Whether gifted or inherited, pearls mark milestones on my life’s journey. A tiny pearl bracelet on my christening. The sixteenth birthday cultured pearl choker. Wedding day baroque pearl earrings. After our son’s birth, I strung my mother’s and grandmother’s Mikimoto pearl necklaces into a single, hip-length strand. I call it my lifeline.

Recently my husband Bob and I achieved major milestones. I reached a big birthday, surpassing the age at which my mother died too young. Bob retired after a successful career in the hospitality industry. Three decades ago, he proposed to me on a dive trip in Guanaja, Honduras, and our wedding anniversary was on the horizon. (Pearls are the traditional gemstone gift to mark thirty years of marriage.) We thought French Polynesia, commonly called the Islands of Tahiti, was the perfect setting to celebrate it all.

The beauty of lustrous Tahitian black pearls is world-renowned. Not so well known is what I would come to learn over the course of our trip: Since the early 1960s, the cultured pearl industry has used the shells of freshwater mussels harvested from Mississippi River Basin waterways to culture black pearls. Southern freshwater mussel history is embedded in the very core of Tahiti’s precious gems.

Layers of culture and economic history

In the early 1900s, the Japanese farmer-inventor-businessman Kōkichi Mikimoto became a groundbreaker in the cultured pearl industry. He discovered that inserting smooth, round beads—called “nuclei”—of strong, hard Mississippi mussel shell into an oyster’s flesh stimulates the secretion of nacre, or mother of pearl. Nacre adheres firmly and evenly to these nuclei, which do not crack when drilled through to string pearls. These qualities, coupled with Mikimoto’s marketing savvy, created unprecedented international demand for Mississippi River Basin mussel shell.

In the 1980s and 1990s, while China and Japan fiercely competed for pearl industry dominance, commercial mussel harvest peaked in the Southeastern states of Tennessee, Arkansas, Kentucky, and Alabama. Don Hubbs, a freshwater mussel consultant for the Nature Conservancy, was the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency mussel coordinator during this “Shell Rush.” His 1995 report cites 7,761,235 pounds of freshwater mussels harvested; Tennessee accounted for 90 percent of the nation’s annual shelling exports.

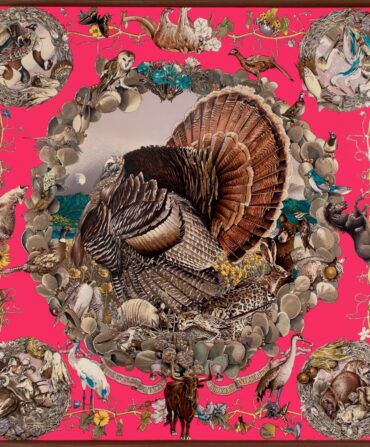

At the same time, black pearl cultivation surged in French Polynesia’s remote Tuamotu Archipelago and Gambier Islands. Endemic to this region, the Pinctada margaritifera oyster, or black-lip pearl oyster, is the world’s only oyster that produces black pearls, which are actually a myriad of colors.

Although mussel shell export has steadily tapered off since then, Southern shell exporters still ship to China and Japan as well as to the Pacific Islands and Australia. One of the largest suppliers to Chinese nuclei manufacturers, for example, is Tennessee’s American Shell. According to Eric Ganus, the commercial fishing and mussel coordinator for the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency, three-ridge, ebony, and washboard mussels harvested from Kentucky Lake account for most of the state’s shell exports.

Korean and Chinese production of such shell material has surged in recent years, though. “Originally, starting in the 1960s, the Japanese provided us with nuclei made of mussel shells from Mississippi River waterways,” says Richard Wan, commercial director for the retail operation of Robert Wan, the world’s leading producer of cultured black pearls. “Today, we buy nuclei from Korean and Chinese producers that raise the exact same species of mussels as those harvested during Mikimoto’s time.”

Diving into Tahitian pearl farming

In the Tuamotu Archipelago’s largest atoll, windswept Rangiroa, we dove with lemon sharks and bottlenose dolphins in Tiputa Pass. Our dive outfitter, the 6 Passengers, and Hotel Kia Ora Resort & Spa are located near Gauguin’s Pearl farm and shop. Here, Tahitian biologist Dr. Philippe Cabral leads free tours of his family’s enterprise. “Black pearls are truly our product, which you cannot find in many other countries,” Cabral told us. “We easily produce 90 percent of black pearls for the international cultured pearl market.”

Seated in the shade of a thatch-roofed pergola, Cabral told us about Pinctada margaritifera oysters, his tools spread before us as he explained pearl farming basics in French, then English. It goes like this: Oysters grow in mesh bags suspended on lines in lagoons. In each oyster, grafters insert a nuclei and piece of live Pinctada margaritifera mantle tissue, which contains the DNA that dictates pearl color. “Because the quality is better, we choose to buy United States’ Mississippi River mussel shell nuclei,” Cabral said, “even though it’s more expensive than nuclei made from shell harvested in China.” A grading scale assessing its shape, size, surface quality luster, nacre thickness, and color determines a pearl’s market value.

On the next part of our adventure, we took Windstar cruise to Ra’iatea in the Society Islands Archipelago. Between exhilarating morning drift dives floating in currents through crowds of tropical fish and blacktip sharks, we joined guided shore excursions to pearl farms and ancient, open-air temples called maraes. Marae archeological artifacts, some dating back more than two thousand years, include oyster shell fishing hooks, tools, weapons, and adornments.

