For the opening party of Mariano’s Mexican Cuisine in Dallas, Mariano Martinez sent out invitations printed on corn tortillas. He ordered a dozen cabrito to roast and, short on cash, convinced a local distributor to donate a few cases of Champagne. Martinez’s restaurant opened on fumes for finances. He had been turned down by eleven banks, sold everything he owned, and secured a small SBA loan and funds from family and friends.

But he had flair, and plenty of it.

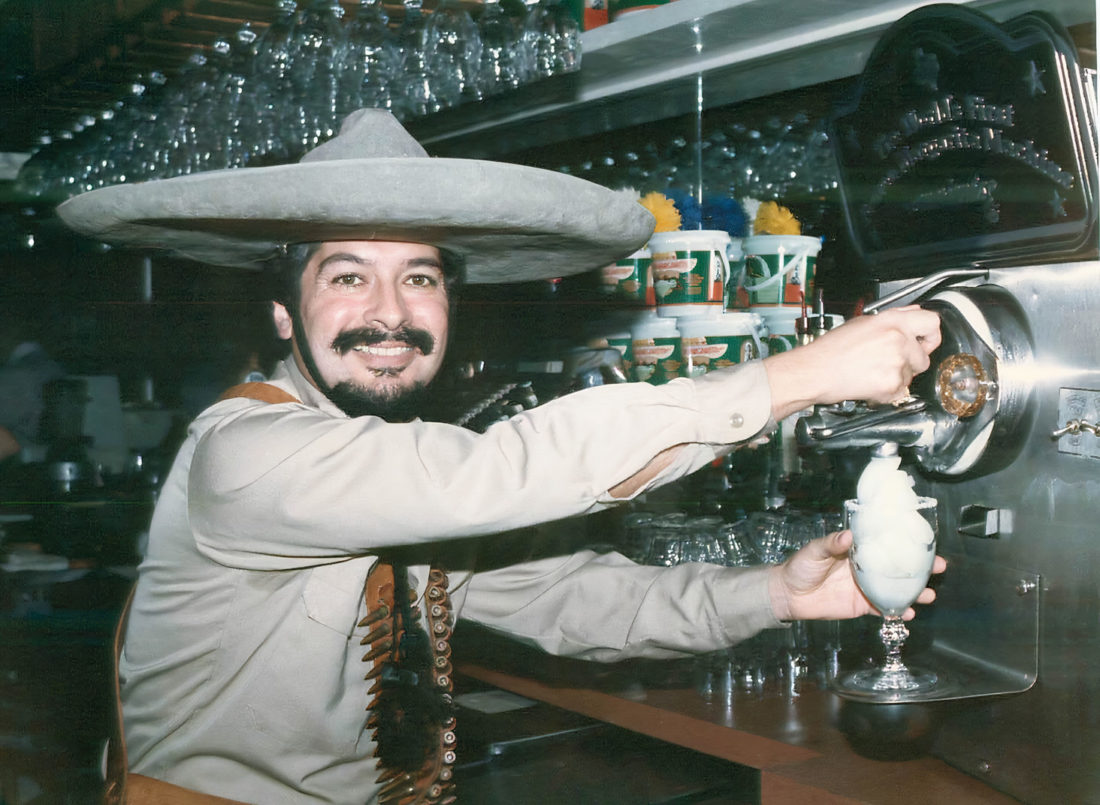

For his newspaper portrait, Martinez grew his hair long and sported a black mustache and goatee. “I put on a Mexican sombrero like Emiliano Zapata, with a bullet belt across my chest,” recalls Martinez, a Mexican American whose height and fighting weight at the time were five feet, six inches, and 120 pounds, respectively. “I dressed like a Mexican revolutionary hero. I felt like I was revolutionizing Mexican cuisine.”

Martinez wasn’t too far off the mark. On May 11, 1971, shortly after opening, he would change the course of global cocktail culture with the world’s first frozen margarita machine.

When Martinez was growing up, his father worked eighty hours a week in his Dallas restaurant, El Charro. “That wasn’t the life I wanted for myself,” says Martinez, who dropped out of high school in the tenth grade to pursue music and golf. He had above-average but not-quite-star-quality talent, and in the following years, Martinez watched from the sidelines as peers like singer Trinidad López and golfer Lee Trevino made it big. He returned to school for his GED and then earned a two-year degree from El Centro College, where an interests assessment directed him toward entrepreneurship. “This was during the Nixon era, at the time of the Vietnam War, when young people were burning the flag, burning their draft cards, and refusing to go to war,” Martinez says. “While hippies were calling everyone capitalist pigs, I wanted to go into business.”

