wise air, as if he had already done time. And he could leap—higher than the other dogs competing for attention. We selected him immediately, struck by his electric energy. He was also small—destined not to top thirty pounds, but rippling with muscle, even as a pup. He seemed the canine equivalent of a lightweight boxer. This was the first of many deceptions. Max had not, we would learn, acquired the build of a disciplined prizefighter. He had the rough-hewn frame of the inmate, the reprobate training for escape.

We brought him home.

My father had been raised with hunting dogs, and later, because his father had been blinded in a hunting accident, he had lived with Seeing Eye dogs, too. He expected rules. Rules were imposed. Max could not venture upstairs. He could not put a paw on furniture. He was quickly house-trained. Binghamton had a leash law, and a dogcatcher, and so Max was expected to stay home, fenced in the yard except when out with the kids, when he was to be kept close.

Like many rules, all of these sounded sensible on Day One. But a home is no Alcatraz. Any notion of confining Max faced a reality: Max. Our yard was fenced. Max dug under the fence and roamed. We retrieved him each time, sometimes after hours, other times after days. A new plan was found. We would drive a stake into the soil and tie him to it, with perhaps twenty-five or thirty feet of play. Max briefly puzzled through this new form of confinement, wearing the grass into mud. Then he forced his will upon his circumstances and bent the world back to his command. First he pulled up the stakes, even corkscrew-shaped stakes twisted into the soil. Again and again he ran free, dragging a rope behind him. We kept trying. So did Max. One day, he ended any notion of confinement by chain or rope. After tying him to a post, we returned home to find no dog. Instead, the rope was leading up over the six-foot stockade fence. This was a chilling moment for a boy aged ten or twelve. My dog, it seemed, had hung himself. He was a prison suicide. But when we scrambled to the property line and looked down into our neighbor’s yard, we found only his collar hanging there, in the air, several feet above the ground. Max had slipped through and dropped to the opposite side—gone.

If the yard could not contain Max, neither could the house. To each of us, Max was a delight—a deeply affectionate friend, a rascal with charm. But he was his own dog, and if he drew physical and social sustenance from us, he communed as well in another world. He was, and let’s be clear, an animal more comfortable in the animal realm. We, it seemed, were the bandit’s safe house. He would run himself hard outside and come inside for food and sleep. Sleep was sometimes one of his many deceptions. When Max was ready to go outside, he was ready to go outside. When we opened the door—say, to check for mail, or to head to school—he would dash past our shins with an athleticism and determination that bordered upon maniacal. Sometimes we managed to catch him as he exploded past. But usually our hands slipped off of him as if he were a greased eel.

Once outside, Max was the real Max. It was not pretty, and those who lived near us must have thought us mad. He raided our neighbors’ garbage, knocking over cans and scattering scraps. He hunted anything smaller than himself. He leaped into the air to snatch flies with a snap of his snout. Once we saw him attack a nest of yellow jackets. (Let’s just say he was enthusiastic, clever, and addicted to an adrenaline buzz. None of this should be confused with smarts.) He strutted past the fences that confined the neighborhoods’ other dogs, and taunted them. But eventually Max would grow bored and walk away, the unconfined prince of Johnson Avenue. What are you going to do about it? This could not end happily, and it didn’t. One day he staggered home one-eyed, having been chased off a lawn by a neighbor swinging a rake. The Doctor sewed him up, and soon epilepsy set in, apparently from the head trauma. Nighttime seizures became an occasional routine; we moved aside the furniture while he twisted and rolled. After a few minutes, the seizures would pass. Max would be Max again, trying to get out.

