We might be drinking in the last dregs of summer, but for at least one beach activity—shelling—the next few months bring the glory days. Beaches are less crowded, autumn storms roil the surf to dislodge more seashells, and shell seekers won’t melt in the equatorial heat that descends on Southern beaches in the summer. While there’s nothing wrong with a pail full of cockles or a pocket stuffed with lettered olives, a few shells are particularly coveted for their rarity and beauty. We’ll call these the Holy Grails of Southern beachcombing. They’re just this side of impossible to find, so first, get your mental search engine dialed in. Then assume the unofficial pose—hands clasped behind your back, half bent over—and make it a mission to discover at least one of these three before you have to don a puffy jacket every time you leave the house.

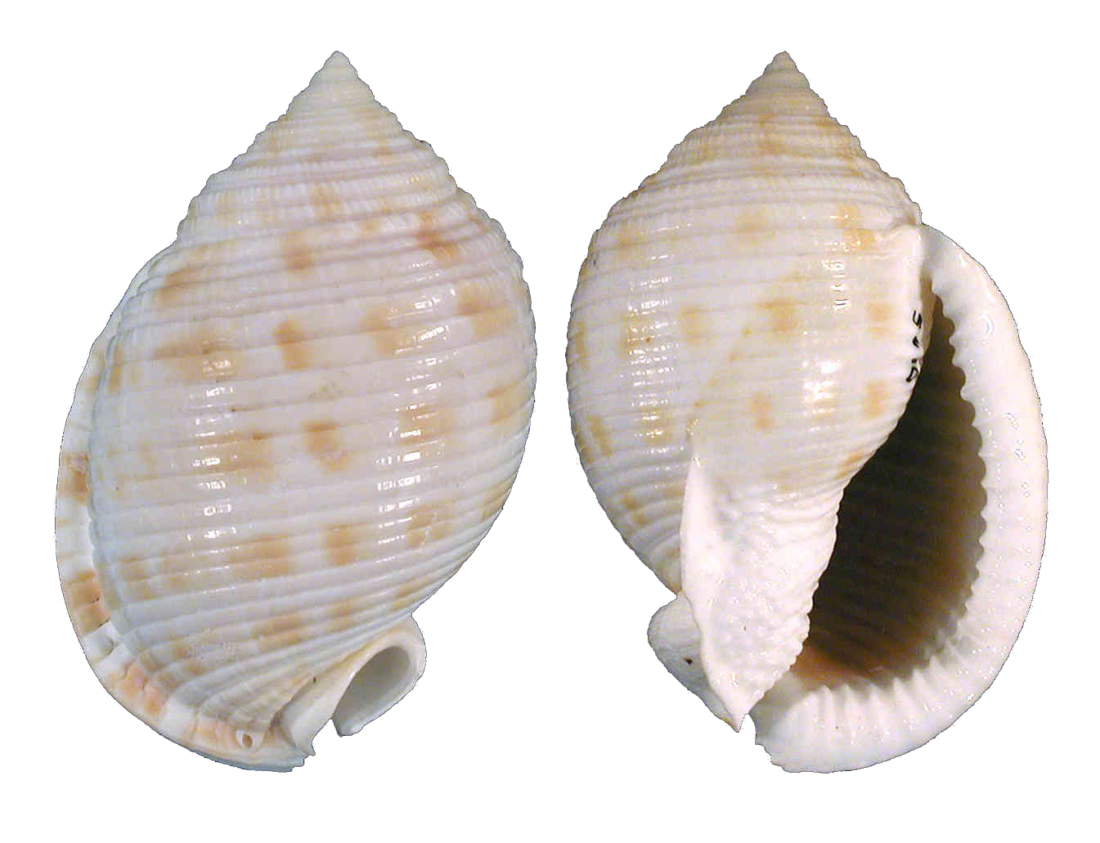

Scotch Bonnet

I have never found an intact Scotch bonnet, despite the fact that it’s revered enough to carry the status of official state seashell in my native North Carolina, and that I spend a good chunk of my beach time at Cape Lookout, a purported Scotch bonnet hot spot. The only time I’ve ever seen an intact Scotch bonnet discovered in situ was when I was shell hunting at Cape Lookout with my friend Kevin, grousing about my Scotch bonnet curse, when he bent over and picked up a perfect specimen. “Is this one?” he asked.

Yeah, Kevin. That’s one.

The Scotch bonnet gets its name from its shape, which (very) vaguely suggests a Scottish tam o’ shanter hat. I think it more closely resembles an egg with a pointy tip. It is frequently checkerboarded with orange-brown spots, and scored with incised lines that neatly mimic the whorls. It’s an artful seashell, which belies the rather gruesome life history of Scotch bonnets. The gastropods feed heavily on live sand dollars and keyhole urchins, spreading over the hapless creatures like melted ice cream, excreting sulfuric acid to eat away at the prey’s body armor and expose the yumminess—to a Scotch bonnet—of the body tissues beneath.

You can find pieces of Scotch bonnets with hardly any trouble at all (and I have). And it’s not uncommon to spy a Scotch bonnet half-buried in the sand, looking perfectly intact, until you turn it over and discover that a chunk of the shell is missing. Such near-misses only deepen the hunger. Hope springs eternal, but I’m still not so over it that I’ve asked Kevin to hit the beach together.

Wentletrap

Also called staircase shells or ladder shells, wentletraps are formed of distinct tapering whorls held together by a series of sharp vertical ribs. There’s a lot going on in the sculptural, almost porcelain-like architecture of a wentletrap, especially considering its size. While some wentletrap species—there are more than six hundred—are larger, an inch-long wentletrap on Southern beaches is a whopper.

Like Scotch bonnets, the wentletrap’s lace-like fragility makes it difficult to find an intact shell, and belies the animal’s life history. The gastropods suck the life, literally, out of sea anemones, which makes shallow water near coral reefs a best bet for locating these tiny beauties.

Junonia

Unlike more common bivalves and gastropods, from scallops to whelks and conchs, the junonia lives in the deep. Found on the ocean floor in water between one hundred feet to four hundred feet, these spotted creatures—or more precisely, their shells—rarely make it to the dry sand beach. And they’re not likely to stay there long. The junonia is perhaps the South’s most coveted seashell.

Untold thousands of beachcombers hit the sand at the shelling mecca of Sanibel, Florida (home to the Bailey-Matthews National Shell Museum), each year, fingers crossed and back stooped, dreaming of an unscathed junonia but happy to find a recognizable chunk. The whorled, cream-colored shells wear a well-ordered splotching of brown dots, a camouflage matched by the living flesh of the creature.

Follow T. Edward Nickens on Instagram @enickens.