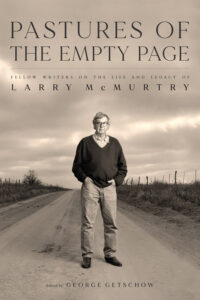

Editor’s note: The novelist Larry McMurtry was born in Archer City, Texas, and died there in 2021. His stories of the West, including Lonesome Dove and The Last Picture Show, are modern American classics, and in a new book, writers pay homage to his legacy. This piece is excerpted from that new book, Pastures of the Empty Page: Fellow Writers on the Life and Legacy of Larry McMurtry (University of Texas Press).

I was traveling through the northern part of Michigan with my friend Grahame Larson last summer. Dr. Larson is a professor of geology (emeritus) at Michigan State, and as we drove down the coast of Lake Michigan, he pointed out the glacial cuts, the sand dunes, the cigar-shaped hills (called drumlins) that define the shore.

That led me to ask him about north-central Texas, where I would be going in a few months for a celebration of the life of Larry McMurtry. He told me that a long time ago—six hundred million years ago—north-central Texas was covered by marine waters.

“And what about Archer County?” I asked, describing its location near the Oklahoma border. “Have you ever heard of Archeria?” Graham replied. It turns out that Archeria was an aquatic predator, with chisel-shaped teeth, that flourished 210 million years ago in Archer County—hence its name, Archeria.

The work of writers is often shaped by the terrain in which they were raised. Down where I live in coastal South Carolina, the novelist Pat Conroy wrote, “The island land where I grew up was a fertile semi-tropical archipelago that gradually softened the ocean for the grand surprise of the continent that followed.”

Hemingway similarly found material for his first stories in northern Michigan, where he spent his teenage summers: “They stood together, looking out across the country, down over the orchard, beyond the road, across the lower fields and the woods of the point, to the lake.”

In the same way that Pat Conroy studied and assayed the landscape of South Carolina and Hemingway that of northern Michigan, Larry became the master geologist of Archer County, peeling back the surface of the land and its history, layer by layer, in both his fiction and his nonfiction. “Most of our pastures consisted of rolling country—from the rises and ridges of all of them I could see Archer City,” he wrote in Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen: Reflections at Sixty and Beyond. He said the effect was reminiscent of a Thomas Hardy novel. “The village or manor, where we returned every night, was never long out of sight.”

Larry didn’t populate his landscape with the marine amphibian Archeria, or even Dimetrodon incisivus, a pre–Republic of Texas lizard with a nasty personality and spikes on his back. But he spawned plenty of other peculiar creatures slinking along the cracked sidewalks and sunbaked lawn surrounding Archer City’s courthouse. “Sonny had watched the two shoot so many times that it held no interest for him, so he took his week’s wages and walked across the dark courthouse lawn to the picture show.”

* * *

I remember my first trip to Archer City, about twelve years ago. There was the courthouse, the Spur Hotel, the Royal Theater movie house, the old jail, even the blinking stoplight in the middle of town. All the world’s a stage, I thought to myself, quoting from Shakespeare, and so it was in Archer City. As I walked late at night through these streets, it seemed to me that the characters from Larry’s books and films had just recently departed. The props had been left standing, unchanged by time.

Larry wrote about how the stage had been set. Take Archer’s museum, for instance. “The museum is housed in the old jail, and the county history was written by my lifelong neighbor Jack Loftin, who long ago took it upon himself to establish historical markers at spots about the county where notable events had occurred.”

With a broad brush, Larry described the museum’s prize artifacts, including “a few ancient tractors, a gas pump, various fragments of oil field equipment, a few harrows, my grandfather’s last saddle, and a few well-rusted tools, all of which would have been seized by the garage-salers had they materialized a few years earlier.”

Another artifact of sorts is the Spur Hotel. It opened in 1929, just in time for the stock market to crash, which wiped out its first board of directors, and turned the place, or at least the bottom floor, alternately into a shoe store, a domino parlor, and a newspaper office. Abby Abernathy and his sister renovated the hotel in 1990.

Abby is credited with shooting the bobcat that snarls by the fireplace and Mitch Green shot the elk whose head hangs nearby. One travel website describes the Spur as a “boutique hotel.” Another notes that travelers must find their room keys themselves, behind the reception desk. A third mentions that the Spur is NOT “within 15 miles of a beach.” Well, of course not. Nor is it fifteen miles from any “Major Pilgrimage Place.” But that’s misleading, because within fifteen miles is Archer City’s sweetest cathedral, the Dairy Queen.