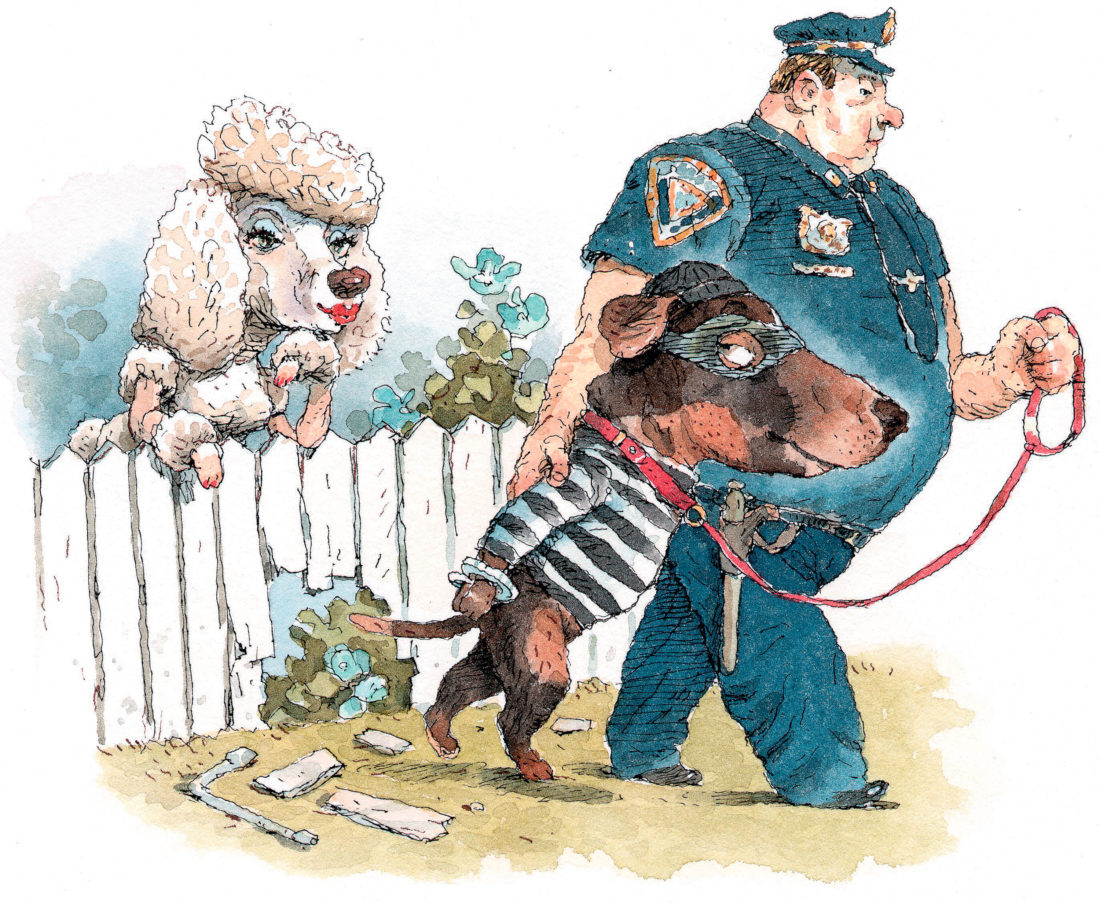

Neither food nor hunting was enough for him. Epilepsy and limited vision did not dampen his wilder impulses. Besting bigger dogs was only a game. A fuller account must be honest: Max wanted sex. For it he prowled the entire town. Sometimes we would spot him miles from home, moving swiftly, with a drive only he could explain. We would retrieve him, and he would try again his domestic life. But he was a soul on parole, and his presence in our house never lasted. Always he would bolt. One neighborhood dog, Moxie, was almost endlessly in heat, and Max cycled though her affections each spring and fall. The city dogcatcher knew Moxie, too, and he regularly trolled through the crowd of male dogs that assembled where she lived. These were usually the times Max ended up in the pound. We had a rough sense of the timing. If Max was gone two or three days, no need to worry. After four or more days, we could visit the pound and find him there, covered in fleas, contemptuous in his cell with his underbite and one-eyed leer, ready for my parents to pay the fine and forgive.

As Max broke down the rules, we grew lax. What was the point, exactly, of trying to chain a dog in the yard if he simply climbed the fence and jumped into the air? And how could you contain a dog that pretended to sleep, biding time for a crack in the door? The answer was: We couldn’t. We didn’t. We failed.

And sometimes our math was wrong. One time Max vanished for several days, and he was not at the pound. Moxie was in heat a half block away, and the usual crowd milled on her lawn. We were stumped. Max would not have headed to another side of town with his date waiting nearby. So where was he? Several walks past the neighbor’s house turned up no clue. Then came the breakthrough. While walking past Moxie’s home and once more scanning the crowd of desperate-looking dogs for mine, I heard Max. His bark was distinctive. But he seemed to have made himself invisible. He could be heard but not seen. I called for him. He answered back. I called again. He answered again. I ventured onto the lawn, nearer to my neighbor’s home, and at last the latest in Max’s misadventures was revealed. A basement window had been broken and a piece of plywood fitted over the open pane. This had been pushed aside, allowing a shaft of light to fall into the gloom. I poked my head near and looked down. There, looking up, was Max, giving me his one-eyed, where-have-you-been stare. Moxie, his exhausted concubine, was lying on her side beside him, panting. A few minutes later, I was explaining to the neighbors that my dog had plunged through their basement window and was in residence in their cellar, impregnating Moxie, whom they had responsibly kept inside. Max came home for another brief stay. He needed, if nothing else, to catch up on sleep.