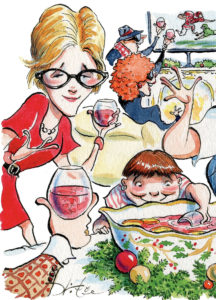

More than once, when writing about the holidays, I have quoted the ever-reliable Oscar Wilde: “After a good dinner, one can forgive anybody, even one’s own relatives.” There is no question that the food is important. A chopped black truffle or two studding the mashed potatoes, say, or even a really good squash casserole, can go a long way toward repairing frayed nerves. Conversely, an overcooked rib roast or the wrong kind of pie can be the potentially dangerous last straw. One year, my grandmother’s Christmas rolls were so hard that my grandfather threw one down the table at her, sending it splashing into the gravy boat. Since then, I’ve learned to hedge my bets with Sister Schubert’s fail-safe frozen yeast rolls, along with copious amounts of festive refreshment, a strategy I’m sure Wilde would have wholeheartedly supported.

The point is that after enough punch, people tend not to care, or even notice, that the rolls haven’t risen, that little brother’s girlfriend has a nose ring (or five), that some of the people assembled haven’t actually spoken a civil word to each other in more than forty years. This is pretty much the theme of Robert Earl Keen’s infectious and spot-on anthem, “Merry Christmas from the Family,” which starts out with the line “Mom got drunk and Dad got drunk at our Christmas party.” Of course they did. The song is populated by ex-wives and new wives and irritating cousins and boyfriends and other members of the extended clan that most of us try to avoid until the holidays inevitably roll around and we are forced together in the name of some misguided family unity.

Keen’s crowd makes the best of the proceedings by drinking champagne punch, homemade eggnog, margaritas, and Bloody Marys (“cause we all want one!”). In between, there are numerous trips to the Stop’n Go and the Quick Pak store for everything from Salem Lights and a can of fake snow to a bag of lemons and some celery for the aforementioned Bloodies. While I too am an errand-running fool during the holidays (what better way to appear useful while also getting the hell out of the increasingly fraught house), I am not so ambitious with regard to the drinks. Punch or eggnog, followed by the best wine you can afford, should do it. For one thing, an elegant silver punch bowl puts the sheen of propriety on the fact that what you’re really serving up is a big batch of holiday denial.

Made the old-fashioned way, punch is also, to quote one of my father’s highest compliments, “strong stuff.” When he uses the term, it’s usually in reference to a good-looking woman or an especially funny anecdote, but I’m sure it derives straight from the punch bowl. Cocktail historian David Wondrich explains that punch was the forebear of the cocktail, originating in sixteenth-century India, where it was some rough wine “drowned” with sugar and lemon and spices, and augmented with stronger spirits and lots more citrus once the Brits made it to India and beyond. No matter where it ended up, Wondrich says the punch of the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries bears about as much relation to the anemic stuff served at today’s teas and banquets as “gladiatorial combat does to a sorority pillow fight.”

Consider, for example, the Savannah Junior League cookbook’s recipe for Chatham Artillery Punch, which calls for a gallon of gin, a gallon of rye, a gallon of cognac, two gallons of rum, two gallons of Catawba wine, and twelve quarts of champagne. The punch, long a point of Savannah pride, was the house brew of the city’s all-volunteer regiment, founded in 1786 and described by Wondrich as “a Social-Register militia…that spent far more time parading and partying than it did loading cannons and shooting them.” Which might have been just as well. In 1883, a Georgia journalist wrote of the punch that “we are living witnesses to the fact that…when it attacketh a man, it layeth him low and he knoweth not whence he cometh or whither he goeth.” One way to get rid of one’s peskier relatives, I suppose, would be simply to kill them with the stuff. Or you could give them a couple of cups and watch them kill each other. When Wondrich whipped up a batch for a recent food and wine festival in Atlanta, he warned the participants, “I have seen bad things happen from drinking this.”

Savannah is not the only Southern city whose punch recipe can be put to good holiday use. Charleston’s militia had a punch too, the Charleston Light Dragoon punch, a delicious version of which, containing brandy, peach brandy, and Jamaican rum, is served at Sean Brock’s irresistible Husk.

Then there’s the city’s St. Cecilia Society punch, another variation on the classic brandy, rum, tea, and champagne mixture that’s always served at the annual ball of the august society, formed in 1766 and named for the patron saint of music. In 1896 the Baltimore Sun reported that there is “no social organization in America so old or so exclusive” and that the balls are “characterized by dignity.” Maybe so, but after the only one I ever attended (a boarding school running mate was being presented), I woke up with a date on a park bench in an evening gown and missed two airplanes out of town. As a result, I prefer the slightly more refined punch recipe given to me by my friend Lynn Steiner from Montgomery, Alabama, where it is something of an institution. First published in the cookbook of the local Episcopal Church ladies, it consists mainly of champagne, Sauternes, and brandy, and is especially pretty with a decorated ice ring.

But then even the roughest punches can be things of beauty. My hero Charles H. Baker, Jr., the professional bon vivant, world traveler, and occasional drinking buddy of Ernest Hemingway, gets borderline teary-eyed over the “Ritual of the Punch Bowl” in the Exotic Drinking Book volume of his seminal Gentleman’s Companion: “Few things in life are more kind to man’s eye than the sight of a gracefully conceived punch bowl on a table proudly surrounded by gleaming cohorts of cups made of crystal or white metals, enmeshing every beam of light, and tossing it back into a thousand shattered spectra to remind us of the willing cheer within.”

Baker’s book contains an extensive section on punch, but there’s mention of eggnog too, specifically one considered a “Scottish institution” (who knew?) from the Clan MacGregor, “a lovely, forceful thing based on brandy, Bacardi, and fine old sherry.” I was never a huge fan of eggnog, from Scotland or elsewhere, preferring the milk punches that are ubiquitous in New Orleans, where I live. But that was before I tasted the version made by my friend Mimi Bowen, who grew up in Memphis and who owns a fabulous New Orleans boutique that bears her name. The recipe comes from Mimi’s grandmother and namesake Myrium Dinkins Robinson via her aunt, Lynn Robinson Williams, whom Mimi calls the “Auntie Mame of Memphis.” Aunt Lynn, who died in her bed on her ninety-sixth birthday with both a cigarette and a glass of champagne in hand, sounds like someone I would’ve actually enjoyed spending the holidays with. Well into her eighties when she finally passed the recipe along to Mimi, she put it in the mail with a note reading, “For your file. Don’t lose it.” I reprint it here exactly as she typed it.