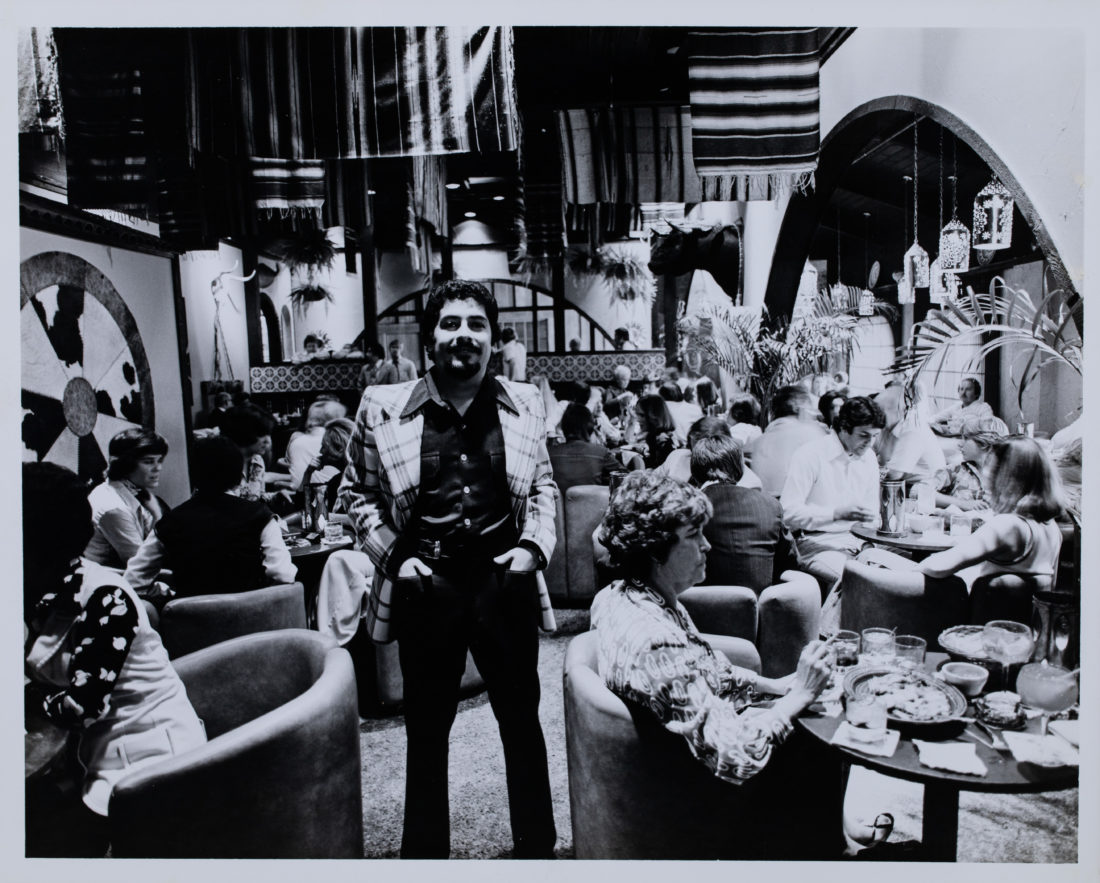

He found himself drawn back to restaurants. Martinez had long been captivated by La Tunisia, a Middle Eastern–themed spot in Dallas with a sheik’s tent cocktail lounge, costumed servers, and a seven-foot-tall doorman decked in a fez. “The minute you drove up, it felt like you had been to another place and time,” he says. “That’s when I got the idea of elevating Mexican food and making it into an escape experience.”

Mariano’s employed sorority women from nearby Southern Methodist University as greeters, and they dressed in big skirts and gaucho hats. Mexican music pulsed through the restaurant’s sound system, and, upon guests’ arrival, a host would invite them into a cantina for a frozen margarita. At first, those margaritas were concocted in blenders with a recipe—“high-dollar” tequila, Cointreau, lime juice, simple syrup, and ice—passed down from Martinez’s father, who had worked in a speakeasy in San Antonio’s Hotel Saint Anthony in 1938.

The margarita has many purported but no confirmed origins. There are creation myths involving barmen, actors, dancers, and singers on both sides of the border, but the drink is most likely a descendant of the classic daisy cocktail, just made with tequila instead of brandy. (Margarita means daisy in Spanish.) “My father does not lay claim to any one of those stories,” Martinez says. “All I know is that margaritas, and the frozen margarita, existed in 1938.”