Marae Taputapuātea, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, preserves ancient Polynesian history and culture. The black, volcanic rock complex’s main temple is dedicated to ‘Oro, god of war and peace. ‘Oro gave his human lovers pearls and gifted the Polynesian people the first pearl oysters, the legend goes. Tāne, god of the forest, harmony, and beauty, illuminated the night with glowing pearls.

I soaked it all in. Under the full moon’s pearlescent light, I thought about the legends that imbue black pearls with the powers of strength, resilience, healing, protection, and love. They possess mana, a life force Tahitians believe pulses in all people, places, and things of the natural world, and that connects us all through space and time.

Pearl farms aplenty

Our next stop on Ra’iatea, Vairua Perles opened in 1994. Vai Brodien, thirty-five, is the grafter on her family farm, which produces twenty thousand black pearls annually. In twenty seconds flat, she removed a pearl and replaced it with a piece of black-lip pearl oyster mantle and a Mississippi River Basin mussel shell nuclei manufactured in Japan. In a day, Brodien performs the “delicate surgery” on four hundred Pinctada margaritifera oysters. “Harvesting the pearl is a magical moment because each one’s color is different,” she said. “A gold, silver, pink, blue, and ooooh my favorite, green!”

During its lifetime, a farmed oyster will produce up to three pearls before it is retired. Brodien and her mother make a delicious stew of retired oysters’ meat and craft jewelry from the shells, just like their ancestors did.

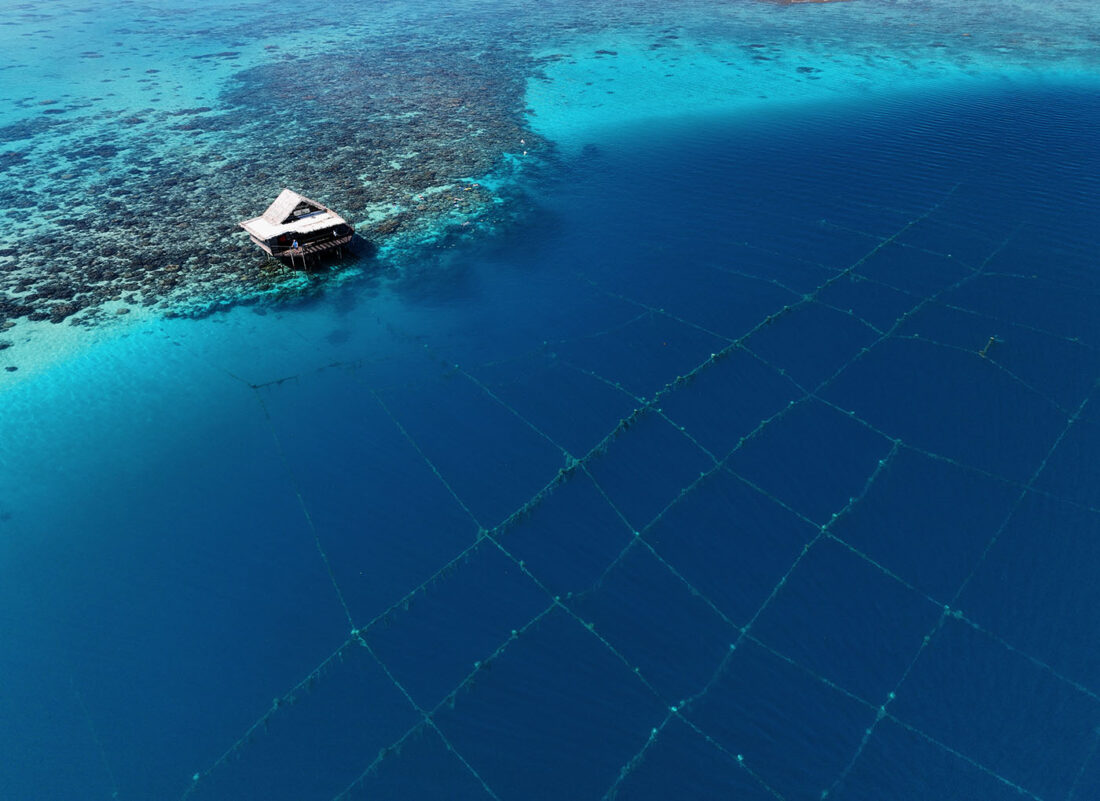

On the other side of the island, at Anapa Pearl Farm’s turquoise lagoon, Bob and I dove for our own treasures. A skiff whisked us to a thatched-roof, stilt bungalow overlooking coral gardens and a deep lagoon where pearl beds flourish, private yachts moor, and manta rays dwell.

The co-owners of Anapa Pearls, Lara Murray-Blanc, an American expat, and her French husband, Philippe Blanc, started their black pearl farm in 1997. They still rely on sustainable farming techniques: Reef fish clean algae off oysters’ shells (versus pressure washing). And grafters implant nuclei made of the farm’s retired oysters’ shells. “We employ and train only Polynesian grafters,” Lara said, “because it is best for the local economy that Polynesians are in control of their own product.”

Snorkeling in the sun-speckled shallows, I scanned the coral garden for oysters. Neon-colored, fluorescent parrotfish and brilliant yellow, white, and black striped sergeant major fish darted around knobby coral heads.

Spotting a salad plate–sized oyster about twelve feet down, I took a big gulp of air, kicked hard underwater, and reached for it. Of the three pearls we harvested that day, Bob surfaced with the real treasure. “Kit, this is for you,” he told me as he dropped it in my hands. “Happy thirtieth anniversary.” It was a Grade A, 11.5-millimeter, perfectly round, iridescent, titanium-colored Tahitian black pearl.