When he drives along the flower-lined back roads of the Alabama Black Belt toward his house in Greensboro, Aaron Sanders Head doesn’t see weeds. Queen Anne’s lace looks like summer, and the first bright blooms of goldenrod bring with them fresh inspiration. Head’s artwork, made from secondhand textiles and dyed with botanicals he forages and grows, ties him to the land in ways both literal and mystical. “Anyone who spends their time in the Black Belt,” he says, “knows this is a beautiful, radical place, brimming with so much life.”

Originally from unincorporated Grady, Alabama, Head grew up close to both agriculture and craftsmanship. His father, who worked at Bonnie Plants and built greenhouses, and grandmother, an avid gardener, taught him about native flora. His maternal grandparents toted him along their routes as rural mail carriers, and he often learned at the feet of his mother, an artist herself. His childhood fostered a love of noticing—of weaving together the natural world and the stories of the neighbors who live within it.

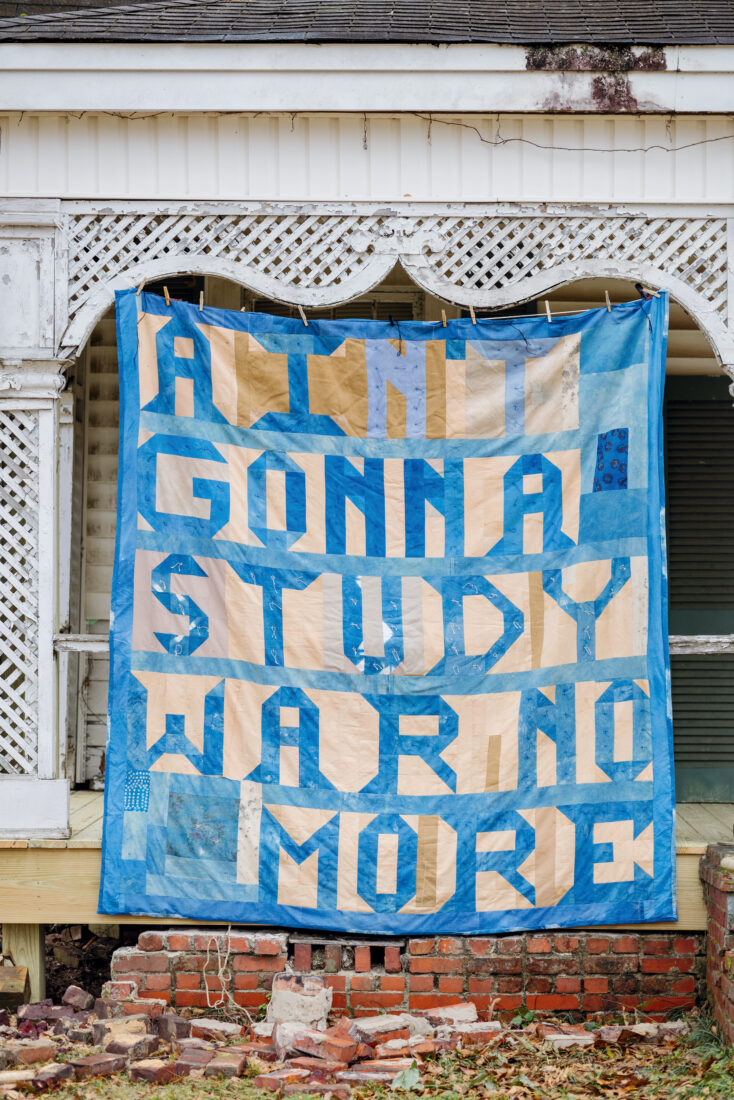

Head’s work is audacious and yet subtle, using the commonplace to communicate messages about life’s big questions. He sewed his quilt ain’t gonna study war no more in peaceful blues and creams, hand dyed from indigo and black walnut. It hung last year at the Kentuck Art Center & Festival in Northport and explores the act of reconciling, using the language of stitching, piecing, and mending.

Since textile work immediately feels familiar —who doesn’t have a favorite blanket or relish the comfort of a crisp cotton sheet?—Head is committed to making art that looks like the place where it was made. “When I moved to Greensboro and people found out that I created my pieces exclusively from previously owned materials, I started receiving donations,” he says. A great-aunt’s cloth napkin, many years forgotten in a drawer, for example, might now have a second life in his newest work.

Head also teaches foraging workshops and dyeing classes to connect people to their surroundings. After years of renting studio space, he recently purchased one of Greensboro’s neglected but lovely architectural treasures: Sumac Cottage. The nineteenth-century structure, set on an acre downtown, had only three walls, but Head is bringing it back from the brink. When it opens (in May, he hopes), Sumac Cottage will house his own studio and gallery, a shop, space for visiting artists, and a dye garden, seeded with indigo, marigold, madder, and goldenrod. The cottage’s covered back deck will play host to musicians, both regional and traveling.

Head is most excited for local residents to enroll in workshops, to take their place in the tradition of Southern artisanship. He hopes that the very neighbors who shared heirlooms to feed his work will attend weaving and painting classes, unearthing talents long buried or yet undiscovered. Because while others might fantasize about escaping a small town, Head’s idea of chasing a dream looks more like his childhood: slower, rooted. “I love where I live,” he says. “The idea of ‘making it’ in another imagined cultural capital? It’s just so much more interesting to me to figure it out here.”

Read more about the South’s new slate of artists, curators, preservationists, movers, and makers in Art’s Rising Vanguard.