Despite having a full bar and cocktail menu from which to choose, almost all of Mariano’s guests ordered frozen margaritas, and soon, he says, his bartenders and blenders were burning out. A customer pulled Martinez aside one night to tell him that the margaritas weren’t tasty, consistent, or even cold. “Every time we got an order, the bartender would take the lime, cut it in half, squeeze it into a blender, measure the Cointreau, add simple syrup, then ice, and turn on the blender. Then repeat,” he says. “That process works in a small speakeasy, where people are ordering different drinks. But we were selling 99 percent margaritas.”

The next morning, Martinez walked into a 7-Eleven for a cup of coffee and found the solution for his margarita conundrum: the Slurpee machine, whose technology was developed in the 1950s and licensed by the convenience store chain in 1965. “I thought with a Slurpee machine, I could make a big batch at the beginning of a shift, and the recipe would be consistent,” Martinez says.

The Slurpee machine didn’t exactly pan out. It was proprietary to 7-Eleven, and when Martinez finally spoke to someone at the company, “they asked me if I had taken chemistry in high school. ‘Don’t you know alcohol doesn’t freeze?’” Undeterred, he bought a used Saniserv soft-serve ice cream machine and worked with a friend to modify it. It took about ten days of tinkering, which “seemed like a lifetime” to Martinez, who couldn’t satisfy his patrons’ thirst for frozen margaritas quickly enough.

When he brought the machine back to Mariano’s, fellow operators warned Martinez against displaying it in his high-end cantina. “They told me, ‘No one is going to pay $1.25 for a margarita coming out of a machine. They want the romance of a beverage made right in front of them.’ But I had no place to hide it.” So he installed his revolutionary machine on the counter of Mariano’s, tweaked his father’s recipe to fill a five-gallon bucket, and started serving consistent, delicious, ice-cold frozen margaritas.

For about a year, Martinez owned the only frozen margarita machine in the world. The Dallas restaurant community was small, he says, and the Mexican restaurant community even smaller. No one had the gall to copy his margarita masterpiece, “until everybody else succumbed to the frozen machine.”

Martinez never applied for a margarita machine patent, and beyond driving restaurant sales, he hasn’t received anything more than public admiration (and a few bear hugs) for his invention. “I never dreamed that I invented anything,” Martinez says. “I took an old soft-serve ice cream maker, modified it, and started using it for another purpose. But I do believe this. It was godsend. All my ideas have come to me in a flash. I feel like all ideas are already out there in the world. You just have to be sensitive enough and quiet enough to tune into them.”

Fifty years later, the margarita is among the most popular cocktails in America, and tequila sales are so robust that there is now an agave shortage in Mexico. The commercial machines, which cost $1,000 to nearly $10,000, are ubiquitous in local Mexican and Tex-Mex restaurants, stadiums, airports, and catering operations. After Martinez advanced batched cocktails, chain restaurants—Chili’s, Olive Garden, Applebee’s, P.F. Chang’s, Texas Roadhouse, Fat Tuesday, Senor Frog’s, and Margaritaville among them—began to deliver consistent frozen drinks of every flavor and hue. With a global supply chain and fool-proof instructions, the Sunset Passion Colada tastes the same at Red Lobster Dallas as it does in Kuala Lumpur.

The machine also gave birth to drive-thru daiquiri culture in New Orleans and made the piña colada a resort mainstay. In recent years, craft bartenders have embraced Martinez’s invention for its fun factor and speed of service, bestowing their own machines with names like James Swirl Jones and Kathleen Turner. And during the pandemic, frozen drink machines helped struggling bars capture essential revenue by allowing them to make and sell high-quality to-go drinks without a ton of labor.

At seventy-six years old, Martinez lives quite comfortably, splitting time between Dallas and Pebble Beach, in California. In his later years, he developed and sold margarita buckets, and Mariano’s grew to six locations. His original Saniserv machine moved from Texas to Washington, D.C. in 2005, joining Tupperware, Julia Child’s kitchen, and a Krispy Kreme Ring King doughnut maker in a permanent Smithsonian exhibit on American food and drink. He gets regular calls from journalists, who’ve just discovered a cocktail legend lives among us. He answers their questions patiently and with color, until his wife of forty-eight years, Wanda Wade Martinez, calls him to lunch.

More about Margaritas in Dallas

Mariano’s is part of Dallas’ Margarita Mile, a collection of several of the best margarita bars and restaurants in the city. Visit the website for more.