The apparently indestructible Texan and Southerner Willie Hugh Nelson, born April 29, 1933, in Abbott, Texas, has gained his eighty-eighth birthday. To mark the occasion, there have been and will be quite some doings down in Luck, Texas, his seven-hundred-acre townlet-ranch/recording studio/bio-diesel-and-cannabis HQ in the Hill Country. But a deeper sort of salute is in order. The octogenarian has been producing his special brand of shoot-from-the-hip outlaw country/jazz fusion for so long that we’ve simply come to expect that each year will bring another Nelson album. Are the azaleas showing yet? Then Willie should be along just any minute now with another LP.

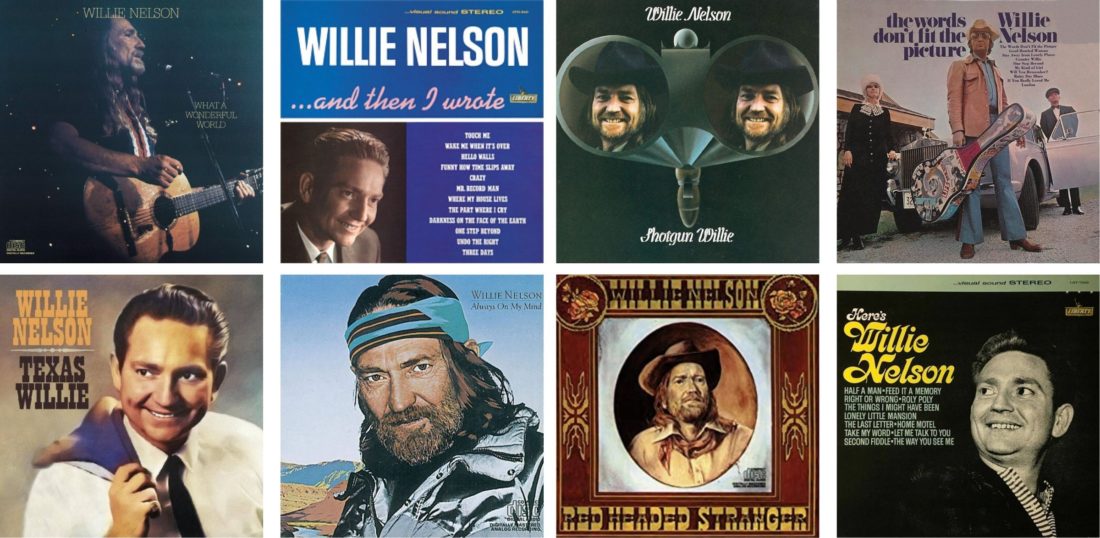

As Willie’s millions of fans are aware, his 2021 record That’s Life—his second album-length tribute to one of his prime influences, Frank Sinatra, dropped back in February. Yep, that’s right: The platinum-selling country artist and seriously jazzy guitar picker counts not just Sinatra but also—as scholars and aficionadi of all things Willie can testify—the jazz giants Django Reinhardt and Louis Armstrong among his chief musical forefathers. It makes perfect sense. It’s why Willie’s first Sinatra tribute album, My Way (2018); his pop standard albums, including the iconic Stardust (1978); his Armstrong tribute, What A Wonderful World (1988); his tribute to the Gershwins, Summertime (2016); as well as his collaboration with Merle Haggard on their 2015 tribute album to Django Reinhardt and Jimmie Rodgers, got cut.

We can be forgiven for thinking of Willie as a country, or even as a “Texas” musician. He is that, but his bleak songwriting and kaleidoscopic picking are just too restlessly protean to have been cubbyholed at any time in his life. Of the many metaphors that could fit this man, perhaps the best is one of the Texas range: Musically speaking, Willie is pre-barbed wire. There are no fences in his hands or in his mind.