It was in the late 1960s, Larry explains, that Dairy Queens began to appear in “the arid little towns of West Texas,” and they performed an essential function: “Certainly, if there were places in west Texas where stories might sometimes be told, those places would be the local Dairy Queens: clean, well-lighted places open commonly from 6 a.m. until ten at night.”

The Archer City Dairy Queen combined the functions of a tavern, café, and general store:

The oilmen would be there at six in the morning; the courthouse crowd would show up about ten; cowboys would stop for lunch or a midafternoon respite; roughnecks would jump out of their trucks or pickups to snatch a cheeseburger as their schedules allowed; and the women of the villages might appear at any time, often merely to sit and mingle for a few minutes; they might smoke, sip, touch themselves up, have a cup of coffee or a glass of iced tea, sample the gossip of the moment, and leave.

Larry noted that local gossip soon goes stale—and so regular attendance is necessary: “Most local scandals were flogged to death within a day or two; only the steamiest goings-on could hold the community’s attention for as long as a week.”

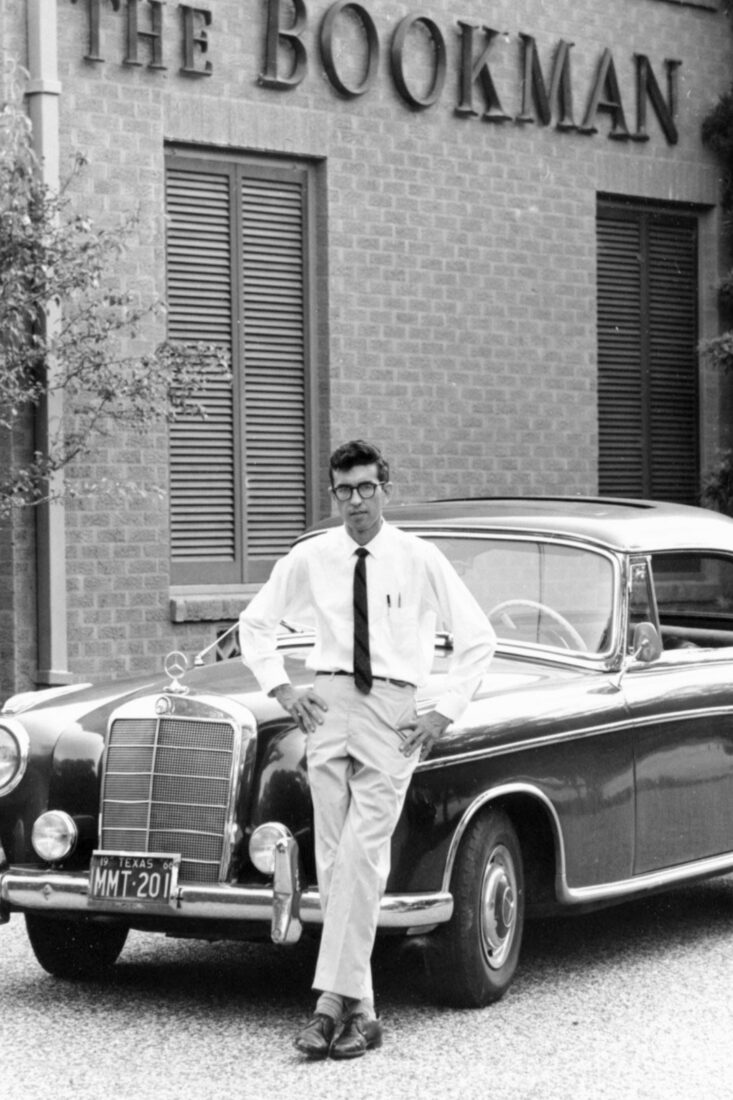

Last, and most important, is the movie house. Larry’s attention to the theater seems to have been piqued by a personal experience: Larry’s father went to Wichita Falls in 1917 to see his first film. It was a comedy, Larry wrote, and his father had to be carried out of the theater, he was laughing so hard.

The Archer City theater depicted in The Last Picture Show had Storm Warning on its marquee that summer night in the 1950s, along with posters announcing films by Doris Day, Ronald Reagan, Steve Cochran, and Ginger Rogers. Finally, the characters strolled onto the stage.

