My mom called me last week to tell me about the latest visit from her parents in the form of a cardinal. Every time she showed up for an appointment at the cancer institute in Spartanburg, South Carolina, a single red bird would greet her in the branches above the parking lot. “They say cardinals are people that have passed on,” she explained. “I see my mom and dad every time.”

What does a nameless yellow bird mean?

The day after she called me, I received a visitor of my own—one that looked to be a long, long way from home. With feathers the color of mango flesh and gray wings streaked with white, he stuck out like a mythical creature from the branches of the water oak in my yard in Charleston. As a twenty-four-year-old “old soul” who spends her mornings listening to Northern cardinals whistle birdie, birdie, birdie and watching the tiny gray chickadees and dusty-brown sparrows hop around my feeders, I knew the newcomer was special. I texted a photo to my mom, who had absolutely no idea what the species was, but offered up a prophetic reading of its energy anyway: That bird is a sign of beauty and peace.

Given my age, people are always surprised to learn how obsessed I am with birdwatching. It’s been my daily meditation for a few years now, but I’ve loved the practice since I was little. Listening, observing, and taking note are at the heart of birding—perfect for a painfully introverted kid who was happiest exploring the woods alone. But for me, it isn’t necessarily a solitary activity. I’ll never forget my first time kneeling in the woods in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, accompanied by my college printmaking professor, who’d noticed me staring at the red-shouldered hawks circling outside our studio window. Squinting through binoculars she’d planted in my hands, I watched a larger-than-life pileated woodpecker drill into a snag and a goldfinch roll around in the creek and shake water from its yellow head.

