The intersection of the rarefied world of fine art, with its gallery exhibitions and Chablis-sipping collectors, and the down-home world of country music, with its honky-tonk shows and Lone Starswigging boot-scooters, can be boiled down to two words: Terry Allen.

The fine-art world has long renowned Allen for his multidimensional assemblages of drawings, lithographs, and sculptures that he often laced with elements drawn from his West Texas boyhood. Major museums—among them, New York’s Museum of Modern Art and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles—have his work in their permanent collections. In the country music world, he’s known for off-kilter, radio-unfriendly songs such as “Amarillo Highway (for Dave Hickey),” a Panhandle corker that’s been sung by Bobby Bare, Robert Earl Keen, and, more recently, Sturgill Simpson. (Among the other artists who have recorded Allen’s songs: Lucinda Williams, Guy Clark, and David Byrne.) He’s put out a dozen records since 1975, including the seminal concept album Juarez, and two years ago, at age seventy-eight, he headlined an Austin City Limits episode.

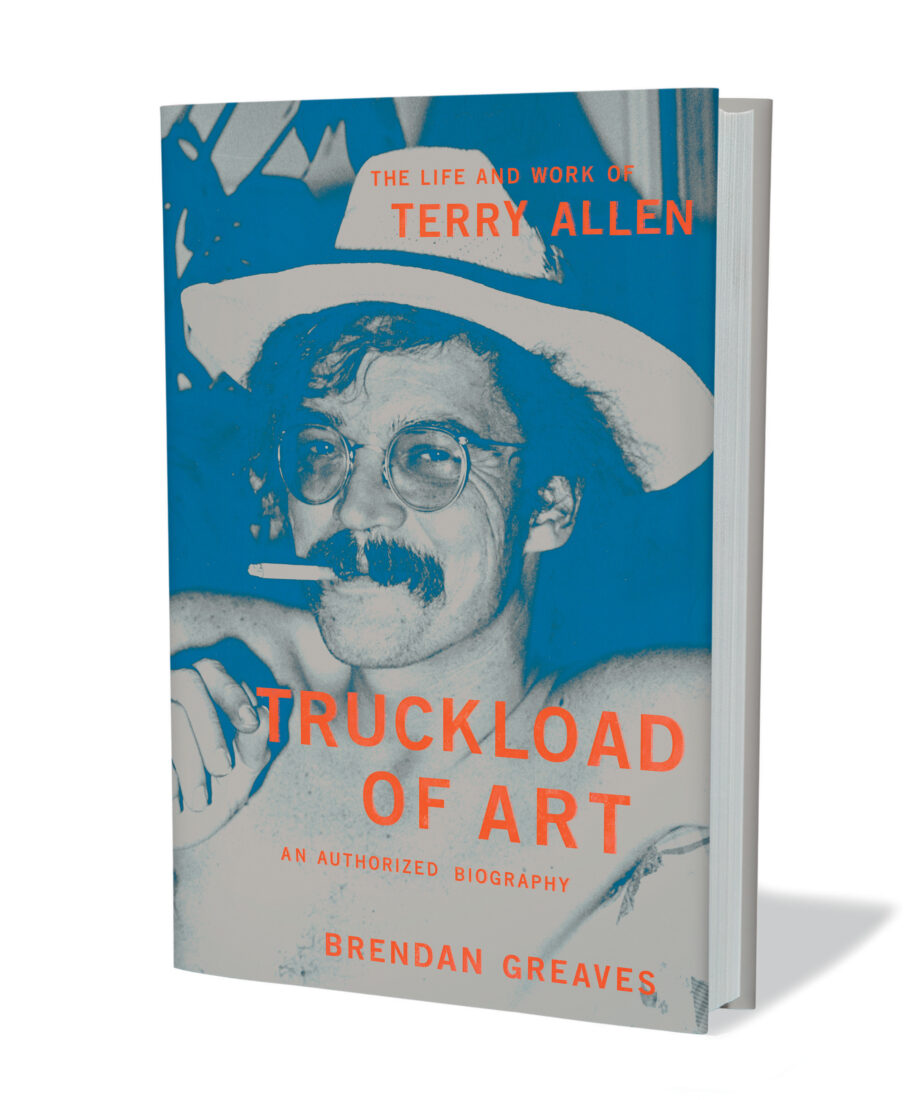

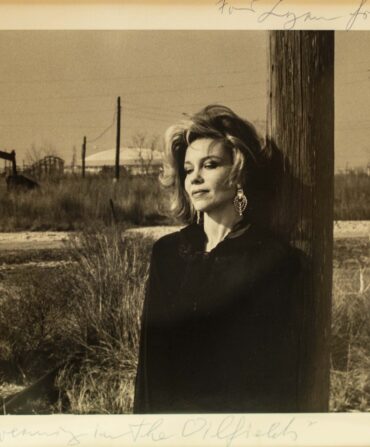

The origins of Allen’s artistic ambidexterity—although omnidexterity might be a better term, considering his forays into theater, prose, and even cinema (that’s Allen playing Uncle Jim in Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon)—trace back to Lubbock, Texas, as Brendan Greaves reveals in his intimate new authorized biography, Truckload of Art. Allen’s dad was a pro baseball player turned wrestling and concert promoter; Mom was a barrelhouse piano player turned cosmetician. Hybrid lives, then, were nothing alien to him. Neither was hybrid creativity. As a child, he’d sometimes hide in a bathroom stall during his father’s concerts, listening and drawing, “hearing that pounding music,” as he told Greaves, “and seeing those elaborate porno drawings on the bathroom walls.” He came to view “making music and making marks as the same kind of act.” At age sixteen, he scrawled down in a journal not one private ambition but rather three: “I want to be an artist. I want to be a writer. I want to be a musician.” He had no conception, Greaves writes, “that he could possibly be all three things or that all three things were in fact one thing.”