“It was past 10 p.m.,” Larry wrote in The Last Picture Show, “and Miss Mosey, who sold tickets, had already closed the window; Sonny found her in the lobby cleaning out the popcorn machine. She was a thin little old lady with such bad eyesight and hearing that she sometimes had to walk halfway down the aisle to tell whether the comedy or the newsreel was on.”

The connection between Larry’s novel and the real Archer City became even more obvious when the film was made. “A little more than half a century after my father saw that pie thrower,” Larry wrote, “a movie company arrived in Archer City to film a novel of mine called The Last Picture Show.”

All the set pieces were there, in living black-and-white: the Spur, the corner gas station, the courthouse on the square, the old county jail. And now there were Ben Johnson, Cloris Leachman, and Cybill Shepherd coming along the streets. It was a far cry from Dimetrodon incisivus dragging his tail around town.

The Last Picture Show wasn’t the last film to use the streets as its stage. There came the sequel, Texasville, and then a documentary about the making of both films. “That made—in all—three movies and two novels set in the same small Texas town, adding onion-like layers of fiction to what was already the somewhat complex facts,” Larry noted.

* * *

One of the most salient characteristics of Larry’s fiction is his representation of the land of West Texas as hard and unforgiving. It was a lonely land too. Larry said that the only beauty in his birthplace could be found by looking into the sky. “One of the things I’ve been doing,” he once wrote, “is filling that same emptiness, peopling it.” These weren’t imagined characters. “They were the real people, living their lives, unaware that it might be one day reflected in art.”

Plopping real people into his novels and screenplays, Larry acknowledged in a book-length, semi-autobiographical essay written in Archer City, Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen, caused some problems. “The townspeople at times seemed understandably confused, as parts of their own lives leaked into the film and parts of the film leaked back into their lives . . . as time went on it became harder and harder to say where fiction started or fact left off.”

Yet Larry seemed surprised that in using real characters from the town he created more than a few cases of mistaken identity. “I recently learned to my amazement that several impeccable matronly local women now think that they were the model for Charlene, the gum-chewing teenager who hangs her bra from the pickup’s rearview mirror in The Last Picture Show.”

Understandably, Larry didn’t go out of his way to point out to his publicists or reviewers that The Last Picture Show was based on Archer City. He called the fictional town Thalia, in fact, and the copyright page declares, “This book is a work of fiction. . . . Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.”

But anyone within a hundred miles knew it was Archer. After all, Archer City is a thirty-minute drive from Wichita Falls, just as Thalia is in the book. And Archer has a single stoplight in town. And a museum and a café. Sure, a few other Texas towns have that. But what other town is thirty minutes from Wichita Falls and has a picture house right across the street from the county courthouse? None. The clincher came when Larry confessed in print: “The Last Picture Show is lovingly dedicated to my hometown.”

* * *

Many Americans live in towns that have changed dramatically over the last few years, with layer upon layer of commercial sediment settling on top of what was once there. Take Orlando: Once there were orange groves and modest mom-and-pop stores. Now chain restaurants, souvenir shops, condos, and shopping centers have buried the original place beyond recognition. Austin, Texas, is going through the same process. It’s even happening in Charleston, South Carolina.

But Archer City is less today than it was in 1966 when Larry’s novel was released, and less than when the movie was filmed. Gone is the Goodyear tire store, the Cole-Ellis appliance store, McWhorter’s Food, and Holder’s Jewelry. Gone is the movie theater. It’s a starker place than it was. This decline in the economy is of no comfort to the citizens here. The shuttered buildings spark fear and anxiety among residents that Archer City could someday crumble into the prairie like so many other small towns surrounding it.

But to an out-of-town writer attempting to adopt Larry’s gift for peeling back the layers of history, the empty buildings and the bleached dinosaur bones scattered beneath the prairie around Archer County make a dramatic impression. They leave this author thinking about the characters who walked the streets before me, whose faded photographs found a place on the walls of the historic Spur Hotel and in the minds of countless fans at the picture show.

Erik Calonius is the author of The Wanderer: The Last American Slave Ship and the Conspiracy That Set Its Sails. The book inspired the creation of a city museum that attracts visitors from around the world. He is a former reporter, editor, and London-based foreign correspondent for the Wall Street Journal and was the Miami bureau chief for Newsweek. He also served as an editor and writer for Fortune, where he was nominated for the National Magazine Award.

Excerpted from Pastures of the Empty Page: Fellow Writers on the Life and Legacy of Larry McMurtry, edited by George Getschow, © 2023, published with permission from the University of Texas Press.