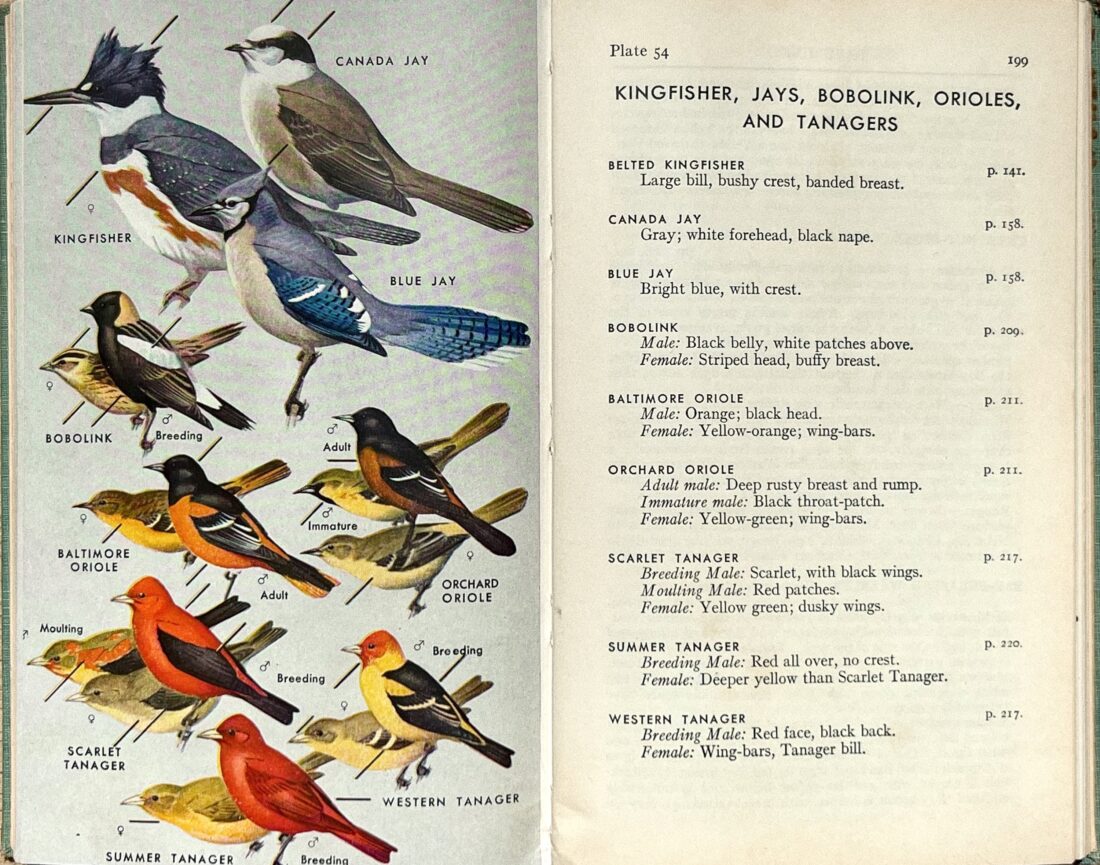

Those early birding lessons didn’t prepare me for my sunshine-colored visitor in Charleston. My Merlin Bird ID app, which always picked up the faintest of cries from far-away red-tailed hawks, couldn’t help me with my silent new friend. He was too big to be a yellow-bellied warbler, and his sharp orange beak didn’t match the stubby gray one of a lesser goldfinch. I managed a subpar iPhone photo through my binoculars and posted my first-ever message on the Charleston Bird Club Facebook group. “I’m thinking female Western tanager?” I suggested, afraid a wild misidentification would betray me as an idiot to the group of 2,700 members.

But to my nerdy glee, comments began trickling in: “Great sighting! Western tanager is correct,” one group admin said, and she encouraged me to log my sighting on the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s site, eBird. Even better, some commenters shared their own stories of Western tanager sightings and other unusual backyard visitors; one former Charleston resident cited their log of sooty and bridled terns, woodcocks, white-winged doves, and red-breasted nuthatches from the late seventies.

Western tanagers can be spotted all along the West Coast in conifer forests; they winter in Central America and fly north to the United States and Canada to forage, breed, and shelter in the canopies of open woodlands. Their typical range doesn’t even reach the eastern part of the Texas border. In Roger Tory Peterson’s A Field Guide to the Birds, Western tanagers are considered “an accidental”—and “the rarest of all rarities”—on the East Coast, though there’s a record of them from Maine to Louisiana. I didn’t fully appreciate this until I started to engage with the multitude of birders who showed up at my house in the days following my eBird report, which had apparently triggered some unseen magnetic force in the world of South Carolina avian enthusiasts.

The day after my report, I logged my first human encounter. I woke up and pushed my curtains open to see if the Western tanager was in the tree, but instead, I found a young man at the foot of my house. His name was Charles Donnelly, he ran his own small birding business, and he’d come to find the tanager himself. He’d only spotted three in more than a decade of birding in Charleston. Before leaving, he pressed the club’s card and an embroidered patch of a cedar waxwing into my hand. “Thank you for having me here,” he said.

Friday afternoon, my roommate, Sadie, and I paused from having lunch on our second-floor porch to peer down at two birders, who coincidentally showed up at the same time to seek out the tanager, which was perched contentedly in the canopy a few yards away from us. For a few minutes, we tried to help the two men locate the bird, but their view from below was too thick with leaves and branches. Somehow, I convinced Sadie to let me swing open the door for these complete strangers and invite them up to see the bird and snap some photographs. But even on the porch, with the four of us huddled together, the older of the two men had trouble spotting it. His frustration was palpable. Without hesitation, the younger birder stepped in and steadied his hand on the man’s, drawing a line of vision to the bird. The sudden burst of excitement made my heart do a happy dance. “Holy smokes,” he said, peering through the binoculars. “This is something special.”

What does a castaway Western tanager mean?

People kept trickling in over the next few days to stand under my tree and look for a bird they may or may not find. Beyond my one special tanager, my human visitors have included photographers, a former historic plantation gardener, and a “top ten” contributor to eBird in South Carolina, accompanied by his mother. I connected with Dennis Forsythe, an eighty-two-year-old retired Citadel ornithology professor who has been recording his bird sightings since he was six years old. After trying twice to locate the tanager in my yard, he finally spotted it, and he informed me that the bird was more likely a young male than a female. “This is the only one I know around this year,” he said. “His head has that touch of red.” Forsythe texted me a close-up photo. Sure enough, there was the faintest scarlet tinge, like the lick of a flame.

In meeting the kindred spirits who have flocked to my tree and tanager, the joy of my daily window-watching has become twofold. My friends and family are tickled by it all—me inviting strangers into my house, obsessing over a little bird. But one friend, who gifted me Mary Oliver’s Devotions and loves birds as much as I do, cried happy tears as I recounted the week’s events to her on a bench by the marsh, while clapper rails called out from their shelters of grass.

“It’s so sweet,” she said, wiping her cheeks.

The marvel of the tanager feels like it has fluttered from Oliver’s pages to my shady street corner. In her poem “This Morning,” she describes a group of people coming together to watch redbird eggs hatch: And just like that, like a simple / neighborhood event, a miracle / is taking place.

A Western tanager means community. I can’t help but celebrate being able to connect with so many others over something ordinary but spectacular, something both smaller and larger than us—a mysterious bird in an unexpected spot.

Garden & Gun has an affiliate partnership with bookshop.org and may receive a portion of sales when a reader clicks to buy a book.