Italics mine, because that line, to me, conveys the unifying theory of Allen’s life and work, the essential koan. Art may be “the shortest distance between two question marks,” as Allen famously quipped, but it was also, for him, a means of escape. Dust-whipped Lubbock, on the flat Llano Estacado, felt to him like a dead end. (“Lubbock or Leave It,” as the Chicks song goes.) “If you were creative, you had to run as soon as you had the chance,” Allen has said. But just how you ran—armed with a paintbrush, a guitar, a pencil, or a camera—didn’t matter. You could draw yourself out, or sing yourself out, or, like Allen, do both (and more) at the same time. Years after he’d left, someone asked Allen for a definition of art. His reply: “To get out of town.”

Truckload of Art follows Allen in the 1960s from Lubbock to Los Angeles, where he studied at the Chouinard Art Institute (now California Institute of the Arts), made his musical TV debut on Shindig!, and brushed uncomfortably close to the Manson family murders. (Befitting Allen’s distinction-blurred life, the cameos in Truckload of Art range from Byrne to Tommy Lee Jones to Christopher B. Stubblefield of Stubb’s Bar-B-Q fame to Cormac McCarthy.) But Greaves also follows Allen back to Lubbock, where, in 1970, he began work on what would become his groundbreaking assemblage of songs, prints, and drawings, Juarez, and, in 1978, he recorded his other seminal album, Lubbock (on Everything), a rangy song cycle that’s been likened to Robert Altman’s Nashville. Allen made peace, on that album, with where he was from—with the concept of rootedness he’d long tried scorning. “You can either reconcile with that happy and horrid fact,” as Greaves writes, “or continue to wriggle strenuously away.”

“Talking about art,” as Allen once said, may be “trying to French kiss over the telephone,” but Greaves does an admirable job describing the ecumenical contexts and nuances of what are often indescribable works. But he does an even grander job, with clear but measured affection, getting onto the page the contexts and nuances of Terry Allen, an utterly unique figure at the crossroads—or maybe better, the eight-way interchange—of American art, however you define it.