And that was his problem in Nashville during what we might call his “first” career in Music City in the sixties. The producers swathed him in lush string arrangements, and he obliged by slicking his hair back in a pomp and strapping on a regulation jacket and tie. Shockingly, he actually shaved. None of it stuck: He was just way too “Willie” for the folderol.

Having simply stopped off in Nashville to sell a couple of songs, by 1964, Willie nevertheless attained success—he was a member in good standing of the Grand Ole Opry and he’d already written the century-spanning hit “Crazy” (Willie’s demo tape of which Patsy Cline’s husband, Charlie Dick, instantly took to his wife, who promptly agreed to record it). But Nelson didn’t fit into the Nashville of the 1950s and 1960s for a different, more radical literary and musical set of reasons. Put specifically, “Crazy” transcends its accidental genre of country because, at bottom, it’s not a country song. It’s a Willie Nelson song.

With apologies to all of Willie’s pure-country fans whose blood may be boiling about now, this simply means that Nelson writes songs that may sound “country” —they may give a nod to, or be, a Texas waltz, or they may be built on a blues progression or a stately God-fearing hymn—but in his hands, released on vinyl or on the stage, they then soar up into the American songbook, beyond genre, open to interpretation by artists from myriad disciplines. Over his nine decades and counting, his musical arc is as grand as it is because, like the Gershwins, Hoagy Carmichael, Louis Armstrong, Harold Arlen, or Rodgers and Hart, whose work he lovingly covers and quotes, Willie Nelson writes American standards.

He’s also a ferociously loyal, ornery-ass old cowboy, and on his birthday, we’re grateful to him for that, too. He carries his best songs with him forever, he simply will not lose them, deepening his relationship with them as he would a set of old friends.

The paradigmatic composition, which also serves as an early statement of Nelson’s infamous “outlaw” status, is the incisive love song “I Never Cared for You.” The progression begins with a forbiddingly dark A-minor chord. Everything about Nelson is in this work, beginning with his long guitar improvisation, effortlessly quoting Django, flamenco riffs, and, if you listen hard, there are whiffs and traces of classical transcriptions by Andres Segovia. With its big, broad fretboard, Nelson’s battle-worn Martin classical N20, named for Roy Rogers’s horse Trigger, helps this furious solo along by being an American cousin to the Spanish guitars.

But it’s the dramatic structure of “I Never Cared for You” that gives it the power to have become a standard. The song is an attempt by its narrator to tell his mistrustful beloved that he knows she won’t believe a thing he says, thus he will tell her he loves her by saying the opposite, so that she will disbelieve that. The refrain says it all, with winning bleakness:

The sun is filled with ice and gives no warmth at all

And the sky was never blue

The stars are raindrops searching for a place to fall

And I never cared for you.

The song is more than a little majestically Shakespearean—it could be sung to Kate in The Taming of the Shrew with zero changes to the lyric, and it will effortlessly stand up in the American songbook for the next few hundred years. Needless to say, this dark, brainy, loving, tragic, and ironic joust—more at a Hoagy Carmichael/Cole Porter level—was widely hated in early-sixties Nashville, and promptly tanked. Nelson wasn’t bothered. He carried the song with him. Backed by Emmylou Harris, it soars brilliantly in his hands on his 1998 album Teatro, produced by Daniel Lanois.

For some years, Nelson’s face has been that of a rogue president somehow missing from Mount Rushmore, big beak, cheeks all crag and fissure, framed by the long Plains Indians braids. His voice now carries a whiff of tremor that can still be mastered to open clearly, and the tremor’s travel down through the broad gravel path of his voice brings another dividend of countrified hurt to the recent ballads. His command as he sings is peerless, and his picking only grows sharper and more deep. For six decades, his athletic discipline has been martial arts, kung fu since the sixties in Nashville, and he’s now a second-degree black belt in tae kwon do, a rarity among the octogenarian set.

He makes his mastery seem like an offhand cowboy happenstance, but pretty much everything Willie Nelson does is rare and, after seventy-one studio albums over sixty years, he is among us. At his eighty-eighth, that is worth celebrating.