It was 1962 and Mrs. Gladstone Williams, Washington, D.C.’s doyenne of formal etiquette at the School of Protocol, was hosting a luncheon at the Willard Hotel. Known as the “high priestess of form,” Williams taught diplomats and members of Congress the particulars of politesse—be it calling card conduct or how to gracefully eat an artichoke—and her menus were an extension of her lessons in good taste. That afternoon: finger sandwiches, filet of lemon sole, and for dessert, the options of pineapple sherbert, pie du jour, or fruit Jell-O.

Today, Jell-O has more of an institutional reputation as a cafeteria and hospital staple—it has mostly slipped off its pedestal. But there’s a glimmer of hope: Jell-O might be on the cusp of a Southern restaurant comeback, at least if one Nashville rooftop bar, the new White Limozeen at the top of the Graduate Nashville hotel, has anything to do with it.

But first, how did we get here? Before jigglers and pudding pops, and, Lord help us, Jell-O shots, there was just jelly, an ancient form of preservation by means of cooking down collagen, the glue that holds mammals, birds, and fish together. Humanity’s gelatin love affair began as early as the Middle Ages with the discovery that this protein extract could preserve food suspended in it. Think early aspics, like those savory jellies packed with all manner of bits and bobs of meat and veggies. In the 1600s, clear collagen extract was the stuff of court legend thanks to clever servants introducing sugar to it. Then, in the 1700s, the spectacle really began: wild, gravity defying jelly molds featured astronomical subjects and castles in Elizabeth Raffald’s 1769 cookbook, The Experienced English Housekeeper.

When the gelatinous trend made its way to American shores, colonial trendsetter Thomas Jefferson served wine jelly at Virginia’s Monticello in special glasses—“21 cut & 3 plain jelly glasses” to be precise. The backbreaking work of rendering collagen for jelly, however, vanished in 1845 when Peter Cooper figured out a way to powder it, and in 1897, part-time chemist Pearle Wait and his wife May experimented with gelatin to craft a fruit flavored dessert and named it Jell-O. Through the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s, Jell-O was an American kitchen must-have with recipes like “Perfection Salad”—a celery-and-cabbage-packed dish—a weekly dinner go-to.

Jell-O was also popular in restaurants, including in the South. Fruit Jell-O with cream was on the menu at Marty’s Lobster House and at Arkansas’s Country Kitchen. In 1952, on a Miami-to-Havana overnight cruise aboard the SS Florida, travelers could enjoy Jell-O with a $3 bottle of burgundy. And even as the wiggly dessert began to fall out of fashion in the 70s, cafeterias like Piccadilly’s, K&W, and S&S were the hold-outs, serving cubed Jell-O in glassware for generations.

Jell-O-positive nostalgia inspired Marc Rose and Med Abrous, the restaurateurs behind Nashville’s recently opened Graduate hotel rooftop bar, White Limozeen. “When I was a kid and my grandmother would make me Jell-O,” Rose says, “it was the greatest day of my life.” Rose remembers the anticipation of waiting for his grandmother to step out of the kitchen carrying a fancy molded dessert followed by the sheer fun of eating her wobbly masterpiece.

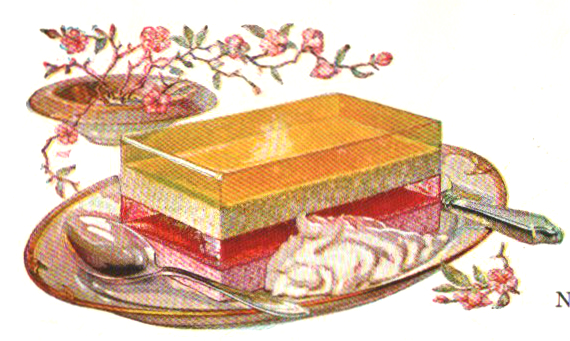

When he and Abrous began developing White Limozeen, which has a bright pink patio that one writer described as a real-life Barbie Dreamhouse (the name is actually a nod to Dolly Parton’s 1989 album, White Limozeen), Rose realized his Jell-O vision. “There are so many places we can go with it,” he says of Jell-O’s adaptability. White Limozeen’s $9 Jell-O dessert is a hypercolor three-layer confection stuffed with seasonal fruits such as peaches and coconut and plated with pink whipped cream and strawberries.

“The dish is exactly what White Limozeen is—beautiful but attainable for anyone,” Rose says. And highly Instagrammable. Based on its looks alone, the dessert might just be enough to get other restaurants back on board the Jell-O train. “I really believe in the world of Jell-O,” Rose says. “It’s funny. It’s a little goofy, but it’s also delicious. It’s like, why not?”

And while White Limozeen might be enticing a new generation to Jell-O, a handful of Southern stalwarts never left the stuff behind. K&W Cafeteria in Winston-Salem serves red and blue Jell-O; the Colonnade in Atlanta still dishes out tomato aspic; and Revel Kitchen & Catering in Fredericksburg, Texas, serves a towering vegetable terrine—signs that in the South, Jell-O jiggles on.