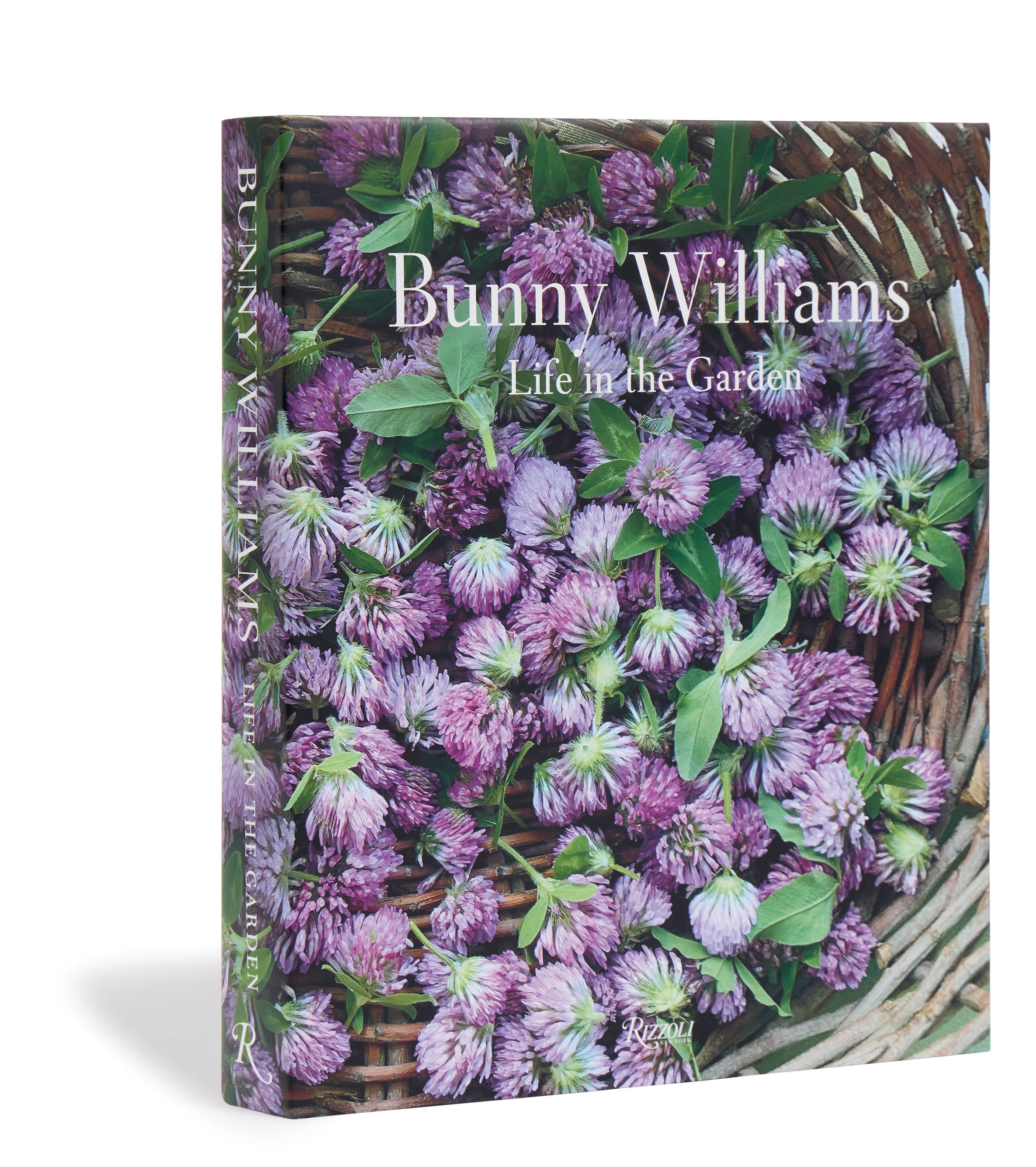

More New Reads: Bunny in Bloom

Garden elegance and ideas from a design legend

Bunny Williams’s first garden memories are dusted with her native Virginia’s red-clay soil. Even now, for the internationally known interior designer and tastemaker, nature remains her creative touchstone. Throughout her personal and beautiful new botanical memoir, Life in the Garden (Rizzoli), Williams digs into her love of plants, sharing outdoor hosting tips, design sketches, and photographs of her own garden through the seasons. She holds equal reverence for an unruly field of Queen Anne’s lace and an artfully arranged centerpiece of ivy, zinnias, or orchids. Floral arranging, Williams says, is “like painting a picture without the pressure. Flowers are already perfect.”—CJ Lotz Diego

Garden & Gun has an affiliate partnership with bookshop.org and may receive a portion of sales when a reader clicks to buy a book. All books are independently selected by the G&G editorial team.